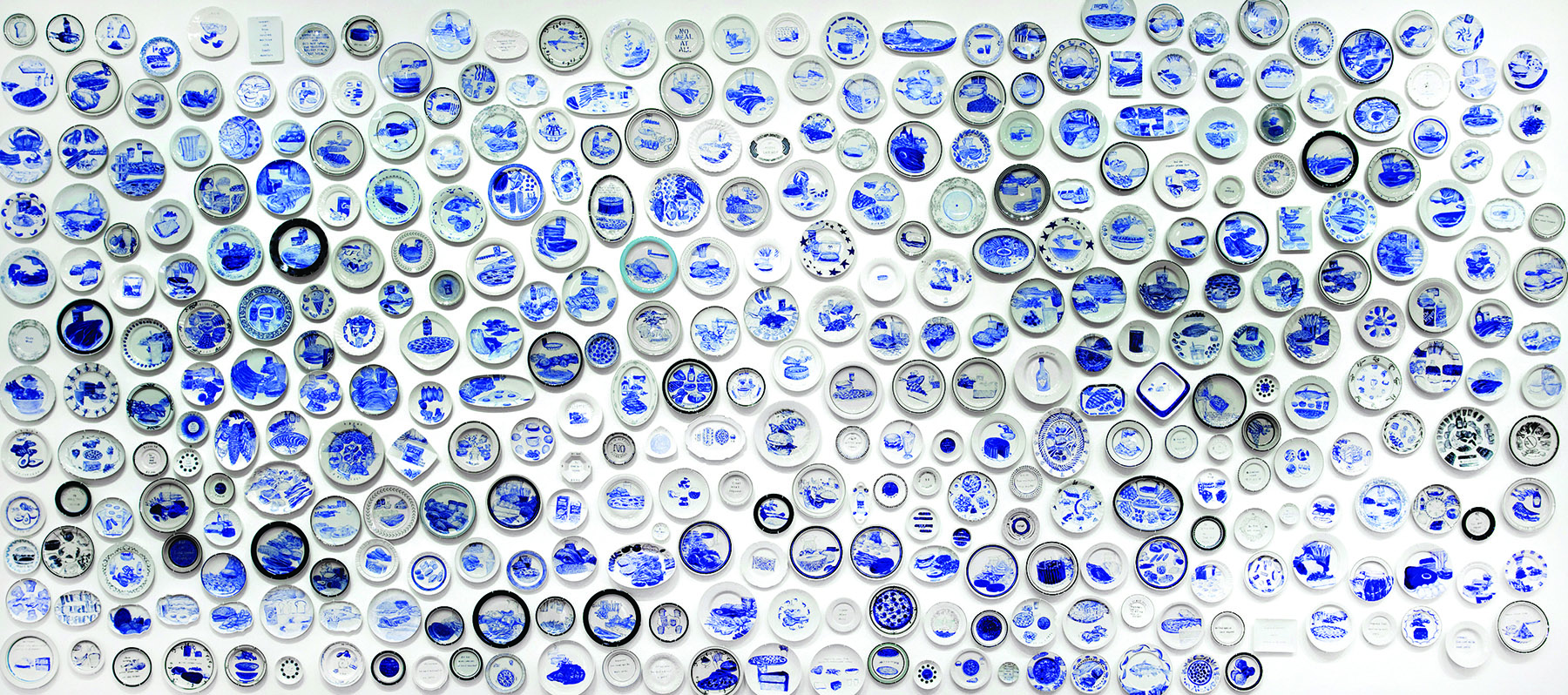

On May 9, the Mary and Leigh Block Museum debuted its newest exhibit, but no canvases adorned with watercolors or oil pastels lined the gallery walls. Instead, patrons found ceramic plates painted by contemporary artist Julie Green in her exhibition, “The Last Supper: 600 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates.”

Each plate tells a different story with its illustration of a last meal request from an inmate on death row. The exhibit, which runs through August 9, is meant to encourage thoughtful discussion about the use of capital punishment in the United States.

“What we really would like to do is take a show that is very directing and confrontational, and provide a physical space – the gallery – but also a kind of intellectual space where people can confront this issue head-on,” the Block Museum’s Curator of Special Projects Elliot Reichert said.

The meals are depicted in cobalt blue against a white ceramic plate and are accompanied by a description of the inmate’s last meal request, the date and the state where the execution took place. However, Green chose not to include any more details about the inmates or the crimes they were convicted of. She wanted to emphasize the humanity of the inmates by depicting their meals.

“Painting can be a meditation, a time to reflect,” Green said. “The meals are so personal, and, for me, they humanize death row.”

The project began in 1998, when Green read an article about a final meal request in the newspaper. “I wondered why we have this ritual and what specific foods might reveal about the person making the selection,” she said.

Since then, Green has decided to paint 50 plates every year until the death penalty is abolished in the U.S. She researches different last meal requests online and then transforms them into pieces of art with underlying stories.

“She wants to think a little bit about what that punishment says about us as a society,” Reichert said. “You know, the society that authorizes the killing.”

Staff at the Block Museum chose to exhibit Green’s artwork largely because of the opportunities that it would provide for community engagement. Reichert explained that, “because Northwestern has these various projects that deal with capital punishment and wrongful conviction and the criminal justice system, both at the Medill School of Journalism and the law school, we thought this actually is a really important project for us.”

The Block Museum has partnered with the Northwestern School of Law, the Medill Justice Project and several Evanston organizations to host different events during the exhibition.

Special events will include a panel about capital punishment on May 19 in partnership with the law school’s Center on Wrongful Convictions and a conversation about the role of social media in law enforcement on May 27. Details about these events can be found on the Block Museum’s website. The Block also hosted a talk with Green, Reichert and law professor Robert C. Owen on the exhibit’s opening day.

“’The Last Supper’ powerfully challenges the notion that we share no connection with those caught in the system,” Owen said in a press release. “Julie Green’s depictions of the last meals of the condemned movingly demonstrate the profound connections among all human beings that arise from our common memories and experiences of food.”

The exhibit is open to students, faculty and the public, and Reichert hopes that visitors will come not only to admire the artwork, but also to think about the story behind each plate.

“I hope people will come to think of these people as human beings and not merely as statistics or monstrous criminals who can’t possibly be thought of as human beings.” Reichert said. “I hope people can think about how they may be not so different from these people despite the very obvious differences in people’s circumstances that get them into a place like death row.”