You may never look at a fruit fly’s bright red eyes the same way again. For a team of Northwestern researchers, studying the developing eyes of fruit flies unlocked new ways of looking at cancer causes and treatment.

“It is potentially pointing the way to new kinds of therapies,” said molecular biology professor Richard Carthew.

Carthew said the project was six to seven years in the making, culminating into a study published on Jan. 14. It was a team effort that included him, chemical and biological engineering professor Luís Amaral, interdisciplinary biological sciences Ph.D. candidate Nicolás Peláez and University of Chicago researchers.

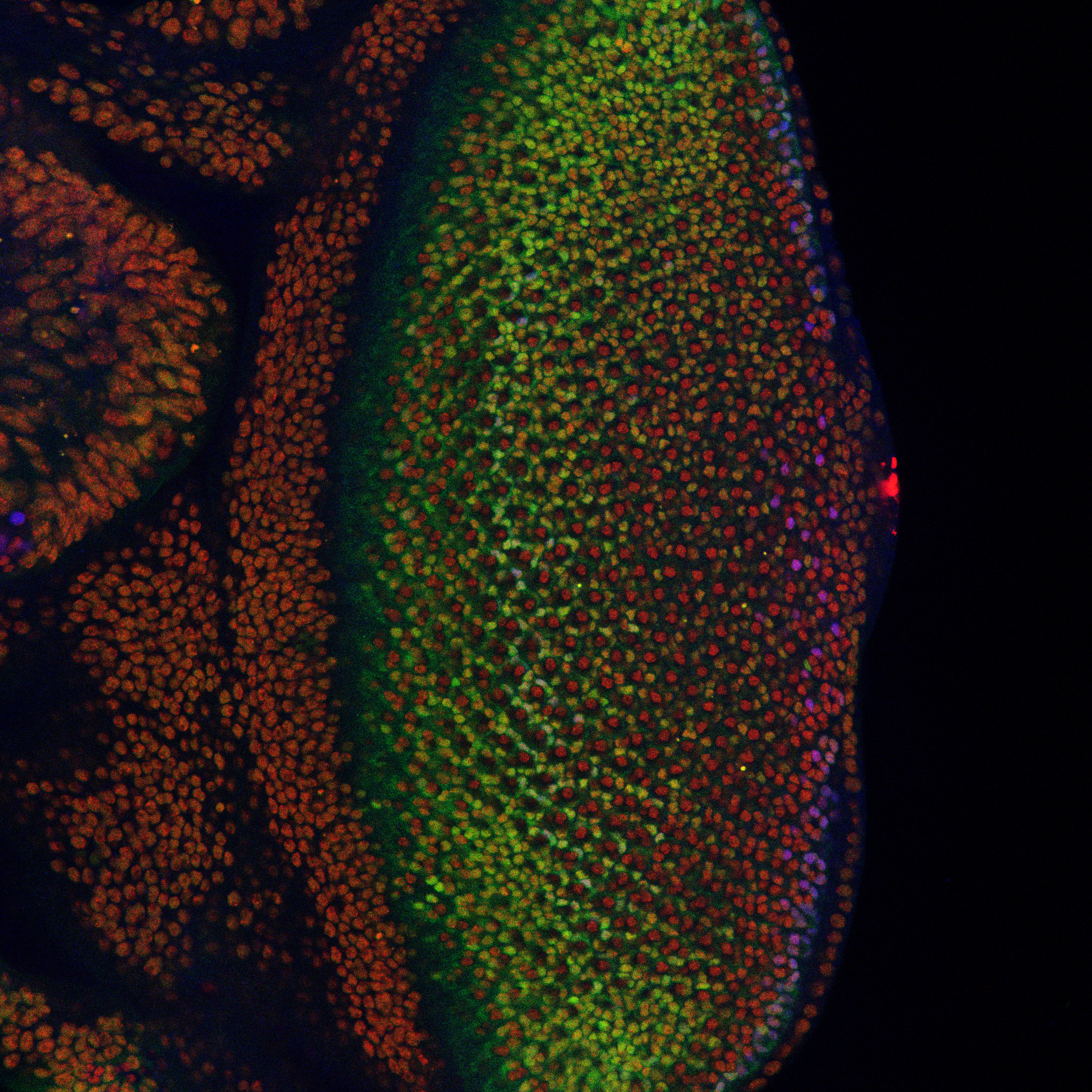

The team studied fruit fly eyes because they include many specialized cells, like light-sensing neurons and cone cells. Flies and humans also have many of the same cancer-causing genes in common.

Peláez studied not the process of cancer directly, but rather normal cell behavior in the eye.

“We focus on when things go wrong,” Carthew said. “But in order to understand how things go wrong, we have to understand how things work.”

Every cell in the body starts out as a stem-cell. When cells switch from a stem-like state to a specialized state, protein molecule levels will fluctuate wildly. If everything goes right, the cell will change to a stable state. But if the molecules keep fluctuating and the cell does not change to a stable state, this can lead to cancer.

It’s like being in a valley, Carthew says. In a valley, you’re on stable ground, and you have to climb over a ridge to reach another valley. When the protein molecules fluctuate, it’s like being on top of an unstable ridge. If you don’t get off the ridge, this can be dangerous. For cells, this means staying in that in-between state.

“This might be more of what cancer is like,” Carthew said. “In cancer, when cells are in an in-between state, these things (cells) are in an unstable zombie-like state. This makes it hard to control.”

Peláez focused on two protein molecules: HER2, which is commonly mutated in breast cancer, and TEL1, which is commonly mutated in leukemia.

This research does provide potential for new types of therapies, although the process from discovery to therapy is long. However, this discovery allows researchers to look at treating cancer with a new lens. Currently, treatment focuses on reducing cancer levels in the body.

“We’re suggesting it’s not just the levels or the amount, but how stable it is,” Carthew said. “That could be an effective way to treat cancer.”

Researchers could look into developing drugs or treatments that not only change the levels, but also stabilize the cancer and stop the fluctuating. The research came in the same month President Barack Obama announced the establishment of a task force to fund cancer research.

Carthew said that the budget increase for the National Institute of Health is also encouraging, as funding for the institute has declined in the past.

“It’s had a negative impact in biomedical research, so it’s very heartening to most people that Obama invested in National Institute of Health, hopefully it will continue going forward,” Carthew said.

The team plans to continue with this research.

“It appears that this is a pretty common phenomenon,” Carthew said. “We hope that we can translate this discovery to early detection or prevention or treatment to various kinds of cancer.”