“Where are you really from?"

The seemingly innocuous questions is a common one, often directed at Asian Americans. But what might seem like a matter-of-fact inquiry actually implies something more derogatory. “It’s fundamental racism,” said Professor of Asian American Studies Ji-Yeon Yuh, “the assumption that is if you are Asian, you de facto don’t belong.”

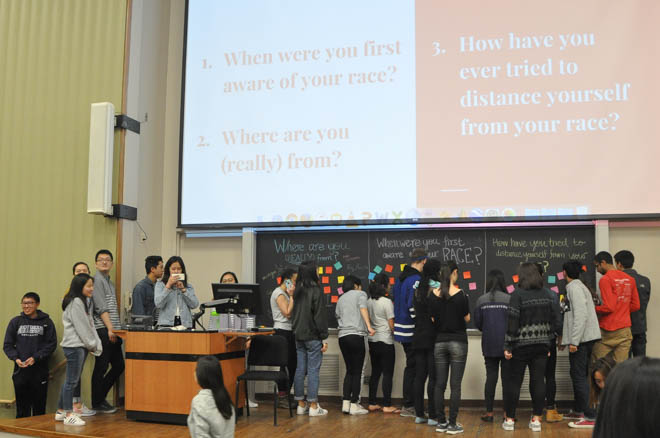

The question was the subject and the title of a panel discussion on Tuesday night. Students filled almost every seat of Fisk 217 to hear three Northwestern Asian American Studies professors discuss Asian American’s relationship to Black Lives Matter, the history of Asian American identity and their future within a globalized capitalist world.

Associate professor of anthropology and Asian American Studies Shalini Shankar explained how the question exists alongside other subtly racist slights that are today labeled as "micro-aggressions," but that have long existed. She recalled seeing discrimination against bilingual speakers and people mocking Asian American accents as a PhD student at New York University.

"[These are] small ways that racial formation occur in every day live centered around certain understanding of difference," Shankar said, comparing the anti-Asian sentiment to anti-Arabism that has manifested in Arabic speakers being forced off aicrafts out of fear that they are terrorists.

Yuh later broke the question down into blunter terms. She described being told that she did not "look like a Chicagoan” after telling someone that she is from Chicago. What the question implies is, “I belong here, this is my house, this is my country, you don’t belong here, so you better tell me where you’re from,” Yuh said.

Yuh traced the origins of anti-Asian sentiment to the 1790 Naturalization Act that declared that only free whites could become naturalized citizens of the United States. For that reason, Yuh said, Asian Americans have been involved in fights for citizenship, as well as for economic rights, since they first came to the country.

Yet in recent years, Asian Americans – a term that Yuh said originated around the same 60s era racial liberalism birthed “African American” – have been criticized for failing to take part in activist movements surrounding other people of color. As racial justice protests swept the nation in the fall, Princeton student Kevin Cheng penned an essay in The Atlantic criticizing the lack of Asian American involvement. In recent months, the trial of New York City police officer Asian American Peter Lieng put the Black Lives Matter movement at odds with some Asian Americans, who felt Lieng was being punished where many white cops escaped prosecution.

Professor Nitasha Tamar Sharma recalled the 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, where Korean salons and shops were attacked. The shop-owners responded by saying they had just been working and had done nothing to African Americans. But Sharma argued that just working wasn’t an excuse not to be involved in struggles for civil rights, or to be uninformed about racial politics.

Sharma said that Americans and Europeans had exported ideas and stereotypes of anti-Blackness to the world, so that when Asians emigrated to the US, many tried to disassociate themselves from Blacks to better assimilate into society.

“Asian Americans have been complicit in the advantage that whiteness brings,” Sharma said. "You don’t have to be white to be part of white supremacy.”

Still, Yuh argued that being knowledgeable and knowing how to talk about race is a privilege, and that those in poverty or who are struggling to stay middle class may not have the luxury of time to march in the streets.

Ultimately, the panelists agreed that for Asians to not be complicit they should avoid and pressure the capitalist structures that have contributed to racism and oppression. Professor Shakar suggested looking at which institutions perpetuate these hierarchies. She pointed directly at Northwestern.

“Look at Northwestern – the higher up in the administration you go, the whiter and maler it gets,” Shankar said.