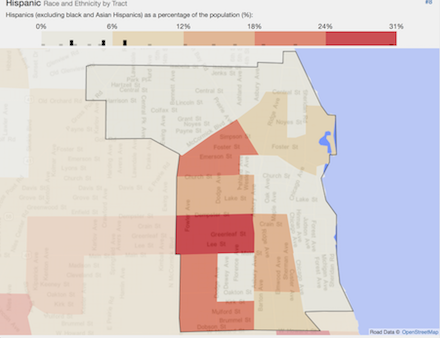

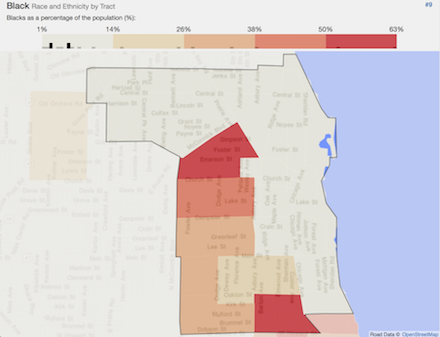

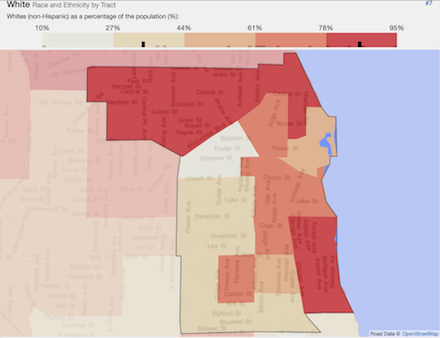

Graphic courtesy of Statistical Atlas

When people think of Chicago, they think of skyscrapers, Lake Michigan, the hustle and bustle and the South Side, but advocates like Andre “Add-2” Daniels and Maria Hadden focus on something that many fail to notice: housing discrimination. Chicago is the third-most segregated city in the United States, according to the Chicago Tribune, and the past and present effects of structural inequalities continue to haunt Chicago.

Members of the Northwestern community and beyond came to the McCormick Foundation Center on Jan. 19 to take part in “Inside Chicago” as part of Northwestern’s commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., which focused on Chicago’s structural inequalities through a discussion with two local community leaders. “Inside Chicago” was part of a multiday MLK Arts Festival presented by Vertigo Productions, which featured two segments of the documentary “Inside Chicago.” The arts festival varied from an open mic to multiple staged readings, but with one common goal: to offer programming that highlights and celebrates the voices of NU’s Black students.

The discussion was moderated by Communication senior Kori Alston, who is president of Vertigo Productions, and it featured Daniels and Hadden. Daniels, a West Englewood native and self-described M.C. and mentor runs Haven Studios, a music mentoring program for South Side youth. Hadden, who has lived in Chicago for 13 years and does work related to civic engagement, is a former member of the Black Youth Project 100, where she is a current board member and alumni chair.

The video segments and discussion centered around historic sources of structural inequality in Chicago, analyzing practices like redlining – the practice of denying services to residents of certain areas based on their racial or ethnic makeup – but it also made clear that “the scars of a segregated city run deep,” and they’re far from over.

Hadden spoke to the changing racial makeup of Chicago, saying that people of color are leaving Chicago, and white people are increasingly moving in.

“So we’re getting in our more densely populated city more people from outside of the city,” Hadden said. “Looking at the changes over time, and going from the Jim Crow era redlining, looking at all of these practices and how it’s influenced things, I feel like we’re also experiencing another 10- or 20-year period of trends in who’s living here, who’s allowed to live here.”

Daniels brought up the importance of realizing how subliminal Chicago’s racially divided housing is. As someone who was born and raised in Auburn Gresham, Daniels has experienced a demographic shift in his own neighborhood.

“We didn’t realize how subliminal that [racial division] was to show us how divided we are," Daniels said. "We’re the third biggest city, but yet the idea of being integrated is foreign. We have these different corners, and we’ll just stay there.”

When asked about how the Trump administration has changed Chicago, he didn’t speak about Trump’s words or legislative actions; Daniels spoke about the changes in the art of the children he mentors.

“Lately I’ve been seeing and hearing a lot of art that is a little bit more fearful, but also a little bit more protective, as if they’re starting to fully understand their place in the world, and to understand if something is under attack, you protect it through whichever form of protection you have,” he said.

Daniels also stressed the importance of diversifying coverage about Chicago, calling on people to recognize that the South Side is far from its one-sided portrayal.

“All you hear about the South Side is violence, as if we wake up in the morning, and before we even get cereal we’re ducking bullets," Daniels said. "That’s not real. There’s plenty of people who wake up on a day-to-day basis who live absolutely normal lives. No, it is not as rampant as people make it seem.”

Medill sophomore Brandon Ford, who attended “Inside Chicago,” smiled as he remarked how the speakers made him realize the potential of young people to take on structural inequalities.

“Community members are placing their trust in young people to resist the system, resist the status quo and, in one way or another, begin to reimagine the way that we deal with issues in our communities,” he said.

Unfortunately, structural inequalities related to housing are not unique to Chicago; they also occur in Evanston. It took Evanston until 1966 to formally desegregate — more than a decade after Brown v. Board of Education. In terms of housing, Evanston is still extremely racially and economically divided. Though there has been an increase in Evanston’s Black population, from 12-18 percent according to Citylab, Black families are still living in the same parts of Evanston as the 1960s, mostly west of the tracks and in the southern end of Evanston.

In terms of academic opportunities, Evanston lags behind for its students of color. Out of Evanston Township High School’s 2015 graduating class, 92 percent of white students had taken at least one Advanced Placement test, while only 60 percent of their Latinx peers and 51 percent of their Black peers did, according to Bloomberg Newsweek.

While speaking about Evanston and racial discrimination during a June 2017 interview, former Fifth Ward Ald. Delores Holmes made a point to address Evanston’s racial divide: “We need to talk about race … We have two Evanston’s, and we always have,” Holmes said.

Juxtaposing Statistical Atlas’ data on the race and ethnicity makeup of with the map of Evanston’s wards yields visible separation of housing that varies by race. Data on the racial distribution of Evanston suggests that Holmes is right: there are two Evanstons.

Data exposes Evanston’s racially divided housing lines. According to Statistical Atlas’ racial and geographic data on Evanston, the white population concentrates in Ward 3 and Ward 7, where at least 78.5 percent of the population is white. Ward 8 and Ward 5 have populations that are 52.3 percent and 62.5 percent Black, respectively. In Ward 2, 30.54 percent of the population is Latinx, and in the area for Ward 8 and Ward 9, 18.7 percent of the population is Latinx.

Despite the many barriers to fighting back against structural inequality in Chicago and Evanston, members of the Northwestern community have the potential for political advocacy.

Jaime Dominguez, a Latino/a studies lecturer who specializes in urban politics, offered participation in advocacy organizations as a counteraction to structural inequalities on in the Evanston question, calling participation in these organizations “pivotal in terms of creating momentum.”