Maybe it was the regrettable decision to read Forbes’ list of majors with the highest starting salaries. Or maybe it was being asked by well-meaning friends and relatives what I wanted to do with my life and overcompensating by saying, “I can do anything I want with this!” while secretly meaning, “I have no idea what I want to do with this.”

At first, I thought my doubts about majoring in Social Policy and English were a result of too much opportunity – of academic FOMO, if you will. After all, I transferred to Northwestern this year specifically for SESP after a year spent complaining about “the inability to do what I love” elsewhere.

But this winter, I decided to try an introductory journalism class. While writing news briefs and interviewing strangers, I realized I was more interested in journalism than I was in education. Leading me to transfer. Again. Into Medill.

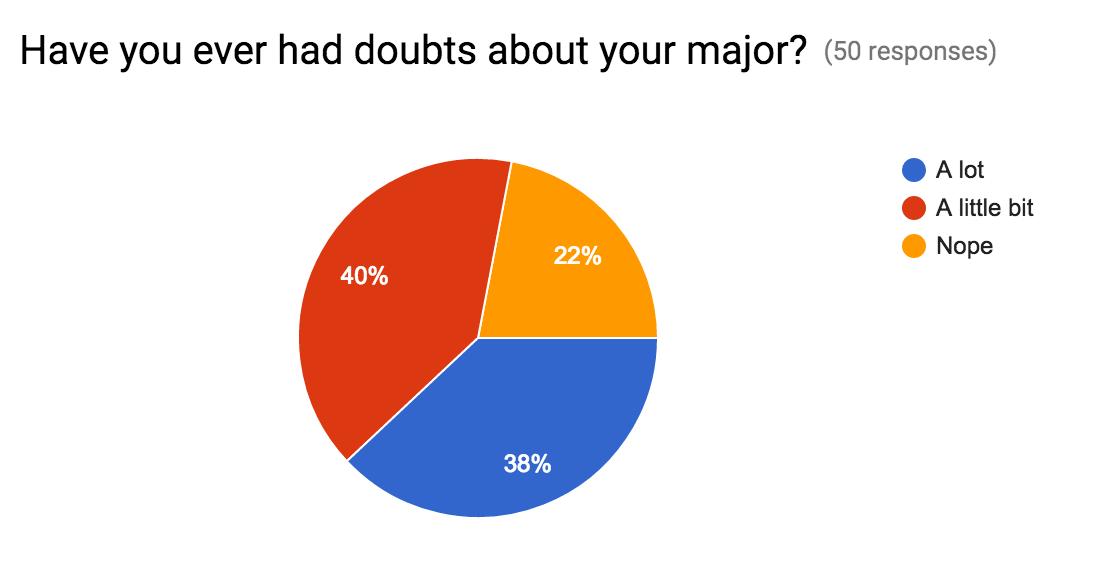

I felt like the world’s most indecisive college student at the time, but some highly un-scientific data suggests I’m not alone. A Whatsgoodly poll showed that 52 percent of the 295 Northwestern students who responded had “seriously doubted” their major, with a near equal breakdown between humanities/social sciences students and math/science students. What’s more, 19 out of the of 50 people who answered an informal Google Form expressed “a lot of doubt” about their major.

Deciding on a field of study isn’t as straightforward as the drop-down box on Northwestern’s application would lead students to believe. For some, the option to “select your proposed major” is itself the start of a slew of unintended problems.

“I thought the box was just to indicate what you were interested in,” Weinberg sophomore Natalie Burg said. Burg came into Northwestern as a declared chemical engineering major and switched to a political science major her sophomore year.

Northwestern’s policy to ask students what they plan to study even before they arrive on campus can make freshmen feel that they should already know exactly what they want to study without ever having taken a college-level course. Exploring is not encouraged, Weinberg freshman Lydia Wuorinen said. She entered Northwestern undeclared and believes taking classes that don’t count towards one specific major can seem like a waste of time.

“When it comes down to it, it does hurt you to explore,” said Wuorinen, who recently decided to declare a neuroscience major. “Looking back on it, it’s a year of classes I can’t get back.”

Some who enter college with a set idea of what they want to do, only to decide to change, think about “wasted” class time in a different way. When Weinberg sophomore Lucas Vieira decided to drop his economics major halfway through his sophomore year, his only regret was not focusing on political science sooner.

“I realized that I wouldn’t be able to study what I wanted to if I waited any longer, because I was just killing classes that I would need for my other major,” Viera said.

The mantra to “follow your passion,” though it sounds nice, can create even more problems for those who may not know what it is that they’re truly interested in, or need some more time to figure it out.

“It is true that really successful people – whether it’s financially successful or just sort of life fulfillment – have some sort of passion. So adults tell students to follow their passions,” microeconomics professor Scott Ogawa said. “But I don’t think that all students have passions. And is it okay to be like, 'I don’t know what my passion is?'”

Especially when the idea of having unbridled excitement for a particular subject seems more like a fallacy that an achievable reality, external validation can be enough of a motivator to study a particular major. After all, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to make a comfortable living and giving parents (who are often paying for college, or at least helping) the comfort of knowing that they will one day be financially independent.

“They wanted me to have job security, and it seemed like economics would have provided that,” Viera said. “It seemed like the safe thing to do.”

Burg said she was “pretty miserable” in her engineering classes her freshman year and felt jealous of friends who majored in the social sciences. But her parents’ pride at having a daughter studying engineering at Northwestern made her hesitant to switch majors.

“My dad would send me links every day about why engineering is the best major and leads to the best jobs,” she said.

An international student from India, who wished to remain anonymous to protect her privacy, initially planned to study psychology at Northwestern. But after her parents repeatedly warned her that she would be deported if she didn’t get a job upon graduation, she decided to switch to the learning and organizational change major in SESP.

“I’m only doing my major because I know it will get me a job,” she said.

The social status conferred by certain majors is another reason students can be hesitant to switch out of a major they may not even enjoy.

“My pet hypothesis is that large salary majors are a proxy for exclusive majors – high social status majors – and students like that,” Ogawa said. “It’s not the high income, per say. It’s that they’re doing something that’s considered an ‘achievement.’”

Admiration from peers and parents can validate students’ career choices more than just the salary they earn, Ogawa explained.

Despite admitting that she felt jealous of friends with majors in Weinberg all throughout her freshman year, Burg only realized that she needed to make a change when she finally took a political science class during her freshman Spring Quarter.

“I enjoyed going to class, which is something that had never happened before,” she said.

Despite a perception – and, likely, a reality – that one major is less lucrative than another, deciding on a field of study is about more than money.

“There are obviously going to be some adjustments as far as what I expect to make salary-wise,” Viera said. “I’m not going to be a billionaire, probably – not that I was going to be originally – but, you know.”

Ultimately, students find their passion, they become less preoccupied with the pursuit of status. Those who treat different classes, internships and club positions as mere stepping stones to a specific position are, unsurprisingly, ultimately less happy.

“The fear of regretting college was bigger than the fear of disappointing my parents or myself,” Burg said.