For LGBTQ attorney and activist Andrea Ritchie, the successful fight for gay marriage was not a seminal moment of progress. Instead, she said, the movement placed emphasis on a “respectable” middle class nuclear family, and obscured and actually hurt people already suffering far greater rates of discrimination and outright violence.

“In order to win, people engaged in this politics of respectability: ‘We're just like you, we're the friendly lesbians next door,’” Ritchie said. “The movement threw everyone who was criminalized – because they’re gender-nonconforming, because they’re Black, because they’re poor – under the bus to achieve this formal right.”

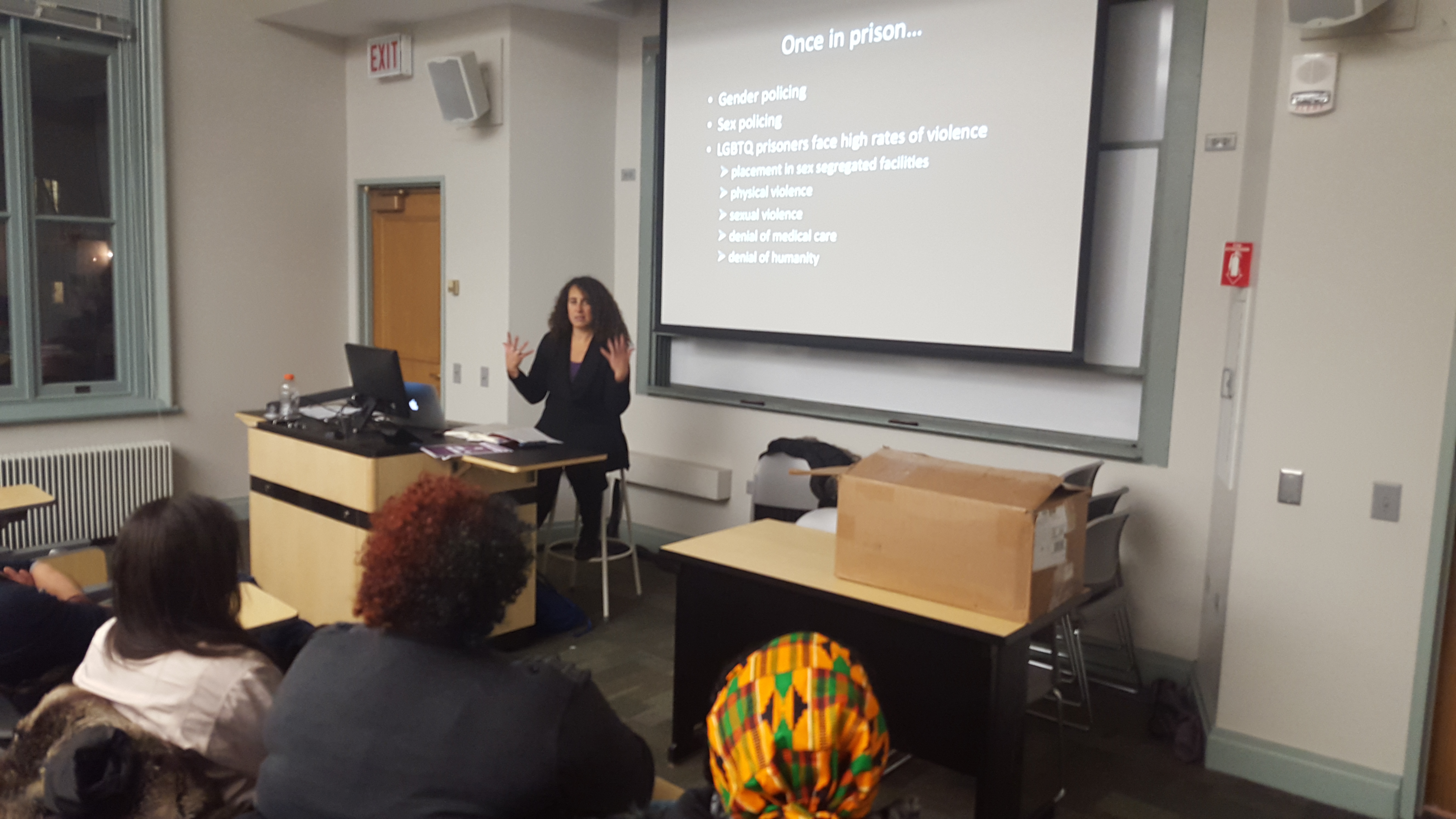

After three weeks of Unshackle NU talks on how the prison-industrial complex oppresses the impoverished and people of color, Ritchie added a third group to the disscussion at University Hall Monday night: sexual and gender minorities, or LGBTQ people of color.

Because LGBTQ people of color often fall into all three categories of race, income and sexuality, they are more likely to be imprisoned and then suffer abuse there, from runaway rates of sexual assault to poor or non-existent health care.

“[When we think of prisoners] we see hands of Black men and that’s a reality in terms of number of who’s incarcerated,” Ritchie said, showing the cover of Michelle Alexander’s award winning book, The New Jim Crow, on the screen. “But do we think about the fact that some of those Black men are gay? Do we think about the fact that some of the Black men are trans?”

2015, a year that seemed to signal growing acceptance of diverse genders and sexualities, both with the Supreme Court’s June ruling on same sex marriage and with the continued rise of public transgender personalities like Janet Mock and Caitlyn Jenner, was arguably one of the worst in recent memory for LGBTQ people of color, particularly Black trans women. At least 21 trans women were murdered, 19 of them people of color, and one of them at the hands of police. The advocacy group Black & Pink released the results of a survery, "Coming out of Concrete Closets," showing that LGBTQ prisoners experienced systemic abuse, discrimination and neglect behind the walls.

Two of the leading causes of mass incarceration, Ritchie explained, are drug crimes and quality-of-life crimes, such as sleeping outside or loitering, that police disproportionately charge homeless, Black, and low-income people with. She said high rates of poverty and sexual abuse, as well as the rejection from family many queer people of all backgrounds face, means LGBTQ people of color are significantly more likely to be homeless and susceptible to arrest for these crimes.

These general factors combine gender and sexuality to create conditions in which 47 percent of trans people of color say they were incarcerated at some point in their lives, Ritchie said. She said law enforcement will often assume trans people are prostitutes and arrest them for walking down the street. In other cases, queer people of color are arrested for using the opposite anatomical gender bathroom, she said.

Once in prison, the treatment of trans people of color is particularly harsh, Ritchie said, from sexual assault to general dehumanization. Many are stripped of their gender identity, she said; Guards shave their heads, force them to wear the undergarments of the opposite gender, and call them by their legal names of the opposite gender. According to Ritchie, officials don’t allow their partners to make visits because LGBTQ people are considered “disruptive” to the prison environment.

“It’s a stripping of humanity that happens down to the finest detail,” Ritchie said.

Trans people are often placed in prisons for the opposite sex, where they suffer disproportionate rates of sexual assault. Guards, Ritchie said, often put trans women into situations where they know they’ll be assaulted. When prisoners complain, guards often say queer people can’t be raped. Ritchie said laws designed to curb sexual violence, such as the Rape Elimination Act are often used against LGBTQ people of color, who are assumed to be perpetrators.

“The archetype of Black folks is sexual predatory, and of queer folks is sexual predatory, and when those come together,” Ritchie said, "it means that no matter what happens, you’re going to be seen as a predator in prison.”

When guards do respond, it is often by putting the trans or queer person in solitary confinement for their safety, which Ritchie described as a form of torture. Some prisoners, such as Roderick Johnson and Patrick Star, have had the support of organizations like the ACLU to file lawsuits on their behalf and force prisons to release or transfer them to safer environments, but only after prison guards ignored their repeated complaints about sexual violence.

“I knew it was already really corrupt and messed up,” Weinberg freshman Lauren Adams said after the event. “But it made it more concrete knowing the actual facts about how [queer and trans women of color] are treated.”

Moving on to solutions, Ritchie, who says as a law student she tried to get Howard University to divest from private prisons, gave advice to Unshackle NU in their fight. Activists, while attempting to abolish the prison or private prison system as a whole, need to listen to prisoners and work for their immediate needs, such as getting better medical care and the right to wear the clothing they want.

“We're about abolishing, we're about tearing [prison] down,” Ritchie said. “But right now there are people in there and they have needs.”