Venezuela, once the richest country in Latin America, finds itself burdened by one of the biggest financial and political crises in modern day history. News of corrupt elections, chaos and strife permeate America’s mass media, and through it all circulates a central word: dictator.

A march near el Palacio de Justicia de Maracaibo in Venezuela.

Photo courtesy of María Alejandra Mora via Creative Commons

But perhaps we should question why the word “dictator” is an oversight, and very possibly wrong.

A Google image search of 'Venezuelan dictator'.

Photo by Audrey Valbuena / North by Northwestern

“To start with the word ‘dictatorship’ is to completely disregard the history of the Bolivarian Project and the history of Chavismo to which Maduro is just a – or tries – to be a continuation,” said Lina Britto, an assistant professor in Northwestern's history department, in criticism of American mass media. “This discourse about dictatorship has prevented us really from understanding what’s going on because it has deep roots, and roots that legitimize what they were trying to do, even if they failed in many aspects.”

For those outside Venezuela, and for much of the English-speaking world, the assumption of a Venezuelan dictator has rested at the center of the crisis. The word ‘dictator’ absolves the situation of any foundation in democracy. But Chavez’s rule was very much rooted in democratic principles with the Bolivarian Project, an effort to turn Venezuela into a welfare state and bring the common people back into politics.

But at some point, these ideals broke down. With the crash of the oil market on which Venezuela’s economy was founded, the nation spiraled into crisis: With no funding, the administration could not provide social programs, and so increasingly became larger and more corrupt in an effort to sustain a semblance of what it once was.

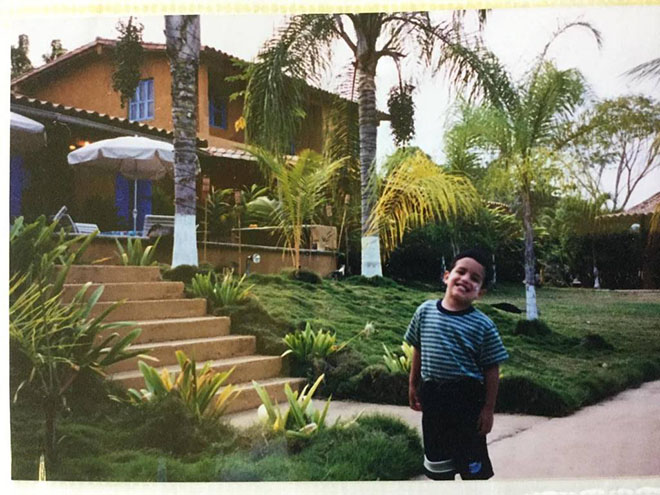

“Even at my young age I could start to see it,” Weinberg junior Carlos Belardi said of his childhood days in Venezuela. Though Belardi left the country at the age of 7, he said, “I could see it with little things about how my parents would just always be talking about Hugo Chavez, and how we had to take so many precautionary measures because crime was starting to increase a lot.”

Since Belardi left Caracas in 2003, crime in Venezuela has only continued to increase. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has concluded that the situation is comprised of “widespread and systematic use of excessive force,” according to “Venezuela: Perspectives from the South.” Constitutional changes and new elections are constantly challenged: When a recent election came out in favor of Maduro, the “opposition coalition refused to recognise the results of Sunday's gubernatorial elections,” as stated in Al Jazeera.

“I’m not saying that Nicolas Maduro’s presidency and administration has not engaged in very authoritarian practices – it has. We are in a moment of incredible uncertainty and darkness, where nothing is really clear,” Britto said. “The few Venezuelan people that I know and have contact with are very pessimistic, and are very worried.”

The idea of the welfare state has irrevocably broken down. Maduro is not Chavez, and does not have the leadership capacity to rally the nation into safety. As stated in the Guardian, he “lacks the charisma of his predecessor, has seen his approval ratings plunge amid widespread food shortages and triple-digit inflation.” Instead of focusing on administrative needs and providing his people with the basic needs – food, shelter, security – Maduro’s administration has double-downed focus on the opposition, seeking to extinguish any threat to power.

“My family is still in Venezuela, and I constantly fear for them,” said McCormick junior Armando Márquez, who lived in Caracas, Venezuela, until he moved to Miami when he was 4. “Many members of my family have been subjected to some form of violence. One of my cousins has been held hostage, and my aunt has been robbed at gunpoint.”

In these moments of strife, it is easy for American media outlets to villainize the situation by naming something – a dictatorship – deeply opposed to the values this country holds. It’s easy to write off the terror of the situation in a system of government than to acknowledge that this breakdown of power is something that, with similar circumstances, could very well happened here.

Venezuela is not just a place mentioned in the news – it’s a home to many, including a number of students and a home that deserves a fairer assessment than what the mass media portrays. It does not simply follow the trope of dictatorship gone wrong: There is a much more complex history, rich with the values of the people who are now fighting to save their home.

“It is sad to see the country I spent a decent chunk of my childhood in just fall apart like this,” Belardi said. “I have a lot of good memories from living in Venezuela, but the places where those memories were made either don’t exist anymore or are just empty shells of what they used to be.”

Weinberg junior Carlos Belardi at age 5 in Valencia, Venezuela.

Photo courtesy of Carlos Belardi