“It’s like a legend,” Weinberg sophomore Jamal Julien says, and it begins in the fall of 1966, at the dorms and on the sidewalks lining Sheridan road, with 54 students singled out solely by the color of their skin. And, as has been the case for much of American history, that was enough.

It was the height of the Civil Rights Era, the year Martin Luther King moved to Chicago to launch the Open Housing Movement and Huey P Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panthers. Federal policy barred discrimination for the first time and Northwestern, like other elite universities, had begun opening its doors to Black students. It was supposed to be Brown v. Board brought to the college campus, W.E.B. Du Bois’ integration dream realized.

It’s not clear when these 54 students realized something was wrong, that the University was promoting what they would later call a “great white father image,” both racist in its conception and failing in its practice. Certainly, it was well before the administration realized, before the students made them realize in 1968 with a sit-in that would send the University and the national press into a frenzy and force Northwestern to make unprecedented concessions.

For Victor Goode (CAS ‘70), it was that first day in the fall of 1966, when he saw he was one of the only Black faces in a sea of white ones. For anyone who took more convincing, students from the time recall the fraternity brothers throwing beer bottles, “plantation parties” with students in blackface, fights outside Sargent and in the dorm rooms, the mere sight of a group of Black students sending white students into alarm.

In 2015, students at colleges across the country protested for racial justice at levels not seen in nearly half a century. At Northwestern, the protest launched after the administration, as president of Northwestern University Black Alumni Association Jeffrey Sterling wrote in a letter to the editor of The Daily Northwestern, chose “to abrogate the May 4th agreement” of 1968. On a superficial level, Northwestern had moved Department of Campus Inclusion Community offices from Scott Hall on 601 University Pace to the Black House on 1914 Sheridan Road.

But for Black students and alumni, the office move was the last in a slew of violations to the Black House. Signed on the 38th hour of the sit-in, the agreement was, as Sterling wrote, “a covenant without an expiration date.” The Black House was its centerpiece, functioning not only as a linchpin of negotiations – as a necessary demand with clear and important benefits for Black students – but as a sort of monument, validating Black presence on campus.

In the last ten years, students say the monument has begun to fall into disrepair. Water fountains have broken, the computers have become outmoded and the basement has been rendered unusable.

A year after the protests, in September 2016, a University task force announced what students had long been saying: that Northwestern is an “exhausting” environment for many Black students. The fight continued, in part on the streets, and in part through an ASG campaign, arguably the first one to stand on a platform almost exclusively focused on voicing the needs of marginalized students.

What follows is NBN’s attempt to understand the factors leading up to and the aftermath of 1960s protest and today’s movement, in hopes that it can offer a clue to the question hanging over universities nationwide: Where will the new protests lead?

Before Goode stepped foot on campus in 1966, no one told him what Northwestern was like.

No one told him that he would be one of about 80 Black undergraduates on a campus of about 8,000. That realization hit on move-in day as he walked down Sheridan Road for the first time, the only Black face in a mile-long strip bustling with students.

“There are a lot of students around, folks getting set up,” Goode said, “And I’m thinking to myself, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’”

Goode had unwittingly stepped into the the University’s first experiment with integration. That year, Northwestern enrolled 54 Black freshmen, a significant increase from 1965’s 26 freshmen and the mere handful that had been on campus in years prior. Coming to a university barely three miles north of Chicago, Goode expected, at minimum, a modest Black presence, given the historically high Black population in the metropolitan area. Instead, he rejoiced that evening when he finally found two other Black students.

It wasn’t just that there were few Black students – many of the white students were openly hostile.

The moment the first sizeable wave of Black students made it to campus in 1966, several white women who had been assigned Black roommates demanded room changes. Northwestern complied, but didn’t do the same for Black students who asked for a similar change.

Their reasoning? If Black students roomed together, white students couldn’t learn from them.

“We didn’t want to be brought there to be Guinea pigs,” said John Bracey, then a graduate student and one of the leaders of the 1968 protests.

Vernon Ford (SESP ’68) recalled Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) parading down Sheridan Road in blackface one evening. Later that night, a few brothers encountered a Black female student and touched her inappropriately. The brothers later apologized to the girl in a ceremony, after Ford and another Black graduate student accompanied the girl to the dean’s office.

The Black students were inundated with insensitive questions and offensive comments. They were harassed for playing Motown and other music genres that came out of Black culture, said Kathryn Ogletree (CAS ‘69), one of the student activists. One night, white students threw beer bottles at Black students as they walked home.

“Our humanity was not taken into account,” Ogletree said.

The tipping point came in April of 1968, when Martin Luther King was shot and killed on a hotel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee.

By then, Northwestern’s Black population had grown to about 120 students and, influenced by the national Civil Rights Movement, they had begun to organize. Grad students formed the Afro-American student union, and in the fall of 1967, undergrads created For Members Only, the group that continues to serve as the base for racial justice organizing and a safe space for Black students on a predominantly white campus.

Goode and other friends traveled to New York and met with the Black student union at Columbia University where they found that Black students at other schools were facing the same problems.

“By the time we got from ’66 to the spring of 1968, the number of incidences had built up,” Goode said. “The unresponsiveness from the University had grated on people, the idea that we were to remain on campus as a voiceless, invisible minority, somehow melding into the broader white university was something we knew would not happen and could not happen.”

After King’s assassination, protests swept cities nationwide, and the students felt an obligation to join, Ogletree said.

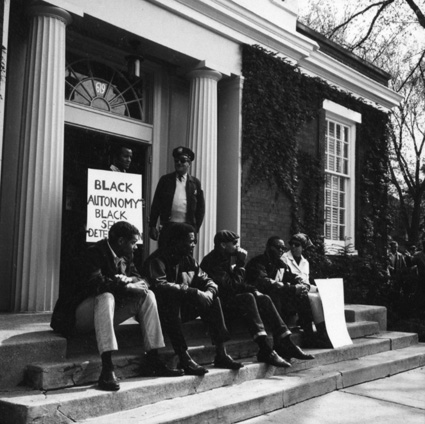

On April 8, four days after the assassination, 325 Northwestern students demonstrated outside of Rebecca Crown Center to demand the University pressure Evanston to pass an anti-discrimination, open occupancy Ordinance. Fourteen days later, James Turner (CAS ‘69), president of the Afro-American student union, submitted a list of demands to the University.

After then-University President Roscoe Miller issued a statement condemning racism but did not comply with most of the demands, Turner held a press conference on May 2 with a “last time” statement and demands. The University responded with a request for a meeting but the students rejected it, instead demanding immediate action.

That night, Bracey said, the students met to plan the protest. With the University on red alert for a demonstration, student activists ensured no one knew enough information to blow the entire operation. Student leaders told people it would happen at Rebecca Crown, the administration building. It was a decoy.

On Friday, at around 7:00 a.m., about 100 Black students hid in an alley across the street from the Bursar’s Office at 619 Clark Street. Meanwhile, Bracey said, University guards patrolled the administration building about 100 yards away. One student got in by telling the Bursar’s Office's lone security guard he needed to drop off a form, while several other students started a diversion at Rebecca Crown. When the guard went to aid the ones at Rebecca Crown, 14 protesters rushed in and secured the building. The rest soon followed suit.

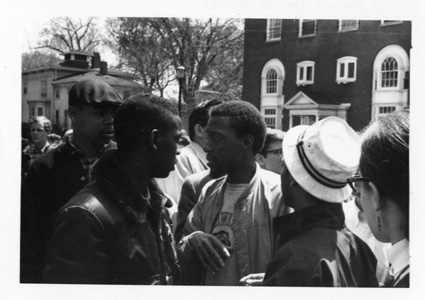

Ogletree, Bracey and Turner started what would become a 38-hour sit-in. White, Hispanic and Middle Eastern students surrounded the building to defend the activists from potential police violence, and 30 more occupied the office of Roland Hinz, vice president and dean of students. The white students were allies, then-protestor Wayne Watson said, but the Hispanic and Middle Eastern students saw the protest as their struggle, too.

Ten days earlier, on April 23, police had been called in to end student protests at Columbia University. Law enforcement barrelled in with tear gas, violently suppressing the action.

“There was a terrific fear that this sit-in would end violently,” said Tom England (Medill ‘69), a white student activist at the time. “We made sure that if the cops took violent action against Black students, they would have to do it against white students, as well.”

Receiving news of the Northwestern protest at a board meeting, President Miller, told Vice President of Planning and Development Franklin M. Kreml, “Throw the recalcitrants out, call the cops and throw them in jail.”

If another administrator had been on the other end of the phone with Miller, Northwestern might have become just like Columbia, remembered for being another site of the police-protester clashes that marked much of the 1960s. But, in addition to the allies who surrounded the building, the protesters also had Kreml, who had seen what “calling the cops” could do to a peaceful situation during his first career as a police officer. He cautioned Miller to pursue a reconciliatory approach, convincing him to invite 10 Black students for what would become a marathon negotiation.

On May 4, after the students had occupied the building for 38 hours, Northwestern released a statement in which the University recognized it was part of the “white establishment” that “must share responsibility for the continuance over many past years of these racist attitudes.” And they assented to nearly a dozen of the students' demands.

The University created student-faculty committees to recruit professors and students, Black living spaces students could opt-in to, paved the way for the beginning of one of the nation’s first African-American Studies Department, and took a bolder stand for open occupancy in Evanston.

“We got pretty much everything we asked for,” Bracey said. “We got the Black House.”

You’re unlikely to hear this story mentioned on a campus tour or University promotional material. Nearly fifty years later, however, there’s only one place the story is consistently told: a Wildcat Welcome orientation night for Black and Latinx students. There, it’s the centerpiece of the evening, said Bria Royal (Communication ’16).

Many who didn’t learn at the orientation discovered the story at the listening sessions for the Black House in November of 2015. For some, it became a motivator, a guiding tale of what a small group of dedicated students could accomplish.

“It’s like how we view the Founding Fathers of America,” Julien said. “It started social justice activism at Northwestern … it’s what grounds us.”

There were differences between the the issues students in the 1960s faced and what students now deal with, of course – important ones – but the parallels were enough to inspire, and despite a half-century gap, the demands echo each other.

The 1968 protestors’ first policy demand was increased financial aid and admissions for Black students. In this, they were remarkably successful, helping cement the affirmative action and financial aid policies that would shape the school for a generation. By 1973, the percentage of Black students at Northwestern had risen to 10 percent of the student population.

But over the last couple decades, the gains of the May 4th agreement have dissolved. While the number of Latinx and Asian American students on campus has surged over the past ten years, the number of Black students has been roughly stagnant at about five percent since 1999, less than half the national Black population, which hovers near 13 percent.

“The protesters have opened our eyes to the fact that we’ve reversed so many gains of the Civil Rights era,” Biondi said.

The deteriorating condition of the Black House and administrators’ decision to reallocate its space without consulting students, was for many symptomatic of larger neglect of minority students on campus. Nearly 50 years after students demanded the house as a haven on a hostile campus, Royal said it’s still one of the only places she feels fully safe.

“The part [of Northwestern] that was violent towards me and my identity was mostly experienced in classes where I wasn’t around the Black community,” Royal said, citing incidences where professors asked her to give the “Black Perspective,” on an issue.

Despite efforts to hire professors of color in the 1990s, faculty diversity has not kept up with the diversity of the student body, and students complain of instructors making culturally or racially insensitive remarks.

“I hate to say it, but things really haven’t changed that much,” said Watson, who recently retired from his role as president of Chicago State University. “The issues are the same, it’s just the degree of impact. Instead of going against a headwind of 190 degrees, we’re now going headwind of 185 degrees or 186 degrees.”

In the same way the Civil Rights Movement influenced the ‘60s student-activists, the new protests grew in part out of the Black Lives Matter movement. For Royal, the viral videos of Black men gunned down by police challenged her entire sense of justice and her trust in the institutions she had been told would bring it.

“[The protests are about something] bigger than us,” said Thelma Godslaw (Weinberg ‘16). “It’s the history of the United States, of racism, of what Black Lives Matter is bringing to the forefront of people’s conscious.”

Godslaw, however, dwells on the stark differences between today and yesteryear. Today, the movement is more intersectional, she said. She and Biondi noted the coalition is broader, both in terms of the movement's influence and the identities it touches. Students are now fighting for Indigenous Studies classes, rather than just African-American Studies. Where the ‘60s activists fought discrimination in Evanston and advocated for Black students in Chicago Public Schools movements, today movements such as the private prison divestment campaign, Unshackle NU, seek to curb injustice nationwide.

Most of the fruit of the protests have yet to be realized. The University remains invested in private prison companies and admission rates for Black students remain stagnant, but Northwestern promised to preserve and improve the Black House, announced a plan for an Indigenous Studies Research Center, and, after a 20-year-fight, created the Asian American studies major.

“What we can learn from the ‘60s is that these protests do have an impact,” Biondi said, “Whether it’s durable for the long run is another question.”

Last spring, SESP Senior Christina Cilento and Weinberg Junior Macs Vinson rode that wave of activism into office as ASG president and vice president on a campaign centered around marginalized students, offering another pressure point on the University, and serving as an experiment in what an activist student government can accomplish.

The University has offered modicums of recognition of the student demands, as the 1968 administration did when the sit-in started, with University President Morton Schapiro writing op-eds in major publications in praise of student activism. But with few of the protesters’ demands met and the University continuing to shut down safe spaces, like their elimination of counseling from the Women’s Center, students are growing angry, Cilento said.

“It’s a matter of reminding them that the demands are not going away,” Cilento said, noting “there’s always the chance for more protests.”

And so the fight goes on and the protests continue: for trigger warnings and culture competency classes, for Black professors and prison divestment, for indigenous studies, minority STEM support and a sanctuary campus for undocumented students threatened by President Donald Trump’s mass deportation plan.

These latter protests have been particularly successful, prompting Schapiro to formally announce the school opposed Trump’s Muslim ban and would not give student immigration data to the federal government. On Wednesday, Feb. 1, the first protest appeared: well over a hundred gathered at the Multicultural Student Center, chanting “No papers, no fear, immigrants are welcome here” and “no ban, no registry, fuck white supremacy.”

And if the Bursar’s Office sit-in is not a map to success, it’s a marker on the trail, a reminder that someone, once, walked this path and came out on the other side.

“It’s become clear to me that there’s more to be won and more work to be done,” Godslaw said. “And I think the people who are taking up that work right now are doing it slightly differently and intentionally but it’s still the movement for justice, it’s still the movement for change, it’s still wanting more.”

“So, is it new?” she asked. “It’s different, but I wouldn’t say it’s new. It’s a continuation, it’s building off of history.”