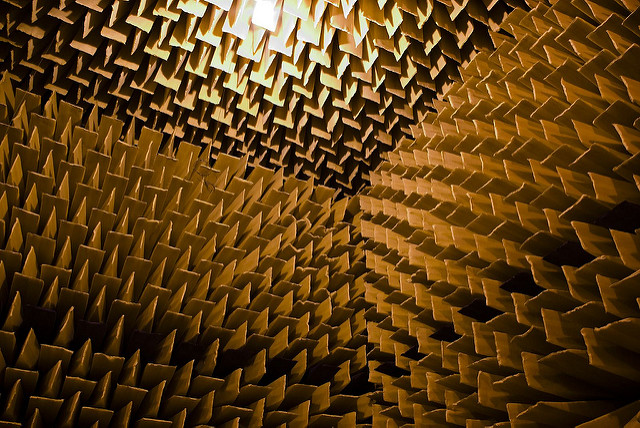

In January, I had the opportunity to visit an anechoic chamber. The anechoic (literally an-echoic, or anti-echo) chamber uses dense soundproofing to eliminate room tone within its walls, creating absolute (or near-absolute) silence. Coupled with the lights being shut off, the resulting sensory deprivation has been known to induce mild hallucinations, with the world’s quietest chamber registering in negative decibels. My own description of the chamber and my experience within its walls is woefully inadequate, but John Cage, the master of engaging critically with silence, sums up the experience more eloquently than I could ever reach, describing the ways in which he heard his own body operating as all other sound disappeared. Below are my reflections after spending only five minutes in the chamber, and the experience’s relation to our modern media environment, one dictated by technologies more potentially alienating than ever before.

Leaving the chamber, all sound slowly took meaning again, its discrete variations more noticeable than before. At a construction site adjacent to the building, the distinct purr of two different machines marked themselves in succession, their subtle vibrations rendered in stark contrast to my newly attuned ears.

Returning from this experience of complete isolation made me most appreciate one simple fact: that we may all lay claim to our immediate surroundings, those physical spaces that we come to cohabit. It’s the quiet buzzing from the fridge, a gentle tap of a leaky faucet, the distant hum of traffic – all remain knowable to all of us sharing one physical space, a necessary commonality grounding us in a shared sensory experience. Though we all still take in our surroundings and the broader world subjectively, to me there’s a real comfort knowing one can sense a physical space in a more or less stable manner, in accordance with the unspoken agreement of others.

Perhaps that is what most scares me about the changing landscape of our technological lives: more so than any single form of media that has ever previously existed, smartphones are by far the most subjective, each unique device customized for individual use only. Even when a TV lulls one or a collective into a state of mediated trance, it’s still a shared mediation, shared equitably with those others in the path of the same screen. The phone (and, by extension, social media) is an inherently personal platform. Even when somebody else looks at my phone, they examine something entirely alien, a machine purposed for my needs exclusively.

The sense of alienation only grows on social media. I dare you to scroll through a friend’s newsfeed. Its appearance is at once intimately familiar, not a notification or message icon or chat window out of place. But quickly, you begin to lose a grasp on what you’re seeing, the feed a flurry of unfamiliar faces exposing a window into lives unknown and unknowable.

As we allow ourselves to devote greater energies to these platforms, we structure ourselves to accommodate them into our bigger, fuller physical worlds. In a room of friends, each firmly attached to this attractive illusion, we lose our ability to attune ourselves to what should come easily to us, namely that physical setting that feels increasingly archaic. A sudden noise, a flash of light – did everybody see that, hear that? If a tree falls in the woods, and nobody is there to capture its descent and instantly upload it to Snapchat, did the tree really fall?

That’s what so saddened me about leaving the chamber. As those of us in the class came back to reality, returning to the land of sensation, about half of the group grabbed their cell phones, plunging back into their own little world without thought. Those five minutes in the chamber were some of the most isolating moments of my life – and yet, I felt more isolated in that brief elevator ride, watching my peers fall into a rabbit hole of technology instead of appreciating the small joys of regaining a physical sense of their surroundings.

It may be a fool’s errand to suggest that one live a life largely disconnected from media, and saying so today is obviously deeply unrealistic. But, as I’ve learned from losing my senses (even for five minutes), there is value in aspiring to that as a goal. You will fail quickly, and often. Not all use of media is unwise, or unpleasant, or alienating. But the one force that we can all use to grasp at the physical world is our bodies, each fantastically equipped to enjoy the sensory pleasures of our stimulating world.

I think one of the most valuable ways to reflect on the power of the body as a mediating force is to think of the word “immediate.” We hear it so often today, now that communication has sped up to the point of conceivably putting anyone into contact with another in an instant. But as we unpack the word, we see something different. One dictionary definition is “without intervening medium or agent; direct.” At times, perhaps in moments of loneliness or boredom, one may turn to the supposed immediacy of technology. And yet, such an act places something between people, at times a necessary compromise when they’re far away, but still a behavior that will divorce us from our environment.

Still, these mediating forces will certainly remain an ongoing aspect of our lives. And yet, we run the risk of losing our most tangible form of immediacy, that which we can see and hear and touch in our own small corner of the universe. Ultimately, if it’s immediacy that most concerns us, we may lose sight of what that word can really mean. Look up from your phone as you read these words, and observe those people and the environment surrounding you. That is your immediacy. Don’t lose it.