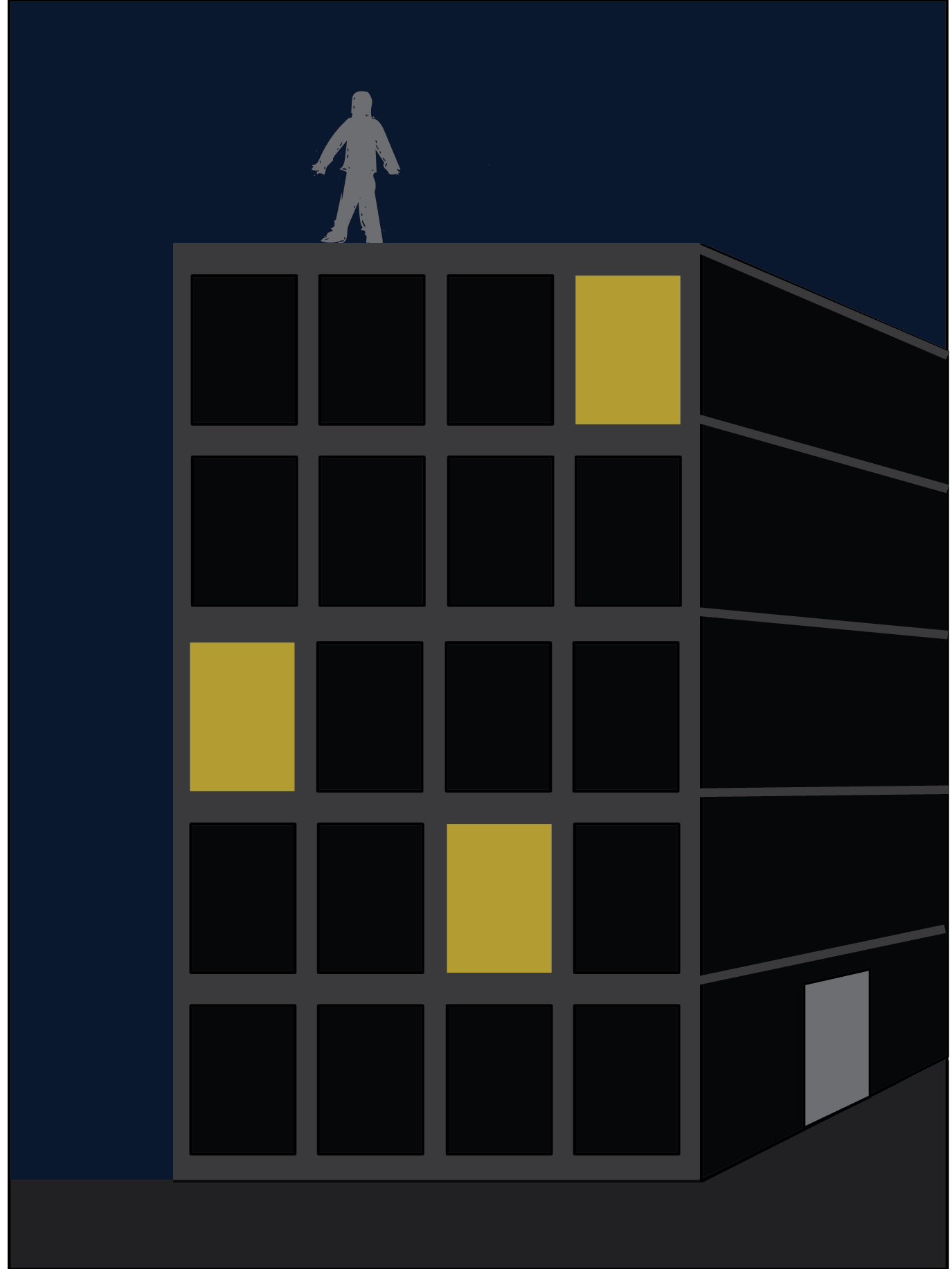

One morning, Salem Pierce ejected himself from the fifth-floor window of his apartment. Among the items he left were a collection of compositions dated by several decades and a few notebooks full of stories written for no one in particular.

We cannot be sure of his attitude toward life in the weeks prior to the incident because he left no written record, but he documented his life well up to this point which allows me to say the following with confidence:

Salem had traveled much, but only as a consequence of his parents’ work and lifestyle. By the time he left his first school at the age of nine, he could play some songs, but only one hand at a time. When he left his second at the age of 11, he had grown so distracted by his friends and the inevitability of losing them that he made no progress in music.

He looked old for his age. At 15, he returned to the piano and began practicing in bars, which is to say that he practiced primarily through various states of intoxication. He had difficulty recalling his technique otherwise. At 19, he met a woman his age and launched a stunning and passionate romantic affair that lasted two months. Salem never pursued sex again, considering it a distraction from love.

On rare occasions that Salem did develop friendships, he found them difficult to maintain. He did, however, pursue them adamantly – nothing was more valuable to Salem than a trusted friend, no matter the brevity. He had many of them scattered around the country and eventually around the world. They remembered Salem, but Salem soon forgot them. He began to move out of habit and habit alone.

Salem enjoyed writing, but soon his words began to sound like a broken instrument, spread across everything, never apologizing for being broken, reckless or moving. A small entry – “Once, we reached for the rain” – is Salem’s last-known piece of writing. The rest consists of small diatribes or long meditations, sometimes bordering on obsession, always flirting with absurdity.

Salem always looked west to watch the stars rise. He developed a small affinity for astronomy when he was younger, which was a hobby he maintained, however passively, until his death. He never memorized constellations and was careful not to mention his enthusiasm for fear someone would ask him to recite the night’s sky. For some time he traveled with a pair of binoculars, the same binoculars his father used during the war, but these too quickly became relics, and so he forgot them.

Consistently, Salem returned to art. For him, art was an anxiety-driven experience. “Where in life we do all we can to avoid anxiety,” Morton Feldman wrote, “in art we must pursue it.” Feldman was perhaps Salem’s favorite composer and many of the compositions Salem left behind were minor variations on Feldman’s music. These variations only deviated from the original score because Salem wrote them down by ear, as an exercise, and not as an act of creation.

There was no funeral in his honor, per se, though a priest did offer a brief and uncertain eulogy as Salem rested in a closed casket, buried in the back of a church he never once attended and grieved only by the woman on the corner who once sold him flowers. Salem had no choice but to submit to his epitaph: “The soul flies east to rise with the Sun.”