Last winter, I went searching for Alvina.

I went searching for a woman with whom I share a quarter of my DNA and an unknown amount of myself. I went searching for a woman who embodied evanescence at its finest, soon passing out of mind, memory and existence. I looked for an enigma and a paradox. I searched for my grandmother.

My parents told me little of her life and even less of her character, other than that she was a force to be avoided. Alvina – my father’s mother – was a legend the family wished to conceal. And since then she has remained, to me, a mystery.

When I first started my research, I had no way of knowing if she was alive. My father had fallen out of contact with her for what now amounted to a majority of his life. The last message he received from her was discarded – my grandfather said that responding to it would launch my father and his family into “purple hell.” I knew that she divorced my grandfather in the late 1970s, and that she eventually found herself psychologically unfit to care for her children. Her reported diagnosis, however, had gone unknown.

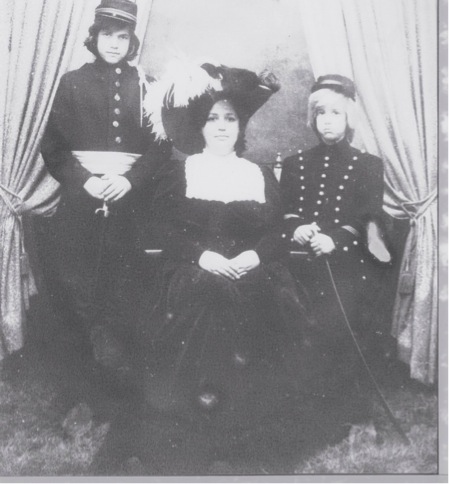

I began with the intention of putting her mystery to rest. I left with the responsibility of telling my father if his mother was still alive. I can’t say what exactly compelled me, other than an itching, consuming curiosity. It all began when my uncle sent me a scan of an old newspaper marking the occasion she married my grandfather. In the center of the page is her picture: smiling for the camera, her details obscured by the dotted and dated print.

I mention this interest to my father, which sparks a small email correspondence between the two of us. He explains in great detail the few memories and impressions he had of his mother, which include an early mention of her unconditional love. And this strikes me, because I’ve never heard the phrase “unconditional love” applied to Alvina. I thought of her largely as an agent of creation for my father, and an early childhood figure that was transient at best. Her first name isn’t even “Alvina.” Her first name is “Mary,” but “Alvina” is the name I use when I search for her and when I write for her. There is something unique about it – fitting for a woman of such conspicuous mystery.

But these memories of unconditional love soon turn into portraits of a woman engaged with visible darkness. As the messages continue, my father begins to recall Alvina sitting in her chair and crying for no definable reason. This is the grandmother with whom I’m intimately acquainted: the fallen Alvina.

Shortly thereafter, my father was moved to Mexico. By the time he returned, his parents had separated, and this is when the family began to suppress my father’s exposure to his own mother. Not long after, my father, my uncle and my grandfather packed up their belongings and moved from Los Angeles to Eureka, California. Alvina’s sons visited during the holidays for only a couple of years.

My father recommends my grandfather as an important resource. I call him a few days into the project and ask him about his memories of his ex-wife and long-removed lover. He says that her problems were psychological – they amounted to what he calls a “fear of living.” Alvina apparently didn’t leave home until she was 24, when she moved from Waterloo, Iowa, to work in Washington D.C. for the government as a secretary.

During one of her psychiatric visits, she was told she suffered from “issues of extreme inadequacy,” an opaque diagnosis at best. Another psychiatrist insisted that the mothers in Alvina’s family had been psychologically unbalanced for generations, and passed their problems to one another through the medium of environment.

These are the only details my grandfather can remember of her psychological history, and he doesn’t speak much of his memories of her during their better years together. The consequences of her clinical depression seem to have erased any memories of a normal woman. Then I ask the final question: “Do you know what ever happened to her?”

He tells me there was a Mary Daly who died on October 24, 2012. Her middle name was Alvina.

We go over some of the details and wrap up the phone call. He says it was good to hear from me, and he’s glad I’m doing well. I tell him the same. In a way I find myself disappointed in never having affected the life of my grandmother despite the removal. And while some questions concerning her previous whereabouts remain unanswered, I succeed in finding some closure.

I am the person who first delivers the news of Alvina’s death to my father. We share disappointment, but not melancholy. I never knew her like my father. And now I will never know her any more than I do now.

Last winter, I went searching for Alvina. And this is what I found: a woman uprooted by her own history, launched into a deep sadness that tore her away from her family. But she was a complex and sophisticated woman, and tracing her has been something of a rite of passage. It marks my independence from the family dictum of leaving her alone.

When I first went searching for Alvina, I wondered if I would find the best or the worst in what we shared. I wondered if I would look at her pictures by the end of it and find a reflection of my own image. Before, she was merely a symptom of my family’s medical history, an artifact of a depressive illness that has struck me in the past. Today she has a character, a life, and a story, and it makes me wonder to what extent her suppression was a good idea. I am no worse off for having found her, but from what I can see, she is worse off for having been withheld.

I no longer search for her – I remember her. And perhaps this is the single duty a grandson in my position could perform.