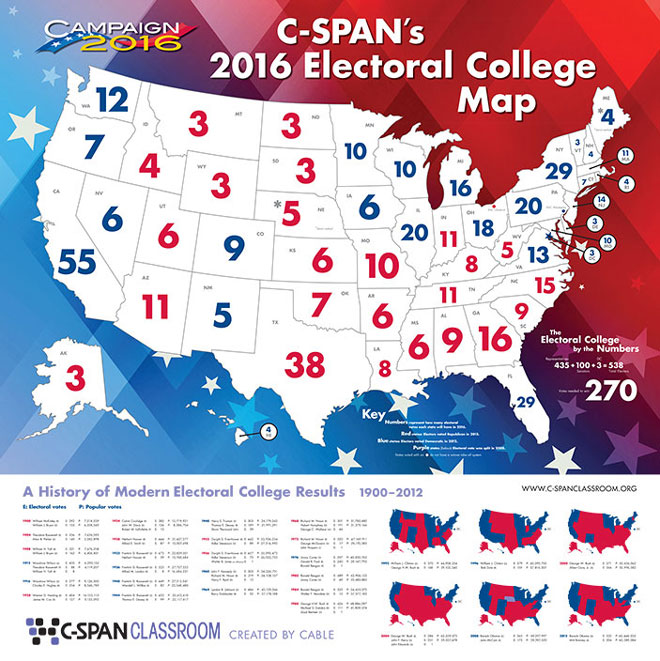

Graphic courtesy of C-SPAN

Ahhh, the electoral college. It conjures up images of red states, blue states, swing states, 270 to win, 538 and unnecessarily complicated solutions to problems. Let’s break down exactly how the United States counts the votes for president and understand why we ended up with the #aesthetic map of red and blue states.

How did the electoral college start?

The United States was founded in a world where the fastest form of communication was a letter on a horse. A national popular vote would have been very hard to correctly record, so the founders created an alternative system where political elites traveled to Washington, D.C. after the general election to cast the votes for president.

These elites, or electors, ranged from party operatives to members of Congress. Instead of voting for president directly, Americans instead vote for electors in November who then vote for the candidates in December.

It was also a matter of control. As musical superstar Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers, the president should be elected “by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station.” In other words, the founders didn’t really trust the common man to make political decisions.

So, how does it work?

Basically, the number of electors is equal to the members of Congress. The house (435) + Senate (100) + the District of Columbia (after a constitutional amendment gave the District voting rights in the 1960s, 3) = 538. The electors are then divided between the states based on the number of Congresspeople in each state. The lowest possible amount is three (senator + senator + representative) and it goes up to 55, the amount California has. When you vote for president in your state, you’re actually voting for an elector that’s pledged to support your candidate. Most states run their elections on a winner-take-all basis, except for Maine and Nebraska, which award two electors to the winners of congressional districts in addition to the winner-take-all for the state. The candidate that gets the majority, no matter how small, automatically wins all the delegates from that state. Add up delegates until you reach 270, and congratulations to the new president. Simple, right?

What’s the problem with it?

Remember in the last paragraph when you read that electors vote for your candidate? Think of it as a courtesy, not a requirement. Yeah. Only 29 states and D.C. punish, usually with fines, electors for not following the popular vote. It’s not clear if those laws are constitutional. In 21 states, including Illinois, electors are free to look at the popular vote, say “meh,” and then vote for whoever they want with no consequences. This has happened 157 times in American history.

The electoral college is also tie-tacular. If there’s a 269-269 split (or if no candidate gets above 270), the election is thrown to the House. But, there’s a catch. House members don’t vote individually – they vote as states. And there are 50 states. Sigh.

In addition, the vice president doesn’t come along for the ride. Senators, voting individually (because why not), get to pick. There are 100 senators. Also, since the Senate and the House vote totally independent of each other, it’s possible to end up with a president from one party and a vice president from the other!

How does it influence political campaign strategies?

All votes are equal, but some are more equal than others. Since states are winner-take-all, if a candidate knows that a state will vote 80/20 for him he doesn’t need to spend any resources there. That’s why we have “red” states and “blue” states. On the other hand, if a state is very close to 51/49 for a candidate, he will spend lots of time and money there to gain those sweet electoral votes – the birth of “swing” states. Thanks to these margins, it’s possible to win the popular vote and lose the electoral college. Counting yesterday's election, it’s happened four times in American history (the second most-recent being in 2000).

There you have it. You finally understand the electoral college – the least complicated, absolutely foolproof way we electors choose the president.