It was the first day of class in Stellenbosch, South Africa and I was exhausted after a week of orientation. As we settled into our seats, the professor launched straight into a calculated breakdown of American capitalism. Jokingly, or maybe not so jokingly, the professor suggested that the whole world should have a chance to vote in the upcoming U.S. election. After all, “It affects the international community so deeply, and those Americans haven’t been doing such a good job with it so far (no offense).” The other international students duly nodded in agreement.

Later, a month into my exchange, I was ignoring what had already become the ordinary: a guy, about my age, going on and on about the “good ol’ days”–thirty years ago, when South Africa had been at its economic height and moral depression. At the mention of Trump, I barely flinched. This was something else I had become accustomed to. Most times they didn’t even have to ask where I was from; the accent gave it all away. When they did ask, and I would answer, the smile would quickly turn into a jeer. “Well, who are you voting for?”

“Not Trump,” I would say, with an uneasy smile. Usually the teasing ended there, but often times it did not. I could only listen in horror as he continued on.

“Honestly, I hope Trump wins. As soon as he gets elected he would run the U.S. economy into the ground and reset the whole world economy. Then maybe South Africa could have another chance.”

I am not ashamed to say that I have probably spent more cellular data downloading politics podcasts than calling my family. My downstairs neighbors know I’m about to go on an elections-fueled rant when, halfway through preparing dinner, I’ll start pacing and speaking a lot with my hands. I have been in South Africa for four months now–approximately 80 TheSkimms and 160 New York Times Morning and Evening Briefings later.

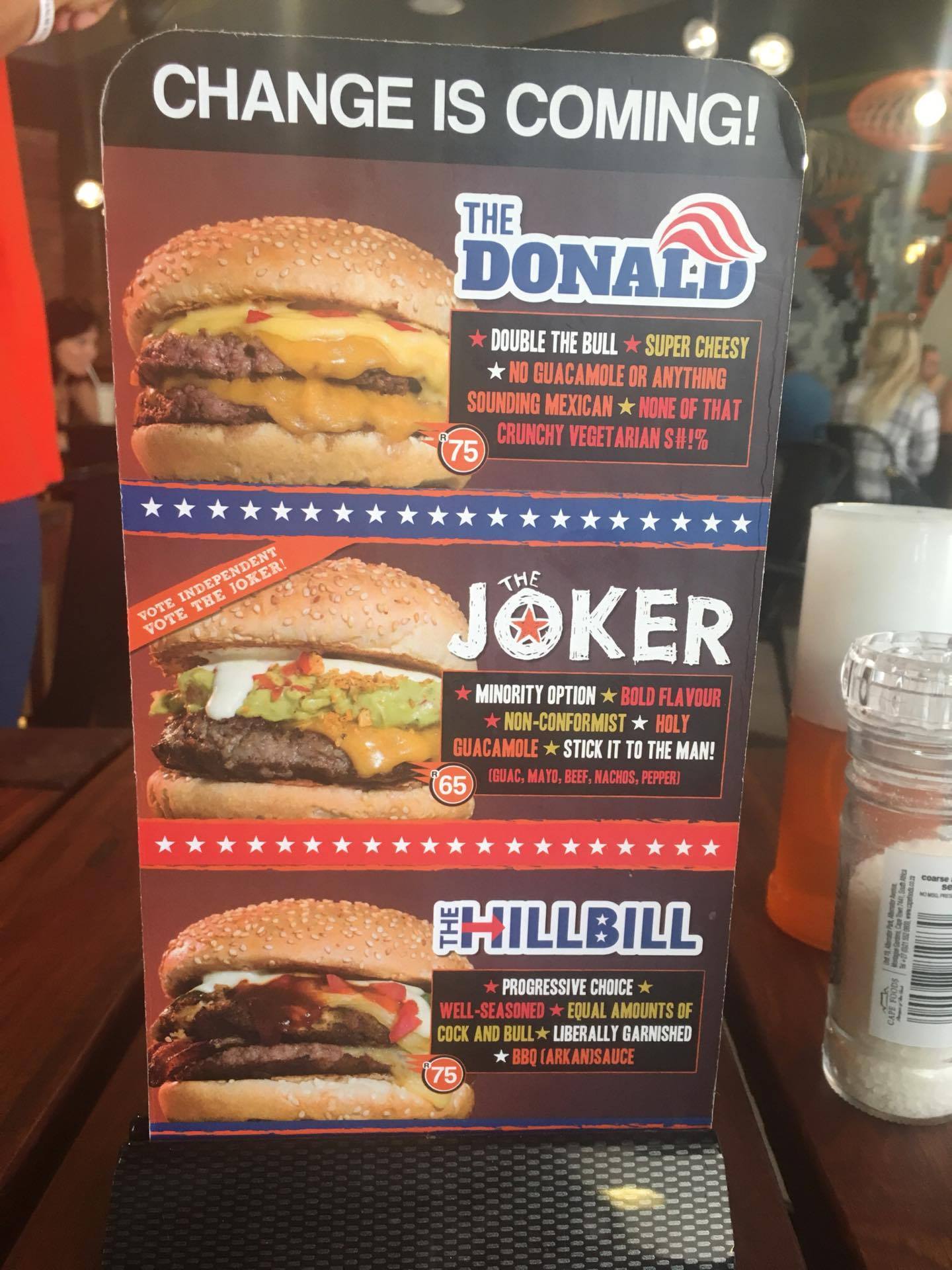

In these four months, I have heard my South African history professor compare Donald Trump to D.F. Malan–one of the primary instigators of apartheid in South Africa. I have seen bright red “Make America Great Again” hats peaking out over study cubicles in the library. I have gone for a burger after class only to be confronted by menu dish “The Donald” (“Double the Bull, Super Cheesy, No Guacamole or Anything Sounding Mexican, and None of that Crunchy Vegetarian S#!%”). Needless to say, the U.S. election permeates every corner of life.

But it’s not all about The Donald. The menu also boasts “The Hillbill.”

On a night walk through Camps Bay, I was confronted by an older couple’s discussion of the wire Hillary had supposedly been wearing during the first presidential debate. My friend from Australia calls her crooked. Once, on a late-afternoon train from Stellenbosch to Cape Town, a man instructed me to “smile like Bill Clinton’s wife.” Then he had asked me if I would accompany him to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But, to a certain extent, I am not surprised. South Africa is an endlessly complicated country. Socioeconomic disparities are rampant, and the government’s promises for reparations have not been met in full.

The part of South Africa where I am currently studying is located in the Western Cape. Stellenbosch is 21.5 square kilometers with a population of 155,733 (as of 2011). Kayamandi, a township only a few minutes outside of Stellenbosch, is almost 14 times smaller with a population of 24,645. That’s 7,243 people to a square kilometer versus 16,000 people to a square kilometer. And that is only where the inequalities begin.

Education has not been decolonized nor has it been made easily accessible, inciting the #FeesMustFall student protests that have all but shut down the majority of South African universities over the past few months. As a student, I have been confronted with fire extinguishers, locked libraries and cancelled classes; the protestors, on the other hand, have been met with dogs, stun grenades and rubber bullets, as well as arrests and expulsions. The heavily-armed private security here–referred to as the “men in black”–have even begun to wear numbers on their uniforms to make it easier for students to complain if, and when, things get “messy.”

Society has seemed to retreat into itself and emerging images of protests across South Africa strike an eerie resemblance to anti-apartheid struggles of the past. When I explained this to a family friend in Cape Town, he responded with a comically blank stare.

“But what about the police brutality in America?” he would ask. The implicit message was all too clear: OK, but how are you any better?

But, again, I expected this.

What I did not expect was that, behind the jeers and elbow jabs, there existed an almost palpable, nervous fear.

To most of the world, America is a joke, and in many ways I struggle to defend it. However, the only way to change the state of our democracy is to participate in it. After that you are free to gripe, free to groan at me when I start to talk politics, to roll your eyes so deep into your skull it hurts. But, until then, get informed and get out the vote because, believe me, the world is watching.

Don’t we want to prove them wrong?