In the 1950s, Northwestern had a big problem. The university wanted to expand following World War II, but there was simply not enough space. The solution? Lake Michigan. In 1962, Northwestern started to expand eastward by creating new land off its coastline. When construction finished a few years later, the lakefill we now all know and love had doubled the size of the university’s campus.

But if getting more land was the central issue, why did Northwestern make a big chunk of the lakefill, well, a lake?

The Lakefill was inaugurated with much pomp and ceremony in October 1964. Adlai Stevenson was the distinguished speaker – a Northwestern graduate, two-time Democratic presidential candidate, and JFK’s ambassador to the United Nations.

“And I’m also deeply indebted to you sir, and all of the trustees and your associates, for this invitation to participate in the dedication of this magnificent and imaginative new campus.” Stevenson said in the dedication, whose audio we obtained courtesy of the Northwestern University Archives. “I only hope it doesn’t blow away before we get through the inauguration!”

But the idea of a lakefill was not just a product of the 1950s. Kevin Leonard, Northwestern’s University Archivist, says dreams of eastward expansion stretch as far back as the early 1890s.

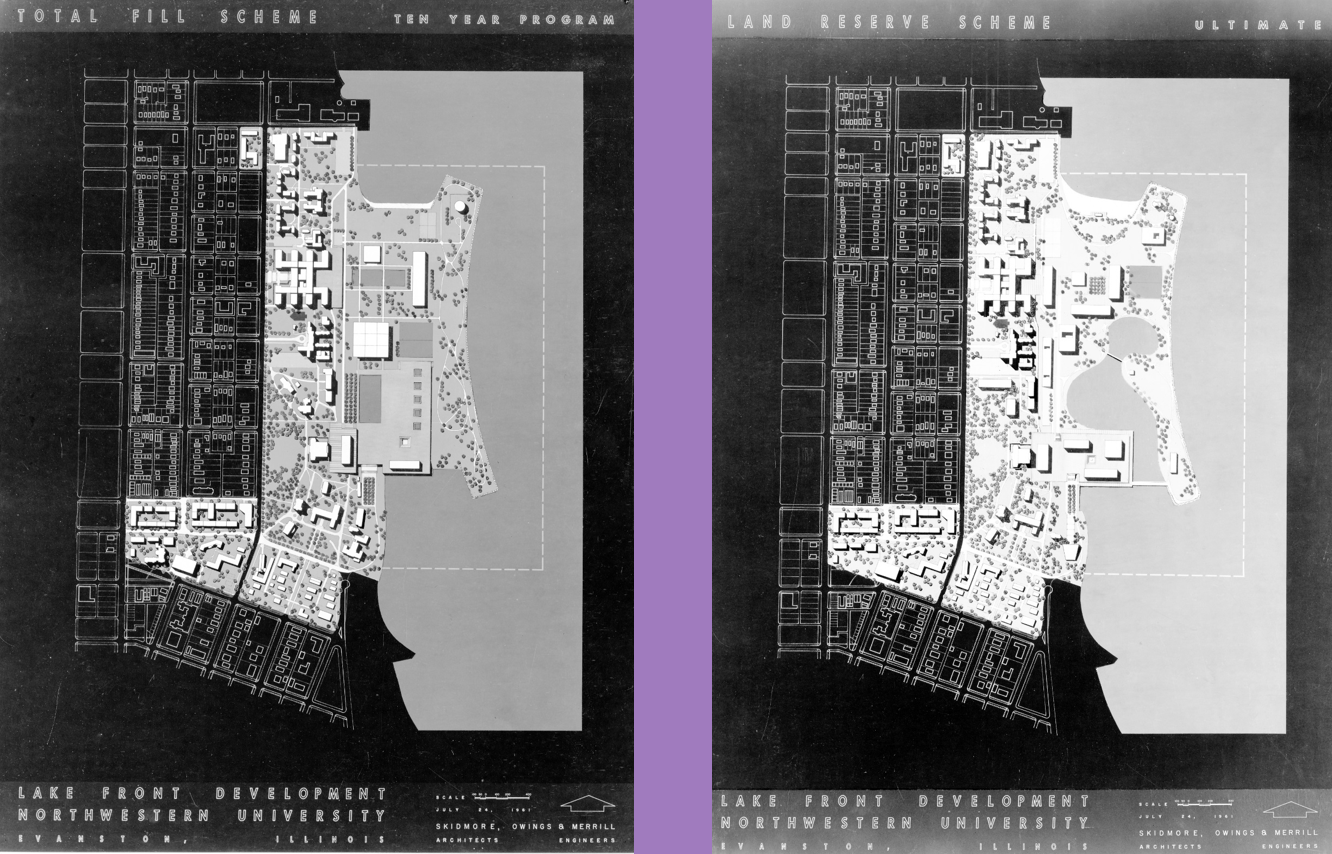

“Those earlier plans envisioned roadways, lagoons, a rowing pond, a polo field out on the lakefill,” Leonard said. “There’s a great architectural sketch that depicts a landing strip for aircraft out there. But they were pipe dreams at the times they were presented.”

Those plans became closer to reality following the Second World War. The university needed to expand, but doing so by buying parts of the City of Evanston proved a big challenge.

“The university, in the 1950s, did some building on the other side of Sheridan Road, some dormitories and living units – and those created discord with the greater Evanston community,” he said. “It was very difficult to get the necessary permitting, and it raised the ire particularly of the citizenry living in the areas adjacent to Northwestern.”

There was fear that the university would eventually grow all the way out to Ridge Road, and these fights convinced university leaders that they needed a new option. Also, there were cost considerations.

“Building on the other side of Sheridan Road, west of Sheridan Road, is expensive,” Leonard said. “We’re bordered by a residential area – and a nice residential area – and those properties can cost quite a bit of money.”

Filling in a big chunk of Lake Michigan proved more practical. New plans were commissioned and drawn up by architect Walter Netsch, who would go on to design many of the new buildings constructed on the lakefill, such as the University Library and Regenstein Hall of Music.

But there was a small hitch – Northwestern did not actually own the land underneath the water. Following a special, unanimous act of the Illinois State Legislature, Northwestern bought 152 acres of lakebed for a little over $15,000.

“It approximately doubled the size of the Evanston campus, so it’s a really pivotal moment in Northwestern’s history.”

Construction began in 1963, with barges dumping an estimated two-million cubic yards of sand into the lake. The total cost? $6.5 million. Leonard says the lakefill made Northwestern what it is today – to the point that without it, the university would just be another small liberal arts college in the Midwest.

“It allowed so many of the buildings that you see now – and not only the buildings, but the functions that go along with those buildings.”

John Searle, the president of the board of trustees during the Lakefill’s construction, agreed. The lakefill now hosts many of Northwestern’s new buildings dating back to its construction, from the University Library and Norris University Center to New Kellogg and the S.S. Bienen.

But if more land was the main issue, why did Northwestern’s new lakefill include such a large lake? “Fake Michigan” takes up a significant amount of space – about 25 percent of the total area. There’s got to be a reason for that.

Ultimately, Leonard says, it was all about aesthetics. “Fake Michigan” served as a way to keep Northwestern’s old campus close the lake by bringing the lake inland.

“You can see some of his earlier plans where he’s sketching out the lakefill without a lagoon, but pretty early on you see a lagoon as part of his drawings,” Leonard said. “In fact, the earlier you go on his drawings that incorporate a lagoon, the lagoon was much larger.”

However, Netsch’s proposal wasn’t a slam dunk. There was actually some early pushback from university administrators.

“Like, why are we building this?” Leonard said. “If we need land, let’s get more land!”

Ultimately, the lagoon stayed. Leonard says it eventually gained a practical purpose as a source of cool water for the university’s new facilities plant, which was built to cool the new buildings on the lakefill. However, that wouldn’t last.

“As the lagoon silted up, the volume of water in the lagoon was reduced,” Leonard said. “It became shallower and shallower, and the temperatures of the water in the lagoon rose.”

That water would have to be cooled itself to be used in the chillers, which would cost even more money.

“Ultimately, the university had to dig a channel through the lakefill and send a pipe out into Lake Michigan,” Leonard said. “So, the water used for the chillers is drawn directly now from the lake rather than from the lagoon.”

But “Fake Michigan’s” practicality lives on – it was switched from a cool water reservoir to a hot water discharge pond.

“So, you’re not creating thermal pollution by putting water that’s too warm into the lake,” he said.

Side note here – we reached out to facilities management multiple times for this story, but they declined to comment.

Leonard says Northwestern’s even considered filling the lagoon in – plans were made public in the early 2000s to add four acres of land to campus by filling in part of it. But this proved very unpopular, and the university backed off.

So, “Fake Michigan” is likely here to stay. Stroll along its Western shore, and you’ll catch a glimpse of the masses of extra-large carp that live beneath the tranquil waters.

“They will sense you!” Leonard said. “They will discern your presence and come right up to you, and they will expect some form of reward for doing that.”

Next time on AskNBN – Northwestern was given a rectangle of underwater land from the state of Illinois to build the lakefill. But the university only used about half of it, and still owns an underwater portion of Lake Michigan. Could there ever be a Lakefill Two?