Unpacking on a foreign campus

College first-years who return home claiming that freshman year was all fun and games may just be blowing smoke. Like many others, Weinberg freshman Xavier Vilar-Brasser’s first year was stressful, but he found an escape in an old habit.

“In college I thought about quitting, but it’s just too much,” Vilar-Brasser said. “With all the stress of school, it’s a lot to take on, and it becomes a crutch. You’re always stressed, and then when you’re stressed, your go-to thing is to have a cigarette.”

Vilar-Brasser was one of 277 undergraduate international students new to Northwestern in 2016. This global group hails from many different countries, from the U.K. where Vilar-Brasser lived until the age of nine, to Peru where Elna Alvear Mayser comes from. Mayser is a communication freshman who finds smoking culture much more relaxed back home.

“I can smoke a cigarette in front of my mom, and smoke it with her,” she said. On move-in day, Mayser smoked a cigarette with her mom. Her roommate, in turn, was shocked. “[My roommate] was like, ‘Are you crazy? My mom would kill me.’ That’s just like such a difference, you know?”

Although Mayser experienced this stark contrast in cigarette connotation, current Peruvian policy mandates smoke-free universities, whereas the United States does not. While more public spaces are legally free of smoke in Peru than in the U.S., the difference seems to lie more in public perception than public policy. Vilar-Brasser saw similar attitude differences when he traveled to South Korea.

“In Korea, everybody smoked,” he said. “In America, people are so against smoking. In Europe, you get a pack of cigarettes and you’ve got the big label on it that says, ‘This will kill you,’ but then nobody really cares as much. There isn’t as much awareness, maybe, or people are living their life too freely to care.”

Control and culture: second-hand perception?

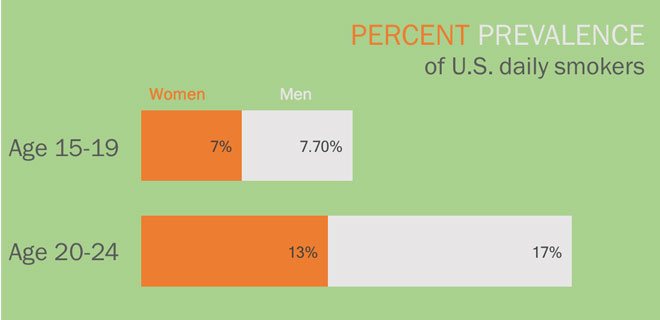

In 2014, 13 percent of college students in the U.S. reported smoking one or more cigarette in the last month, as found by the University of Michigan’s Monitor the Future study. Five percent, meanwhile, expressed daily smoking. Yet despite the fact that some American students smoke, others link the act with its inevitable consequences.

Mayser finds that in the U.S., people tend to share fixed views on smoking because of its association with cancer. But in Latin American culture, she said, in her view, “it’s just like they don’t think of it. They just think like, ‘Something is gonna kill me anyways, so might as well smoke. It can kill me, but something else will kill me eventually.’”

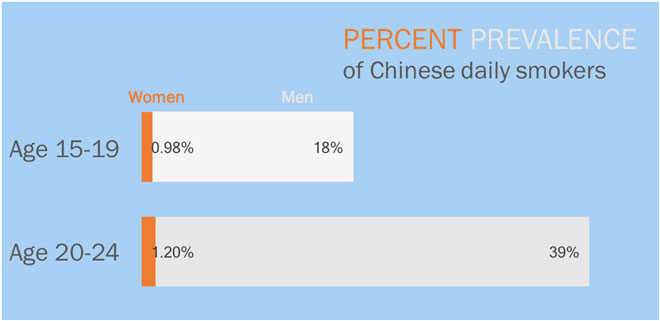

The lack of tobacco control policies in certain countries also contributes to a culture more supportive of smoking, according to International Tobacco Control Project founder and Unviersity of Waterloo professor Geoffrey Fong.

“Laws are also an indication of what society values. In countries like China where tobacco control laws are very weak, of course the culture is going to be more supportive of smoking,” Fon said.

Unlike China, guidelines aimed to protect citizens from tobacco smoke exist everywhere across the European Union (EU), although their nuances are varied and distinct. The link Fong proposes, however, does not appear to translate into direct personal opinion, at least as Vilar-Brasser sees it.

“Smoking here is ‘trashy’. It’s like you see a kid smoking and you’re like, ‘Oh that’s ‘dirty,’’ or ‘they’re sketchy.’ There are all these assumptions that come with someone smoking a cigarette, where in Europe it’s just like, ‘Oh, they’re smoking a cigarette,’” he said. “You can be like, ‘Oh, that’s gross,’ but you don’t make assumptions about a person based on it.”

Lighting up student views

Vilar-Brasser, Mayser, and Medill freshman Oreste Visentini come from far and wide: the first two grew up in London and Peru, respectively. Visentini, on the other hand, was born in Italy and attended high school in Mexico. Yet they all spoke to the same underlying, unspoken cynical reaction from other students when spotted smoking.

“I feel like their first reaction is kind of negative, just by looking at their facial features and how they react. But they’re not going to do anything,” Visentini said. “I think their response is a little negative, but at the same time, they respect my decision. They don’t really make a fuss about it or try to get me to stop.”

The average Northwestern student may not interrupt their daily grind to voice opinions on cigarettes, but ASG recently shared its views on the issue. Two years ago, the organization rejected a resolution for support from the student body of a tobacco-free campus co-proposed by then-freshman Ross Krasner.

“They were worried that this was overly-paternalistic,” Krasner said. “I remember someone made the exact argument: if we banned cigarettes, what’s next? Are we gonna ban cookies ‘cause cookies are also bad for you? We also had a number of concerns about how staff would be affected, like Sodexo employees.”

Sodexo employees are allotted ten minute breaks that may not allow them enough time to leave the campus to smoke. Following the resolution, ASG also raised similar concerns regarding another group on campus: international students.

“I have a friend who’s an international student, and he smokes like two packs a day,” Krasner said. “The last thing I want to do is make him walk a mile every time he wants to smoke."

A little [pack] of home

Data comparing smoking habits of international versus American students are few and far between; comparison statistics don’t really exist. Still, Fong argues that how a given culture perceives smoking translates into how its people continue to use the product, even outside their national borders.

“There will be differences in smoking rates among students from other countries, likely at about the same rate as their home country,” he said. “In most countries, smoking starts in the teenage years. These smokers didn’t start smoking at Northwestern; they started smoking before they got here.”

In 2015, the European Youth Portal found that a quarter of young adults (aged 15-24) in the EU smoke. Nicotine is a notoriously hard habit to kick, so those international students who start may not stop after coming to Northwestern. In other corners of the world, social convention contributes to cigarettes as a way of life.

“It’s a moment where you’re just devoted to [smoking] and you can have a conversation with someone if you’re smoking a cigarette outside, just like connection,” Mayser said. “In Lima, it’s like a whole thing to go and meet the person somewhere, in a park or in front of the ocean. It’s just so different.”

Lima and Evanston are worlds apart, but continental geography is not their only divide. NU’s campus environment is also impacted by its regional location: the Center for Disease Control discovered that 25.4 percent of adults in the Midwest smoked cigarettes in 2014, the highest of any region. Yet Visentini gathers from experience that a campus atmosphere offers its own implications.

“I think the campus does make a difference, because it’s a group of people that are more similar to you,” he said. “If someone doesn’t want their friends to know they smoke or people they know, on campus they might smoke less just because they have that chance of encountering. But I think being in the city, someone would probably smoke a bit more.”

The City of Evanston’s own Public Health Manager, Ikenga Ogbo, said Evanston would support a movement for a smoke-free or tobacco-free campus at Northwestern. This proposal is currently off the table, but Krasner sees its potential return to the agenda.

“When it failed, that was the last that it has come up,” Krasner said. “There’s been no efforts to revitalize that campaign as of this time. It could potentially come up again in the future, because I’m sure it will.”