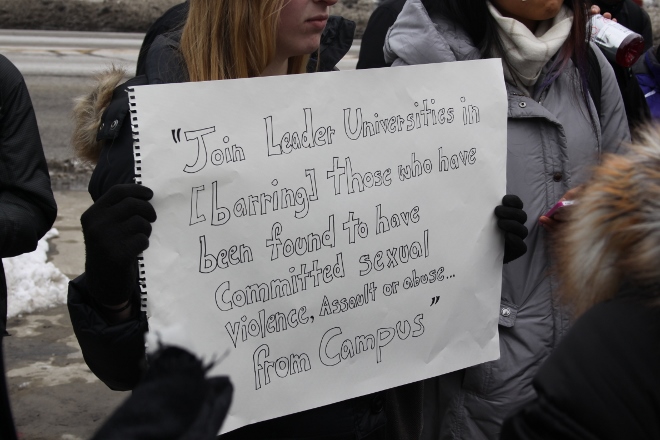

A student protests the university's response to sexual assault allegations against professor Ludlow at a march on campus last winter.

Mitchell Caminer / North by Northwestern

Students responded with anger and confusion last Thursday when a federal district court dismissed a current Medill senior’s Title IX lawsuit against Northwestern for allegedly failing to respond to her complaint that a professor sexually assaulted her in 2012.

Weinberg senior Alex Grant summed up the consensus of many on campus with a simple tweet: "This makes me sick."

The ruling also left many questions about how Northwestern handled the situation from the very beginning and why the courts decided the University isn’t liable.

When philosophy professor Peter Ludlow allegedly sexually assaulted the then-freshman, the student reported the incident to another professor, according to the court’s ruling. Director of Sexual Harassment Prevention Joan Slavin was informed and began an investigation, which consisted of reviewing documents and other information as well as interviewing the victim, Ludlow and other witnesses.

The story is slightly different in the student’s lawsuit against Northwestern. According to the lawsuit, the University established a committee “to determine what action should be taken against Ludlow” and that the committee decided Ludlow's employment "should be terminated.” The lawsuit, however, alleged Northwestern “ignored its own committee’s decision and recommendation and continues to employ Ludlow as a professor.”

So why wasn’t Ludlow fired in the first place?

Because the investigation was conducted from Slavin’s office, we do not officially know whether a committee or Slavin herself was responsible for the findings. There is also no evidence that the report recommended firing Ludlow, as the student’s lawsuit alleges. Slavin declined to directly address the litigation via e-mail.

Professor Laura Beth Nielsen, the director of Northwestern’s legal studies program, said that, according to court documents, Slavin’s report issued findings but made no recommendation about a punishment. Northwestern denied the student’s claim that Slavin’s report officially suggested termination.

Nielsen said that according to University policy, Slavin’s report would go to then-Dean of Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences Sarah Mangelsdorf. What happened next is unclear.

“The dean, for sure, made a recommendation, and [Ludlow] appealed to the Committee on Cause,” Nielsen said. “We don’t really know what happened there, but the punishment went forward.”

The Faculty Committee on Cause, whose seven members are selected annually by the Faculty Senate, “reviews and mediates disputes between faculty members and the University administration,” according to Northwestern’s website. These disputes can range from a minor sanction to termination, and either faculty members or administration can initiate reviews.

According to the lawsuit, Slavin said she would work with the Weinberg dean’s office “on implementing needed corrective and remedial actions.” Slavin, however, told the student “Northwestern would not share details of disciplinary and corrective actions taken against Ludlow because of its confidential personnel nature.”

Why was the case dismissed?

Judge Harry D. Leinenweber wrote the court ruling which dismissed the student’s lawsuit, stating, “Northwestern immediately conducted an investigation into the allegations and issued a report finding them well taken. It took remedial action which consisted at least in part by instructing Ludlow not to have any contact with Plaintiff. [The student] does not allege that Ludlow violated that instruction, so Northwestern took timely, reasonable, and successful measures to end the harassment.”

Professor Nielsen explained the implications of this ruling and why Northwestern wasn’t liable.

“Fundamentally, the dismissal this week was the victim’s case against NU for failing to ensure an equal educational environment,” she said. “When a university knows that sexual harassment has occurred, the burden is for the university to do something more than be ‘deliberately indifferent’ to the victim.”

In other words, the student’s lawsuit accused Northwestern of taking no action, while in reality they did “slightly more than nothing,” according to Nielsen.

“The court said that the ‘no contact’ order was enough,” Nielsen said, referring to the University’s instructions to Ludlow not to retaliate against or contact the victim.

Furthermore, the ruling said, “If Northwestern had learned that its response was proven to be inadequate to prevent further harassment by Ludlow, it would have been required to take further steps to avoid liability.”

That is to say, if the student had complained Ludlow continued harassing her after the University responded, then the school would be liable. Since either Ludlow was not harassing her or the University was not aware if he was, Northwestern cannot be held responsible.

What is the University saying in all of this?

Vice President for University Relations Alan Cubbage issued a statement Thursday on behalf of the University in response to the court’s ruling.

“We’re pleased that the court dismissed the lawsuit,” he said. “As we have said previously, Northwestern is strongly committed to responding appropriately to complaints of sexual harassment and sexual assault, and as the court ruled today, the University did so in this case. Northwestern complied fully with its procedures, conducted a prompt, fair and thorough investigation and took a number of corrective and remedial actions.”

Why was he not punished more harshly?

The student said the assault affected her academics, caused her to attempt suicide and gave her post-traumatic stress disorder and panic attacks. Furthermore, his continued presence on campus caused her to miss classes so she wouldn’t have to run into him again.

However, Cubbage has maintained that the University responded appropriately to the incident.

“Northwestern has established procedures for responding to such complaints – and those procedures were adhered to in this incident,” he said in a February statement about the lawsuit.

The court’s ruling states victims are not allowed to make “particular remedial demands” based on the precedent set in Davis Next Friend LaShonda D. v. Monroe.

As far as why Ludlow was not punished further, Nielsen said she doesn’t know.

“It seems absurd to me,” she said. “I disagree with this legal standard, because it does not do enough to protect student victims and allows the sanctions to happen behind closed doors. We need some rules that say if our process finds that a professor did X, he or she gets A. I think our community has a right to know what the standards are.”