“Look into my eyes and you’ll see that fear ain’t only skin deep, at least not for me,” implored Max Alexander, protagonist of The Alexander Litany, at an open mic reading on an unnamed college campus in Southern California.

Kori Alston, 20-year-old playwright and Communication sophomore, first spoke these words at a 2014 slam poetry competition. To follow, he wrote them into his new play, creating Max Alexander, a young man who contemplates his racial and sexual identity, as a means to express his frustration. The final product was performed as a staged reading in Shanley Pavilion January 15-16, 2016.

“In every good slam poem there is universal truth, there is personal truth, and then there is a kind of truth for the audience,” Alston said.

Through his writing, Alston said he attempts to draw in audience members by tapping into his own experiences. His play comes at a complex time in American race relations. As the country contemplates claims of institutional racism and a growing understanding of its prevalence, Chicago continues to struggle against racist policies and claims of racial police brutality. After a series of high profile shootings of unarmed black men in recent months, thousands of Chicago activists took to the streets.

Alston said his writing is a way to engage with Chicago’s ever-present activism by bringing a conversation about race relations to Northwestern. He said he sees theater as the most productive way to explore humanity.

Litany is Alston’s first race-centered work on campus, but not the first time he has joined the conversation. He spoke at the Black House in November when students of color hosted a march in solidarity with University of Missouri and other schools where students were protesting institutional and systemic racism on college campuses.

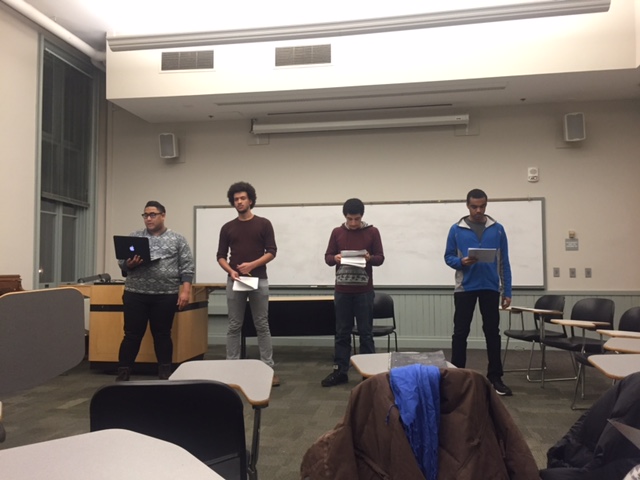

Alston’s play addresses the complexities of race, following four Black men spanning three generations. Each channels his anger or apathy via individual monologues throughout the show.

Alston consciously chose a white director, Mary Kate Goss, for the play, which debuted to a majority white audience. The last show, however, brought about 50 percent people of color, creating a different environment for the audience, according to Alston.

The play, which ran an hour-and-a-half, was performed by four Black students and three white students. Only one Black man auditioned for the show, so Alston and Goss reached out to people outside the undergraduate theater community to find more Black actors to fill the roles for the show. They even enlisted a Northwestern graduate student to fill the role of Clarence, Max’s grandfather.

Though initially hesitant about why Alston reached out to a white woman who had never struggled with Blackness, sexuality or mental health like the characters in the play, Goss said she soon realized how important it was for people who looked different than those on the stage to spur conversations by putting real life onstage.

“Max [the character] and Kori [the writer] stand for the same things, but Max channels his feelings through rage and fighting, while Kori creates art,” the director said.

Like Alston, Alexander grew up with a white mother and an absentee Black father. Both struggled with their relationship to a Black world. Both are college students far from home, angry with the racism they face every day. But the boys are different in how they confront their dissatisfaction.

“My relationship with Blackness was with my father. He was such a negative part of my life, and it was easy to associate Blackness with the bad parts of my father. I wanted to be white,” Alston said.

As someone with a white mother and Black father, Alston used to refuse to racially identify, partially because he began to dislike the Black parts of himself, he said. As he got older, Alston said he began to confront racism by a “Fuck you; I’m Black” attitude and growing his hair out to emphasize his Black identity.

He vacillates between wanting to disrupt spaces and make noise every time he hears a Black person was killed, to trying to find a safe space to challenge white audience members’ way of thinking.

Black discontent weaves its way through the lives of the Alexanders, through individual monologues and a discussion of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Alston’s work is based upon the complexities of black America, demonstrating that there is no universal Black reaction. Alston’s goal is to spark conversation, but does not intend to direct that conversation.

“If people aren’t ready to have these conversations without seeing a play about race first, then I’ll write them the play,” he said.

The Alexander Litany also examines masculinity. To Alston, this play is a messy representation of Blackness and manhood.

“To me, the things we need to talk about or the ones that are the most crucial are femininity and how easily we break down and quantify that, the environment and race,” he said.

Alston is Black, white and Native American. He is an animated speaker, rarely pausing to even sip his coffee. Just as The Alexander Litany explores different versions of Black racial identification, Alston’s works explore the different mediums through which his audiences can begin to understand the racially charged atmosphere for a Black man in America, especially as he surrounds himself with the complex, racially segregated city of Chicago.

“Being mixed race in America and dealing with the juxtaposition of being Black and white, which have been set up as antithetical …, race is something I think about a lot,” he said.

While growing up, Alston came to terms with his racial identification and starting exploring facets of not only his personality, but also of his mixed race. The Alexander Litany attempts the same task, with each character confronting his or her race differently. The Black narrative is not singular, and neither is Alston’s.