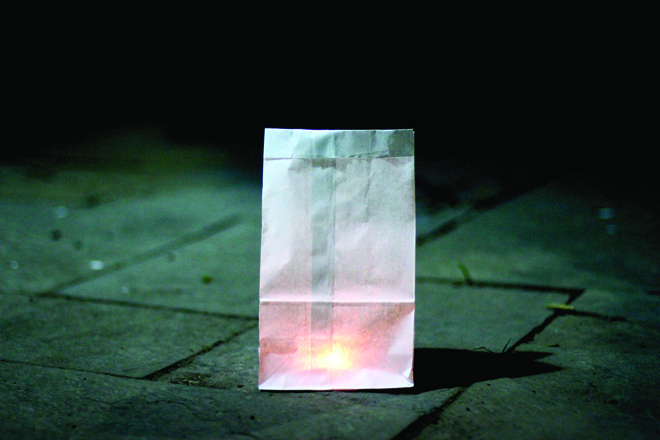

I sat in front of a luminaria, with my face buried in my hands and the skin of my legs stuck to the floor of SPAC’s tennis courts. An a cappella group was singing nearby, but I had lost all sense of space. The candlelit white bag read “In memory of Jun Bergado. Never will forget you dad” in my chicken scratch.

April 2011 wasn’t the first time I broke down during a Relay for Life Luminaria Ceremony. I was used to it. It happened every year of junior high and high school, an annual tradition where I’d find myself anxiously waiting for the event to begin, knowing I’d eventually end up in a pool of tears. But it was the first time people from college saw me in this catatonic state.

As most people continued to walk around the trail of luminarias that lined the tennis courts, I was frozen in place, sitting cross-legged in front of my dad’s tiny memorial. I could hear footsteps behind me. Hands would grab my shoulder, give me a squeeze, then disappear. Sometimes arms would wrap around me, attempting to provide some sort of comfort.

I had no clue whose hands and arms were the ones coming to support me. They stayed faceless. Their touches felt both distant and close. With each grab and hug, I couldn’t tell if I was becoming more annoyed or comforted. They felt both invasive and solid.

Then the frustration hit. What had I done, becoming some sort of public pity party? I forgot about my irritation with everyone else and instead became frustrated with myself. I had let myself become a petting zoo, where people could come and comfort the poor puppy who was caught in a web of snot and tears.

I finally forced myself to get up. Avoiding eye contact, I walked off the tennis courts and into the men’s tennis locker room. The lights were off and I didn’t bother looking for a switch. Darkness. It felt nice.

----

The pangs hit me at the most random times. I’ll be sitting in class, trying to pay attention, and the professor will say the word “parents.” Suddenly my chest feels like it has been struck by lightning. Sometimes I’ll be standing against a basement wall with a red Solo cup in my hand, and a whirlwind of memories will distract me while I’m talking to friends. In bed, I’ll be tossing and turning when his voice drifts into my head. The flood of tears begins almost instantly, and I try to hide them from my roommate who, thankfully, sleeps like a rock.

My dad died of lung cancer when I was 12. He was never a smoker. He was my chauffeur, and he loved driving out to the desert. He was my tutor and taught me how to add fractions when I wanted to get ahead in Mrs. Steinart’s math class. He was a lot of things.

He was there to let me pick my own mix-match of clashing clothing when my mom wasn’t home. He was there to teach me how to ride a bike, which really meant he let me fall until I couldn’t fall anymore. He was there when I graduated from elementary school and entered the confusing realm of junior high. But he stopped being there after my mom, aunt, two sisters and I watched Riverside National Cemetery workers lower him six feet into the ground on a sunny California day in May 2005.

He wasn’t there to give me a firm handshake when I graduated from high school. He wasn’t there to congratulate me when I got my Northwestern acceptance letter. He won’t be there when I get my first real job, when my younger sister walks down the aisle at her wedding or when my first kid is born.

“It’s a silent battle,” says Medill sophomore Laken Howard, whose dad passed away a few weeks after she graduated from high school. “Nobody knows it about you.”

Even with the six-year difference between our fathers’ deaths, it feels like we have the same battle scars, from a war most of our friends aren’t aware of.

“When something good happens to me, there’s a list of people I call,” Howard says. “My mom, my best friends. I wish I could add him to the list.”

----

Three months ago, I was doing some schoolwork at Unicorn Cafe when a man and two children entered. They took a seat at a larger table adjacent to mine. As I tried to concentrate on a pile of readings, the trio took out a stack of coloring books. The brother and sister began fighting over the colors, deciding who was going to get the red crayon first. Their dad was up at the front counter when the young boy looked up and caught me staring. He was probably about 7, and he smiled at me. He waved as their dad came back with two hot chocolates topped with whipped cream. The dad nodded towards me.

I spent the next 20 minutes in the bathroom blowing my nose and wiping my eyes. I wasn’t stepping back into the cafe to collect my belongings until I had collected myself.

Sometimes that silent battle becomes the loudest thing around you. There are reminders that you can’t shake off, reminders that trigger the most visceral reaction within you.

----

Loss isn’t rare among college students. A survey conducted by David E. Balk, a former Kansas State University professor who studies bereavement, found that 81.8 percent of respondents indicated a family member had died within an average of 4.5 years prior to the survey. However only a few reported the death of an immediate member of the family such as a mother, father or sibling. Most of the family members who died were grandparents or great-grandparents, at 67 percent. Balk’s study shows that there are more people like me than it may appear.

It’s hard to tell when there are no physical markers. Loss cuts into you like a knife to the stomach, slowly churning and letting your blood run out. But there are no scars, no bloodstained clothing. Just that silent battle: a sick cycle, where the muteness keeps you silent to others, unsure of who else might have the same wounds.

Sometimes all you want to do is scream about it, to blame it for why you’re having a shitty day or why you can’t get out of bed. But that fear—the fear that you’ll become a pity party again, that people will see you differently—is enough to keep you quiet.

Karrie Snyder, a lecturer in the sociology department at Northwestern, says that when a parent dies, a child receives a label similar to the one a child with divorced parents takes on.

“No matter how many times the other parent remarries, or the status of the parent when the parent dies, I think young people have a label put on them,” Snyder says. “A sympathetic label.”

And seeing that label placed on you is a whole different struggle. When people find out my dad’s dead, I see their eyes go dull, their lips quiver. They want to say something and feel like they should comfort me in some way, but instead there’s just a new lens through which they view me.

“Why can I not just be like, ‘My dad is dead?’” Howard says. “It makes me feel awkward. Even close friends will freak out.”

It’s difficult straddling the line between wanting to talk about your loss and not wanting people to see you differently.

According to Snyder, there is a level of “othering” when it comes to people’s assumptions about parents. Many people come to college and perceive others based on assumptions until they find out the truth.

“You’re admitting to something that makes you different from the norm,” says Medill junior Lauryn Chamberlain, who lost her father Fall Quarter of her freshman year. “People don’t know how to react to it.”

----

So, when’s the time to open up? When’s the time to vocalize that I miss him? Northwestern CAPS offers a variety of services to help students—crisis intervention, group therapy, eating concerns assessment and stress management are just a few—but nothing explicitly for dealing with parent death. Nothing for those days when the man at Unicorn Cafe orders hot chocolates for his kids.

I hate flying home on breaks and not seeing him waiting in the car at LAX alongside my mom and younger sister. I hate that next year at graduation, when I’m wearing that purple gown and supposed to be excited for the next step in my life, there will be a knot in my chest, something holding me back.

“He won’t be there at certain key events that you’d imagine,” Chamberlain says. “Think about your parents being there when you get married, meeting your kids.”

We’re different. We’re the kids who had to say goodbye too early, the college students who had to bury our parents before we had to pay off a credit card.

Do I let that define me? I hope not. It’s not the be-all, end-all. I try to remind myself that I’m not a certain way because of one thing.

----

It was one of those days when I wanted to remember, at the beginning of my final semester of high school. I knew the memories ached, that they stung, but it was better than the feelings of numbness and forgetting that were slowly suffocating me.

I snuck out of the apartment, grabbing the keys to the ‘86 BMW convertible that my mom never sold after we moved. I put the key into the ignition and turned, waiting to hear the car roar. As the engine warmed up, so did old memories of driving to get Thrifty’s ice cream on hot summer days with the top down. I was sitting in the same seat he used to take.

The apartment we moved into between seventh and eighth grade wasn’t far from the house where I spent the first 12 years of my life. A right turn onto Valley View, a right onto La Palma and a left into the residential area where he taught me how to ride a bike. I parked in front of the lawn where I spent afternoons pretending I was a Power Ranger and where my sister got bit by the neighbor’s dog.

My childhood home was simultaneously foreign and familiar. Once painted powder blue, it was now dark brown. In the driveway, a maroon suburban SUV took the BMW’s old spot. From the driver’s seat I gazed at the house, envisioning the kitchen where I celebrated birthdays and the backyard pool where he taught me how to swim.

I was debating knocking on the front door when a man from the house across the street came out. I instantly recognized him as Paul, the man who would let me gaze out his telescopes and grab my handball from his backyard whenever I’d bounce it too high. I got out of the car and walked towards him.

His expression as I got closer was one that you’d make when a stranger walks towards you. I was a stranger, no longer the wide-eyed, chubby five-foot-two boy who had moved away five years prior. The person approaching him was a teary, lanky six-foot-one adolescent still trying to comprehend what he had lost.

----

At my dad’s funeral, I told some short anecdote about him letting my sister eat cookies. I found the Word document recently, and half-laughed, half-cried as I read how I conceptualized his death almost 10 years ago.

Today I try to put together all the different ways my dad’s death has affected me. There are some days where I feel like it’s done nothing but fuck me up, but there are other times I tell myself everything happens for a reason and I’m a stronger person now. What I can’t ignore is the fact that the loss had a big part in making me the man I am today. But there’s still no easy answer for how different today might have been if I hadn’t had to say goodbye.

Would he be proud to see the person I’ve become? Proud of my successes, my faults, my doubts? I think he would. I try to tell myself that he is. But that looming insecurity—the simple truth that I will never hear him say it, or weirdly communicate it through some gifting of an odd pen that sitcom fathers tend to do—is something I don’t think will ever go away.

I look in the mirror and see limbs I’ve grown into, pubescent acne that’s faded away, facial hair I thought I’d never grow. I’ll flash back to a fading memory of my mom speaking at his funeral. She stood at the podium, tears in her eyes, talking about all the parts of him she saw in my sisters and me: my older sister with his compassion and level-headedness, my younger sister with his laugh and love for animals. As for me, I had his brains and quick wit. Now I’m 20, and I wonder which parts of me come from the man he was.

A friend of Chamberlain’s who also lost a parent told her something valuable: “Don’t expect to be able to relate to people in the same way. The connection you make when you love people, it feels small compared to other things.”

What worries me even more is the forgetting, the numbness that pushed me to drive to my childhood home. His voice has slowly faded into the depths of my memory, and now I can hardly hear the words “mijo” and “Gabriel” when I close my eyes. I still remember his one scoop coconut-pineapple, one scoop pistachio ice cream order at Thrifty’s. But I fear the day when I’ll forget.

In those moments, when I see a dad bring his kids a round of hot chocolates, I want nothing more than to be 7 years old again. I want to go back to those late nights when I’d hear my dad’s truck pulling into our driveway and I’d hide under the kitchen counter. He’d come in, set his keys down, take off his musty work hat and start making himself a late dinner. He’d crouch down and look in the cupboard for the soy sauce—the perfect moment for his son to pop out and climb onto his back.