Years after fighting weight issues in elementary school, McCormick senior Dennis Ai developed a video game app that won him $10,000 presented by Newark Mayor Cory Booker, a hug from Michelle Obama and exposure to hundreds of stakeholders and consultants during a summit in Washington, D.C.

As an overweight child, Ai often felt singled out. But in sixth grade, he began to focus on eating healthier and exercising.

“I definitely feel like I have a responsibility to try to do something for kids who are going through the same thing I went through,” he says.

Last summer, Ai and Weinberg sophomore Victor Quan researched childhood obesity and the frequency with which children play video games. The two decided to create JiveHealth, a game designed to prevent obesity by encouraging healthier eating habits.

The task was to create a game that appeals to children while benefitting their health. Set for a June 15 release on the iOS app store, JiveHealth plays like a backwards Temple Run with an Angry Birds-style slingshot maneuver, says McCormick sophomore Christian Yenko, the team’s software engineer.

In each level, players must collect recipe ingredients that they can then use to upgrade their characters. Some ingredients are purposely unavailable in the game so that players must find them in real life, encouraging them to seek out healthy food. They must upload photos of the items, which are then digitized for the game.

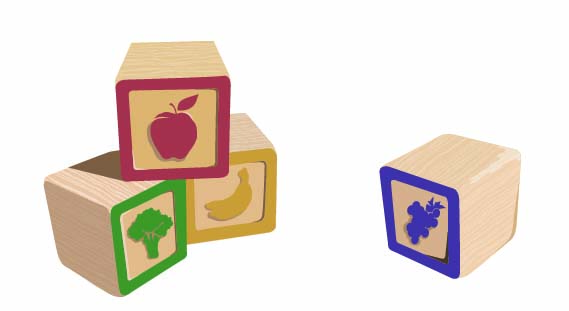

The app identifies an object in a picture and makes it virtual, using an algorithm that analyzes the image. As of now, it can discriminate between an apple and a banana, but Yenko would eventually like the app to be able to tell the difference between an apple and a photo of one, so that players won’t be able to cheat by snapping a picture from a Google search.

Yenko is working on the algorithm with McCormick professor Oliver Cossairt in an independent study, while Ai and other members of JiveHealth’s five-person team work on other aspects of the game. Cossairt says the object-recognition algorithm is a valuable component of the game, because object recognition remains a problem in computer vision. It is difficult for a computer to identify where one object ends and another begins. JiveHealth is trying to ease the problem by controlling the way pictures are taken, so that only one object is in the camera’s field of view at a time. The pair is currently focusing on 2-D images but has not yet discussed how to avoid the types of cheating Yenko described.

Quan and Ai used ideas from discussions with potential consumers and professors to develop JiveHealth. They also created a research study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board, but they did not carry it out due to a lack of time and money.

Although Quan is no longer involved in the project due to time constraints, he says the study would have lent the app more credibility. “People wouldn’t be as convinced that the game would be able to help kids be healthier without scientific proof,” he says.

But Quan is optimistic about JiveHealth’s success. “They’re actually making something that would possibly make a difference in the world.”