Students from 6,500 different high schools across the country applied to Northwestern last year. They wrote essays, listed basic personal facts and submitted myriad forms, hoping to receive the “big envelope” of acceptance in return. Many of these students completed the Free Application for Federal Student Aid and the College Scholarship Service Profile, requesting monetary assistance to cover the costs of university tuition. Northwestern has one of the largest financial aid programs in the country for a private university, so applicants sold on the “Northwestern experience” ideally receive the financial assistance necessary to afford enrollment.

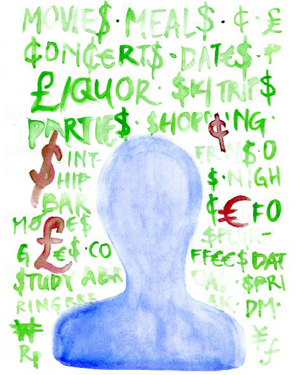

The problem is that this optimal experience costs more than just tuition. While flyers, tour guides and university websites tout participating in Dance Marathon or attending a boat formal as essential activities, they neglect to mention the monetary requirements. Most Northwestern students have the financial cushion necessary to partake, but a small subsection of campus often does not: low-income students.

Roughly 15 percent of Northwestern’s undergraduate population receives a Pell Grant, which is awarded to students from families with income levels around $40,000 or less. There is no prototype of the low-income Wildcat; he or she can be found in every school, club or residence hall and can represent any race, ethnicity or religion. What binds these students together is the fact that the experience they were promised upon acceptance can unravel once they arrive on campus.

Tessa D'Agosta: Isolated by Income Level

One night well into her sophomore year, Tessa D’Agosta was playing pool with another resident in the basement of Public Affairs Residential College. During the game, she made an offhand remark about how her Virgin Mobile cell phone wasn’t working properly.

“He just looked at me and said, ‘Virgin Mobile? Why do you have that? Why don’t you just ask your mom to buy you a new phone?’” says D’Agosta, now a junior in Medill. “I was like, ‘I don’t even want to have this conversation with you right now.’”

D’Agosta is a recipient of The Patrick G. and Shirley W. Ryan Family Scholarship. Founded in 2006, the scholarship program replaces the loan in top low-income students’ aid packages with a grant, allowing recipients to attend Northwestern debt-free. In total, D’Agosta receives about $60,000 in financial aid each year.

Last spring, D’Agosta attended a focus group meeting specifically for Ryan Scholars. The meeting was organized by the administration with the goal of learning more about the low-income student experience. Participants’ answers were recorded and meant to be kept private, although a few select questions were asked to the whole group. One of the group questions asked where the students felt they fit in on campus.

“Someone answered first and was like, ‘I don’t really have anyone on this campus.’ And then slowly, four, five, six more people said the same thing,” D’Agosta says. “That’s exactly how I feel. I don’t feel like I fit in anywhere. And it was really weird to me—and kind of awesome, in a bad way—that OK, maybe I’ve found the reason.”

D’Agosta hasn’t spent a lot of time with her fellow Ryan Scholars. Once, they went to a Cubs game together; the University bought their tickets and provided them with $20 meal vouchers. Yet at that focus group last spring, she found herself relating to the Ryan Scholars in a way that has been difficult to do with other Northwestern students.

“The socioeconomic background is such a key part of who I am, the relationships that I form and the way I think about everything,” D’Agosta says. “It’s hard to make new relationships with people when they don’t understand where I’m coming from.”

Greg Shanahan: Culture-Shocked

Weinberg junior Greg Shanahan attended what he calls a “blue-collar high school” and did not expect to be accepted to Northwestern—to the point where he didn’t even apply for financial aid from the University. After receiving his acceptance, Shanahan filed late financial aid paperwork and was eventually awarded free tuition. He decided to attend, passing up an offer from the University of Nebraska that included free tuition, money for books and a housing stipend. When he arrived at Northwestern, however, Shanahan experienced a major culture shock. “I immediately noticed that there’s a lot of money thrown around,” he says. “There’s a general attitude of elitism.”

Early in his freshman year, Shanahan and several of his suitemates were sharing their previous summer’s job experiences. Shanahan mentioned he had lifeguarded at home in Omaha, Neb., while a friend said he had done park maintenance in his own hometown. One of their other suitemates then asked why they would ever work for their own money when their parents could provide funds instead.

“He follows that up by going, ‘Why would you like mowing grass? That’s what wetbacks are for,’” Shanahan recalls. “The worst part was I didn’t even say anything to him. I didn’t argue with him or try to express my opinion or reprimand him because I felt like I was in the minority.”

Shanahan also says that classism drove him to quit the men’s club soccer team at the end of his first season. During the spring of his freshman year, the team stopped at a Culver’s restaurant on the way to games in St. Louis, Mo. While at the restaurant, Shanahan recalls, one team member said he would “feel like such a failure” if he ever brought his family to a restaurant like Culver’s.

“They don’t even consciously realize the effect that their words are having on other people who may not have had the same experiences in life,” Shanahan says. “You can’t really hold that against them, but at the same time it makes you cock your head and wonder.”

Shanahan felt so uncomfortable at Northwestern by the end of his freshman year that he filed to transfer to Nebraska. His two best friends had decided to transfer, and he hadn’t fit well with the campus culture. These setbacks, plus two bad roommate experiences in two different residence halls, had Shanahan ready to leave Northwestern for good. Ultimately he decided to stay, saying that he didn’t want to feel like a “quitter.”

Shanahan knew the opportunities Northwestern offered were superior. He studied abroad in Turkey this past summer, is currently studying in Scotland and will be in Washington, D.C. next quarter as part of the Medill on the Hill program for non-majors. But while he’s met some of his best friends on this campus, Shanahan doesn’t quite bleed purple.

“While other people are already dreading the end of college and worrying about being out in the real world, I’m kind of loathing having to be at Northwestern before graduation,” he says.

Shanahan only has four quarters left on Northwestern’s campus. In that time he wants the University to start creating a space for a larger contingent of low-income students—or, at the very least, a platform for these students to voice their experiences. Each time he found himself frustrated with the state of affairs on campus, he would complain to his friends before miserably deciding to “suck it up and deal with it.” At the end of this past summer, he reached out to Tessa D’Agosta, and the two of them made plans to found a publication, which they plan to call The N’Dependent—a name that pays homage to their shared Nebraskan roots. The idea is to contact individuals who have experienced struggles with classism, racism and other issues on campus and ask them to share their personal stories in hopes of generating a discussion.

“There have been a few times where I’ve tried to talk about this, and I’ve had people tell me to ‘shut up and have some school spirit,’” Shanahan says. “They just didn’t want to listen to why somebody might not feel Northwestern is as awesome as they think it is.”

Amanda Walsh: Pushed to the Limit

When Amanda Walsh first arrived at Northwestern a year ago, she was embarrassed to tell people she was a low-income student. Instead, she tried hard to keep her socioeconomic background a secret, struggling to keep pace financially as her roommate and friends were going out downtown and indulging in expensive activities.

“I dug myself into a hole because I felt like I had to in order to make friends,” says Walsh, a Communication sophomore. “The first quarter, I ended up having $0.08 left in my bank account because I was trying so hard to keep up with everyone.”

Walsh attends Northwestern as a Quest Scholar and with the help of a Good Neighbor, Great University scholarship. When she did try to avoid expensive activities, she still felt too uncomfortable to admit her income status. Instead, she devised other reasons to explain her absence to her friends—which resulted in precisely the social backlash she had tried so hard to elude.

Last year, Walsh’s friends signed up for Northwestern Ski Trip as soon as tickets became available. They proceeded to badger her about why she hadn’t done the same. Unwilling to tell her friends that she couldn’t afford the trip, she cycled through several excuses. First, she didn’t like skiing, then she was no friend of the cold. When her friends refuted all of her excuses—Ski Trip is about more than skiing, they said, and as a Chicago native, Walsh cannot cite cold weather as an excuse—the conversations turned more personal.

“It got to the point where they were like, ‘Oh, you’re being a baby, just sign up. Why don’t you want to be with us?’” she says. “They were almost attacking me because they felt I was attacking them [by not going].”

Around that same time, one of Walsh’s other friends was planning her half-birthday celebration downtown. The celebration’s agenda included a dinner in the city followed by a night out, complete with VIP tables and bottle service. When Walsh hesitated about going due to the expensive nature of the activities, the friend started arguing with her. Eventually, Walsh ended up attending the celebration to avoid upsetting her friend, receiving the necessary funds as an early birthday present from her parents.

These incidents were rooted in Walsh’s discomfort with her low-income status. But as she became more involved with Northwestern’s chapter of Quest, a low-income advocacy group that comprises roughly 300 students, she realized that she was not alone in her monetary struggles. After she joined Quest’s executive board as treasurer last February, she had a conversation with a fellow exec member that inspired her to embrace her low-income status.

“I broke down and said, ‘I feel so uncomfortable being a low-income student at this institution and telling people that I am a low-income student because I feel like I will never have friends.’ She told me that the most important thing is to just be yourself and to be comfortable with who you are,” Walsh says. “From that point, it was like a complete 180 for me.”

Daniel Flores: Misled by False Advertising

Communication senior Daniel Flores felt out of place the first day he moved into Northwestern three years ago. As his peers hauled huge television screens into their dorm rooms, he brought only two suitcases. He says the feelings of unwelcome were intensified because he is a Hispanic male—not exactly the type of person most students visualize as the prototypical Northwestern student, Flores believes. He was routinely asked for his WildCARD by police to prove he belonged on campus and was even questioned by the community service officers who monitor the residence halls after dark. Once, Flores recalls, another student asked him for his food, implying that the student thought Flores was his delivery man. Flores was even wearing a Northwestern sweatshirt at the time.

“My freshman year was horrible,” says Flores, who is co-president of the Northwestern chapter of Quest. He says that despite promises of “One Northwestern,” his first year in Evanston in particular didn’t live up to its billing.

Flores supported himself by working multiple jobs at once during his freshman year, which prevented him from participating in potential memory-making activities and caused him to question his own identity as a student. Coupled with the fact that others sometimes didn’t see him as a Wildcat either, Flores began to wonder whether he should have just stayed home and worked. “I wouldn’t have had to deal with all of this other stuff that makes me feel less human than everyone else,” he says.

A greater presence of low-income students at Northwestern might help students like Flores. Increased admission of low-income students would be a possible solution—but it’s not that simple. Northwestern claims need-blind status when it comes to admissions, which means the school does not consider an applicant’s financial situation during the decision-making process. That works both ways: Not only is the University prohibited from rejecting a student because of his or her level of need, but it also cannot see an applicant’s financial statistics at all. As a result, making a concerted effort to admit more students from lower socioeconomic statuses is virtually impossible.

Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Christopher Watson says that demographics do factor into admissions decisions, albeit indirectly: Certain inferences can be made based on an applicant’s personal information. The Office of Undergraduate Admissions buys data on high schools across the country every few years, so admissions officials may be able to identify students from modest backgrounds based on their high schools or hometowns. “We work really hard to get to schools where we know they’ve got a number of high-achieving, lower-socioeconomic students, but sometimes that’s difficult,” Watson says.

At the end of the day, the primary goal of Northwestern’s admissions office is to find the next batch of freshmen to march through the Arch, not to appeal specifically to students from lower socioeconomic statuses. There’s a difference between recruitment and outreach, Watson says. “Recruitment is recruiting a class of 2,025 every year for Northwestern. Outreach is just trying to get some high school students to think about college,” he says. “Our main role is obviously recruitment.”

But for someone like Flores, who says he is and will be the only person from his high school to attend Northwestern, standard recruitment may not be enough. “Northwestern is one of the worst places for a low-income student,” he says. “You are not set up for success.”

Kyle King: Inspired by the Future

Even low-income students who feel a sense of allegiance to Northwestern struggle at times. Communication junior Kyle King, who is in the process of transferring to Weinberg, appreciates the opportunities Northwestern has afforded him. But getting started at Northwestern proved difficult—even before he arrived on campus.

For King, acquiring the financial aid package he needed to attend Northwestern was complicated because his parents divorced when he was 14 years old. While his father’s income is higher than his mother’s, King was not going to be receiving funds from his father. Thus, he could only afford to attend a university that would waive his father’s wages when considering financial aid. One of King’s final choices, Williams College, was not willing to waive his father’s wages.

King had to submit court papers to Northwestern detailing the circumstances of his parents’ divorce, including notes from his mandated therapy sessions from the time of the divorce. These notes proved his lack of a relationship with his father. Once Northwestern agreed to consider only his mother’s income, King gave up on pursuing the wage waiver from Williams; the process was simply too exhausting to complete again.

But King says he is incredibly thankful to have had the opportunity to attend Northwestern. While he has had his fair share of alienating experiences—one of his friends shops at Burberry, for example, which makes him feel awkward—King says Northwestern has provided him opportunities he wouldn’t have had otherwise. He is currently abroad in Italy, a venture funded by his financial aid. Northwestern allotted him $4,500 per quarter; he says his living expenses amount to about $2,000 per quarter, with roughly $1,275 of that total comprising three months’ rent. As a result, King has had funds available for additional travel, which has allowed him to have a fulfilling study abroad experience.

King says that while many students complain about the state of affairs in Evanston, it’s up to them to spark discussion about these issues. “People give Northwestern so much shit and expect it to be this utopia, but I feel like we’re supposed to be the generation that changes it,” he says. “As much as I feel uncomfortable, I’m also going to be the one that’s going to call someone out if they make me feel uncomfortable.”