Each year on the second day of February, many Americans elect to receive climate data from a small furry rodent (ICYMI: Punxsutawney is calling for 6 more weeks of winter). On this Groundhog Day, however, One Book One Northwestern provided an opportunity for students, faculty and community members to hear from a much more reputable source.

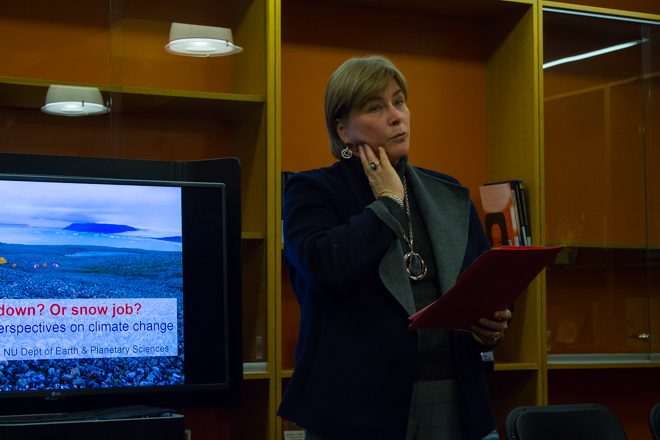

Earth and Planetary Sciences Assistant Professor and climate scientist Yarrow Axford led a presentation and discussion on climate change in Main Library Thursday in an event sponsored by One Book and the University Library.

Nancy Cuniff, the director of One Book One Northwestern, began the event by introducing Axford, relating her work in the field of climate science to Nate Silver’s "The Signal and the Noise," this year’s One Book.

Axford then stepped up to the lectern, preceding her presentation of data and findings with the idea that climate science isn’t an inaccessible, distant field of study, but rather one that applies to the lives of every person on earth.

“You really don’t have to look at data to see that the climate is changing,” Axford said.

After discussing some social and geopolitical changes that can result from the changing climate, Axford delved into a discussion of her research.

A geologist by training, Axford’s research focuses on using sediments at the bottom of lakes and the fossil evidence found in those sediments as indicators of climate over thousands of years. Audience members enjoyed seeing the adventurous lengths Axford has taken to get to research sites in the remote arctic, flying on military airplanes and small helicopters to reach pristine lakes in Greenland and Canada.

Presenting her findings, Axford showed how over the past 2,000 years, there was a general cooling trend up until the 20th century, when the pattern changed and temperatures rose rapidly.

“It’s not about what year is the hottest, it’s about the long term,” Axford said, in reference to 2016 being the warmest year since global climate data began being accurately recorded.

Axford also displayed data from other fields of study, including carbon dioxide records which indicate that the current levels of atmospheric CO2 are far higher than at any point in the past 2.5 million years, and scientific papers describing the “greenhouse effect” – a phenomenon in which certain atmospheric gases trap in heat from the sun and create global warming – dating back to 1896.

Although Axford pointed out that 97 percent of actively publishing climate scientists agree that human activity is a significant factor in changing mean global temperatures, she made it clear that there is no way of knowing exactly what to expect in coming years, saying, “there’s a lot of uncertainty about how this will unfold in the future.”

Following her presentation, audience members asked questions covering topics including details about research, predictions for the future and clarifications of facts.

Weinberg junior Cari Schuette said she had spoken to Axford before and knew of her research, but came because as an earth and planetary sciences major focusing on climate science, she was interested in the topic.

“It was interesting to hear what other people had to say and what questions people had,” Schuette said, “especially with the question about the next four years and what will come of that.”

The question Schuette referenced came from an audience member curious about how the new administration of President Trump, which has so far been less-than-friendly to environmental organizations like the EPA, might affect the research done by Axford and scientists like her, which is funded by the federal government through the National Science Foundation.

Although Axford said that she will probably be okay because, as she put it, the rocks she studies will still be there in four years, she expressed worry in other climate science studies going forward.

“I’m very pessimistic about research like mine in the future,” Axford said.