"How could you be nostalgic for something that you never had in the first place?” Pamela Bannos asks her photography class. The Northwestern professor has been teaching photography in the darkroom since 1993. In recent years, however, she’s been seeing more students who have never done film photography before.

When Bannos polls her class on who buys and develops color film, two-thirds of her students raise their hands. “I was very surprised to hear that students completely in the Digital Age are still shooting color film,” she says.

Bannos distinguishes color film from black-and-white film. Whereas the latter’s aesthetic has remained the same over the years, digital photography has challenged color film. Yet college-aged kids are getting increasingly caught up in the vintage, not-so-perfect look of color film photography.

Similar to the recent resurgence of vinyl in the music industry, film photography has been gaining more attention from young consumers as the industry embraces a Digital Age and leaves analog behind.

“For a brief period, students became really into the digital, but then people got bored with it,” Bannos says. Surrounded by 140-character tweets and 30-second TV commercials, taking the time to capture and develop a single picture could be a relieving long breath in a treadmill lifestyle.

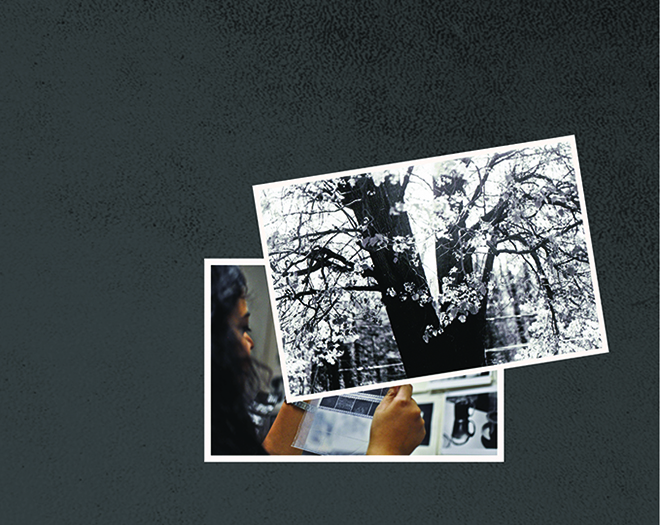

“[With] film, you slow down the speed, you add more light and you do all these things just to get the kind of photo you want,” says Weinberg senior Vanessa Gonzalez-Block, who started developing film in eighth grade in a basement mini-darkroom with her father. “I think it’s very much more a product of how I take care of the film as opposed to a product of what’s in front of me,” Gonzalez-Block says.

Unlike vinyl, which has been economically on the rise in terms of sheer production and consumption, film photography is becoming an endangered species. Polaroid announced that it would stop producing instant film in 2008, and Kodak announced its discontinuation of slide film due to low demand this past March. Closer to home, the CVS on Sherman Avenue recently closed its photo lab.

“What I’ve been impressing upon my students is that you might all be the last people to be using this kind of medium,” Bannos says. “When you think about it that way, it makes it more important because you’re all part of this history.”

Maybe that’s the nostalgia 20-somethings foster for things we never had in the first place. We’re fascinated by things from the past because they’re foreign concepts, and so we try to recreate them. Take Instagram. The app is the perfect intersection of everything 21st-century: social media, mobile platforms and high-resolution phone cameras. The catch, of course, is that it’s mimicking the look of vintage cameras from the ‘60s and ‘70s. “Most of it has to do with how fast things change and how fast the students have gone through from one medium to the next to the next,” Bannos says. “Three mediums later, you forget about what the original one was anymore. And then that comes back again. It’s like Instagram is doubling back to the look.”

Disposable cameras, which are also becoming more popular, are one step closer to the real thing. Initiatives like The Impossible Project, which started manufacturing instant film in 2008 after Polaroid’s discontinued production, have gained popularity among a niche market.

“You’re actually getting the film and the object that Instagram is trying to emulate,” Bannos says. “It is genuine, actually, because it’s analog and you’re doing it that way.”

When she asks her students why they do this, Bannos is surprised that there are practical reasons: No one wants to bring a huge DSLR to a party, and losing a cheap disposable camera is much less expensive than losing a smartphone.

Gonzalez-Block cites the aesthetic of disposables as another reason. “I really like disposable cameras because I like the graininess of it,” she says. “You only have so many shots, and so each shot kind of helps tell a story. They’re for occasions, and so they’re very much about storytelling as opposed to a beautiful photo.”

In her photography classes, Bannos points her students to the endangered state of film photography. “If they like the analog, they’ve got to start saying it louder,” she says. Because the industry as a whole has moved on to digital, producers are eliminating the film sector—but if a demand for film increases, there will again be a market for the medium.

“Film is just so expensive, it’s so not practical,” Bannos says. “But it is kind of awesome.”