Bustling metropolis: too expensive. Bucolic countryside: too sparse. Middle-class suburb: just right.

When it comes to off-campus housing alternatives, the city of Evanston is about as good as it gets — an ideal combination of location and cost.

Northwestern students seem to have this figured out, as 60 percent of the total undergraduate population currently lives off-campus.

The recent announcement that students will be required to live on-campus for both their freshman and sophomore years beginning fall 2017 will therefore produce a considerable shift in campus culture. The school will go from having 40 percent of its sophomores take a pass on Northwestern-sponsored housing, to having 100 percent live either in residence halls or greek houses.

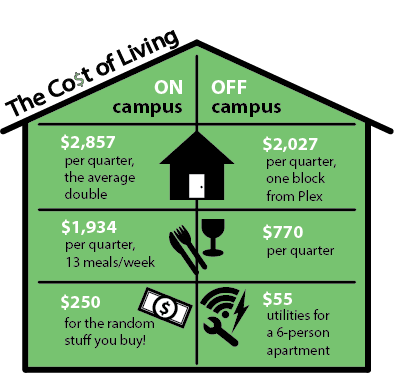

Residential services maintains that increasing opportunities for engaging with the student body is their primary incentive for the shift, but the requirement has the potential to severely limit those students who point to financial flexibility as their primary incentive for moving off-campus.

For low-income students who receive a refund equal to what on-campus housing and dining would cost, this requirement could be particularly harmful.

“It eliminates choice for low-income students and students in general,” McCormick junior Steffany Bahamon said. Bahamon is the president of the Quest Scholars Network – one cohort of students who are guaranteed to have their housing costs covered or refunded by the school.

While the average cost for a meal in a dining hall is around $12, Bahamon said her grocery bill is rarely more than $60 a week.

Weinberg sophomore Ava Armacost has had a similar experience living off-campus, not only with food expenses but also when first signing her lease.

“You’re able to find the price of an apartment or a house that you’d be willing to pay,” she said, explaining how she was able to shop around rather than accepting the limited menu of options offered by residential services.

Microeconomics professor Scott Ogawa reinforced Armacost’s observation. “Evanston is right at that sweet spot where it’s not cheap but it’s not expensive and there are a variety of options,” he said.

“The way places like NYU and Stanford work, they don’t require [housing], they promise it, and oh my goodness every last bed is taken.”

When asked how the university would reconcile the fact that many students feel it is cheaper to live off-campus, residential services’ executive director, Paul Riel, appeared unwilling to acknowledge the reappropriation of housing refunds.

“The university for the most part covers expenses – I just think that’s a fair way of looking at it,” he said.

The question at the crux of the financial issue is whether the University is taking a net-profit or a net-loss on every student who chooses to stay on campus.

“This two-year live-on requirement isn’t a financial thing for us – it’s not a way to make money – it’s an idea around whether we can deliver the undergraduate experience residentially,” Riel said. A logical case could be made, however, that the school wants to make sure that as many rooms as possible are occupied.

“It’s better for their bottom line to have every bed filled, and that’s presumably going to make it cheaper for everyone else,” Ogawa said.

A shift in the way on-campus costs are broken down could help to ameliorate some of the financial burden and give students more choice over how much they spend on housing, according to Riel.

Riel also explained how the housing office has in the past year changed their rate structure from 21 rental rates to down to seven. “Essentially what you’re able to do is look at what you can afford by tier and then see what buildings are available.”

Putting aside what some students see as negative financial implications, there are some exciting upsides to the requirement, according to Riel.

“If you’ve noticed the construction work that we’ve been trying to do, it’s all about creating new spaces,” Riel said. “This is a campus where 10 months out of the year the weather is pretty crappy, but our spaces are [currently] such that it’s pretty difficult to want to stay in a building because they’re uncomfortable."

The overarching idea, to be accomplished over the next 10 years, is for residential buildings to exist in “pods” – with Shepard, Allison, and 1838 Chicago (formerly home to Public Affairs Residential College) serving as the first example.

Between the three buildings, collaborative spaces, tutorial spaces, assembly spaces, a demonstration kitchen, a meditation room and a fitness center will be provided for students.

The university is also giving thought to the idea of delivering services, such as career advising and CAPS, residentially.

Besides quality-of-life perks, one reason that the two-year requirement is being implemented is to give the administration a way to maintain connections with students for a longer time.

“We’re working around this idea of...a stronger relationship to the university itself. A way that we can deliver what we think to be the experience that students...should have as members of the Northwestern community,” Riel said.