If the slam poetry moves you, snap your fingers. If something really really moves you, say, “Mmmm.” If it really really moves you, throw your pen toward the stage.

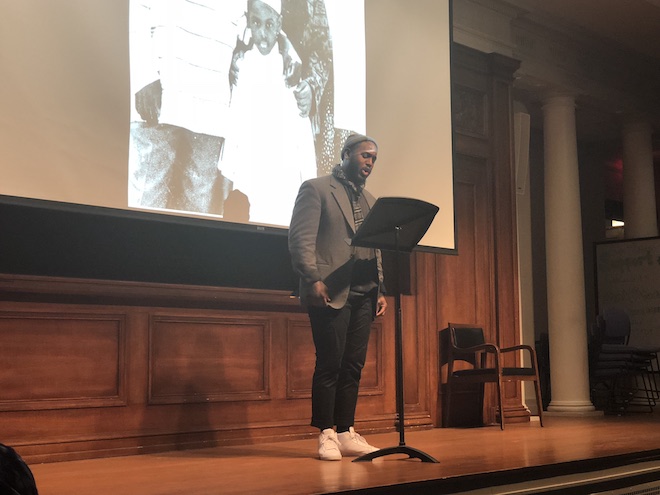

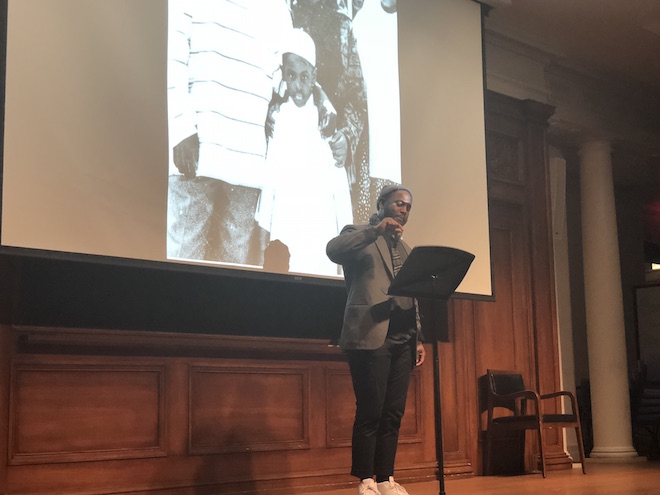

These are the instructions that Tariq Touré, a poet whose debut poetry collection is ranked in the top 500 in African American Poetry and Literature on Amazon and won Best Poetry Book of Baltimore in 2016, told the audience prior to his performance.

Touré and Khāled Siddīq, a Youtuber, singer-songwriter and writer, performed to members of the Northwestern community and others in Harris Hall on Feb. 20 for Poetry with a Purpose. The performance, hosted by the Muslim-cultural Students Association and For Member Members Only, was the first speaker event during the annual Discover Islam Week: Flipping the Script.

Following a recitation and translation of parts of the Qur’an, Touré explained the role of poetry and its ability to give depth to experience.

“It’s really important that we share poetry, that we share art in general, together because raw facts sometimes don’t tell the emotional time of people,” Touré said. “If I were just to say that 30 people died. 30 people died. What were their lives like? What were their stories?”

Touré reflected on the tension in Baltimore in his poem “April 27,” which he wrote after looking at a mural containing Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old man who died in police custody in 2015.

“I was told that you were somebody among the other somebodies that the system failed purposefully: another notch under a cruel society’s waist belt, a testimony to why we deserve these very conditions," Touré said. "I was told that your name was a climax in an American horror film entitled 'The Black body,' that your skin was made disposable.”

But Touré did not merely speak of tragedy and loss; he also spoke of revolution and hope.

“I looked Freddie in the eye today and saw one man who birthed 1,000 freedom fighters," Touré said. "I saw a man whose eclipse set fire to an army so convicted about being unshackled that they would rather taste tear gas than live another hour under oppression.”

Though Touré initially focused his poetry on Baltimore, he quickly established the parallels between Baltimore and Chicago.

“Chicago, like Baltimore, was one of the first pioneers of redlining. Baltimore instituted the first fresh off the press redlining laws, to corral Black folks into one big, huge district. Chicago, I believe, pioneered vertical segregation. I’m not sure how many of the buildings are up today, but they stack folks on top of each other like lab rats, and then say, ‘Survive.’”

After a poem about redlining that was inspired by Lawrence Brown’s “Two Baltimores: The White L vs. the Black Butterfly,” Touré also took time to criticize what he deemed liberals' “obsession with the trauma narrative.”

“Tell me how hard you had it growing up. Since we’re talking about Islam, a lot of people from where I’m from that had Muslim fathers and Muslim mothers had an alright upbringing, they had an OK upbringing,” Touré said.

Touré also highlighted the importance of recognizing how nuanced the Muslim identity can be as he described a recent interaction, in which someone asked him whether he was born or converted to Islam.

Touré equated how he is always asked whether or not he converted to Islam as a Muslim microagression, saying, “Imagine being around new people and having to answer that all of the time. Like, ‘Yeah, I’m Muslim, man. My folks are Muslim, Alhamdulillah. Yeah, I didn’t convert, man.’ By the seventeenth time, you have a chip on your shoulder like, what are you asking me that for?”

Siddīq also discussed the authenticity of identity as he introduced his song “My Grandfather was a Muslim,” saying that he hopes that his comfort in his identity can help others that struggle with finding strength in their own identity.

“I’m a Muslim, and I’m authentic, you know," Siddīq said. "I’m the real deal in hopes that I inspire people that are going through a crisis."

McSa president Sarah Khan also emphasized the importance of sharing the “nuanced identity” of the intersection of being Black and Muslim that “most of mainstream America does not know.”

“We want the Northwestern community to be exposed to other different narratives, more than that… the oppression of Black people and Black bodies in America, having everyone focus on that and how McSA gives speakers and poets like these a platform, to share even more knowledge and to share the emotions and humanization of these bodies, instead of just the numbers of what’s going on in America,” Khan said.