If all 224 professors that McCormick employed in 2013 stood in the same room, you might not be surprised at what you’d see. A sea of men – 195, to be precise – would be dotted with 29 women.

in 2013 stood in the same room, you might not be surprised at what you’d see. A sea of men – 195, to be precise – would be dotted with 29 women.

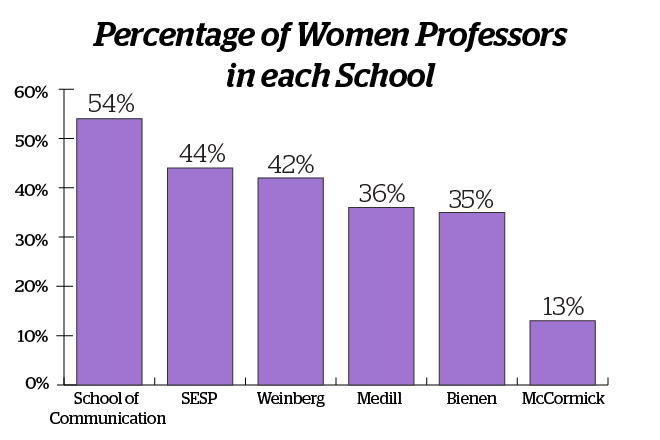

Thirteen percent of McCormick faculty members are women, according to numbers

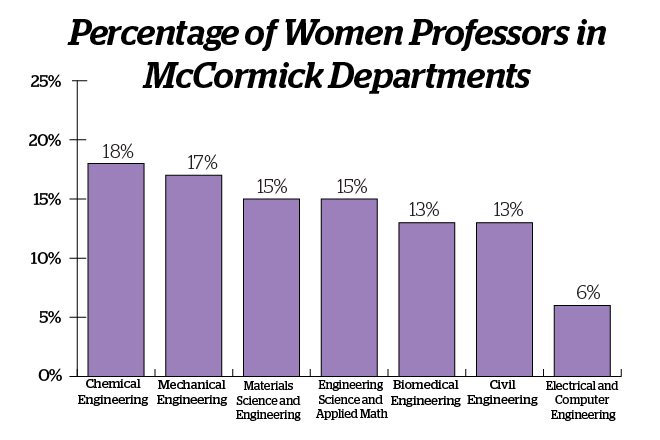

to numbers released by the university in 2013. The composition varies from department to department. The Segal Design Institute, McCormick’s innovation and design program, has the smallest gap, with 50 percent female faculty. The Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, on the other hand, has a school-wide low of 6 percent.

released by the university in 2013. The composition varies from department to department. The Segal Design Institute, McCormick’s innovation and design program, has the smallest gap, with 50 percent female faculty. The Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, on the other hand, has a school-wide low of 6 percent.

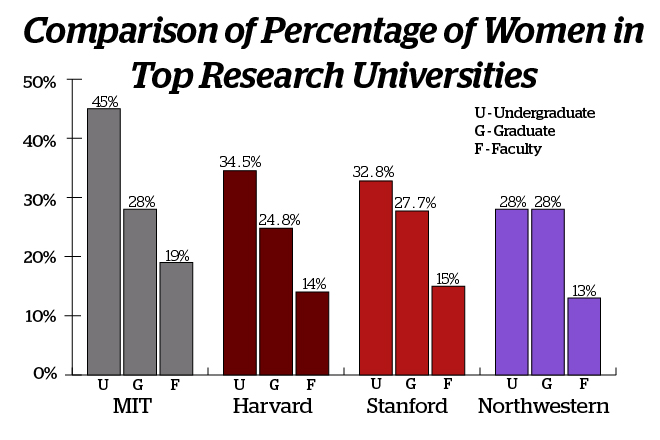

The numbers in McCormick, although in stark contrast to the other departments, are not unique to Northwestern. Rather, they’re a reflection of the traditionally male-dominated nature of engineering schools and the difficulties of changing faculty compositions. As societal norms about women in STEM have shifted, though, McCormick has made efforts to bring more women through the doors of Tech.

A shifting situation

Decades ago, women often found themselves in the vast minority at engineering schools.

When civil engineering professor Karen Chou received her Bachelor of Science at Tufts University in 1978, she started out as the only female civil engineer. While she was a master’s and doctoral candidate at Northwestern, she found herself “hanging out with all the guys,” drinking and playing softball. When she graduated in 1983 with a Ph.D. in structural engineering, her adviser told her that she was the first student that he could remember to graduate with that degree.

“I was the only woman in class, or the only woman in the department. Sometimes, the only woman in the college,” she says. “There was a lot of ‘only.’” She wasn’t aware, however, of the view that women didn’t belong in engineering until she became an assistant professor at Syracuse University in 1983. Tenured male professors would make overtly discriminatory comments, including one who directly told her that women did not belong in their field.

“He said that the worst thing that men did was to let women out of the kitchen,” she says.

The numbers have shifted since the 1980s, though, including at McCormick. The school’s 2013 incoming undergraduate freshman class was composed of 28 percent women, a full 10 percentage points higher that the national average of engineering schools.

For McCormick junior Megan Renner, an engineering camp for middle school-aged girls ignited her interest in the field. In high school, one of the camp’s sponsors then hired her as a mechanical engineering intern to work in a variety of different labs. Now, she’s majoring in manufacturing and design engineering (MADE), completing hands-on projects and taking classes in the Segal Design Institute . The lack of women in the sciences rarely crossed her mind.

. The lack of women in the sciences rarely crossed her mind.

“It was never a factor that I considered when I was picking what I wanted to do going into college,” she says. “I wasn’t afraid of being a female in a male-dominated field.”

Mechanical engineering major Kristen Stuzynski also took a lot of STEM-related classes in high school in which she was the only female student in the room. In McCormick, though, she says she doesn’t feel discriminated against or belittled because of her gender.

“Nobody has ever assumed that I couldn’t do something because I’m a woman,” she says. “I just feel like it’s all just based on your ability to do the work.”

ability to do the work.”

Representation a matter of empowerment, visibility

Whether students realize it or not, the presence of female professors - or the lack thereof - may make an enormous, if subtle, difference in their education

professors - or the lack thereof - may make an enormous, if subtle, difference in their education and future paths.

and future paths.

This rings true for biomedical engineering professor Wendy Murray, who cites her freshman year calculus teacher at the University of Notre Dame as her inspiration to major in math . Her professor was a young woman who deftly explained complex concepts and took the time to remember everyone’s name. Murray loved the class and decided to pursue a degree in

. Her professor was a young woman who deftly explained complex concepts and took the time to remember everyone’s name. Murray loved the class and decided to pursue a degree in the field. The professor had been the first woman to teach her math since grade school.

the field. The professor had been the first woman to teach her math since grade school.

“It’s a funny story to me that I really didn’t consider majoring in math until I had a woman professor,” she says. “I think it’s a really subtle, unconscious thing.”

Having models of female achievement in engineering would encourage students to become a leader in the field, both in academia and the industry, she says. McCormick freshman SueSan Chen echoes this desire for a mentor with whom she can identify. She considers her adviser, a young female professor in the industrial engineering department, as someone she can look up to. “It’s something to aim for,” she says.

Having female mentors in the faculty can also be crucial for students who are struggling or need more encouragement, Chou says. Although students who easily earn A’s might feel less unsure navigating the curriculum, “the majority middle ones” may slip through the cracks without the counsel of someone they can relate to and rely on.

of someone they can relate to and rely on.

“If they are looking for someone to lean on, or they feel more comfortable talking to a woman, those are the students we will lose,” she says.

A leak in the pipeline

The long game of improving gender parity is far from a quick, intuitive fix. It isn’t as simple as improving the numbers in the undergraduate population. There are many arduous steps throughout the process of entering the academic world of engineering.

fix. It isn’t as simple as improving the numbers in the undergraduate population. There are many arduous steps throughout the process of entering the academic world of engineering.

It’s first a matter of having high standardized test scores in math and science, then taking STEM-related classes in high school, then declaring an engineering-related major in college, then graduating with a bachelor’s degree and then deciding to enroll in doctoral programs .

.

And at each stage of the time-consuming, rigorous process toward academia, women leave. This phenomenon is often referred to as a “leaky pipeline.” Because of this formidable process, McCormick is far from the only engineering school with few female

toward academia, women leave. This phenomenon is often referred to as a “leaky pipeline.” Because of this formidable process, McCormick is far from the only engineering school with few female faculty members, especially when compared to other top research universities. Because these schools also tend to hire along the same lines of exclusivity, they’re drawing from the same small pool of candidates that have received training from certain elite schools.

faculty members, especially when compared to other top research universities. Because these schools also tend to hire along the same lines of exclusivity, they’re drawing from the same small pool of candidates that have received training from certain elite schools.

Starting conversations

In tandem with wider societal discussions about women in STEM, there have been policy pushes within certain McCormick departments to shrink the gap and support women.

For the biomedical engineering department, conversations about inclusion took off at a faculty retreat a few years ago. The “gender issue,” as biomedical engineering professor Suzanne Olds puts it, was mentioned in passing. A long-time male faculty member then stopped the conversation in its tracks .

.

“He said, ‘No, let’s stop right there. Let’s talk about this issue, because we haven’t talked about it. Let’s have a discussion,’” Olds says. “And it was a really great discussion, to get it out in the open .”

.”

Improved hiring policies and procedures within departments have been an important form of implementing change, says Olds. After the retreat, the department’s search committee for new hires was comprised of 50 percent women.

It’s crucial that actual members of the department, not just diversity-focused administrators, have a say in who they’re hiring and that they feel that they chose the right person, regardless of gender," she says.

“[Otherwise] it’d be a flop, because they’d think you’re hiring a female to hire a female,” she says. “And there’s all these kinds of animosity before they even start.”

As the head of the biomedical engineering department’s diversity committee, Murray says she’s determined to turn the ongoing dialogue into concrete change. Her department has talked in broad strokes about things they can do to improve women’s visibility, like inviting prominent women in biomedical engineering to come give talks to the students. But she says that more tangible plans, like the requirement of 50 percent women on search committees, can only come from talking candidly and taking collective action.

“I worry that, with having fewer women on faculty, that our department is vulnerable to the perception that it’s not a good place for women to be trained ,” she says. “There’s things that we can be doing proactively to emphasize that this is a good place for all students and all faculty to be successful. And I think that’s true.”

,” she says. “There’s things that we can be doing proactively to emphasize that this is a good place for all students and all faculty to be successful. And I think that’s true.”