“We would like to take a second to acknowledge the ground that Northwestern University stands on – this land was, and is, home to Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Odawa tribes, as well as countless other tribes and nations that came through here,” Asha Sawhney, a co-president of Northwestern’s Native American Indigenous Student Alliance (NAISA) said.

In the Scott Hall Guild Lounge on Saturday afternoon, a reception hosted by NAISA honored the Cheyenne and Arapaho people who lost their lives on Nov. 29, 1864, in the Sand Creek Massacre.

During the massacre, around 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho people in a village along Sand Creek, in the Colorado Territory, were killed by U.S. soldiers. The majority of them were women, children and elders.

John Evans, one of the founders of Northwestern, was the territorial governor of Colorado and ex-officio superintendent of Indian affairs at the time of the massacre.

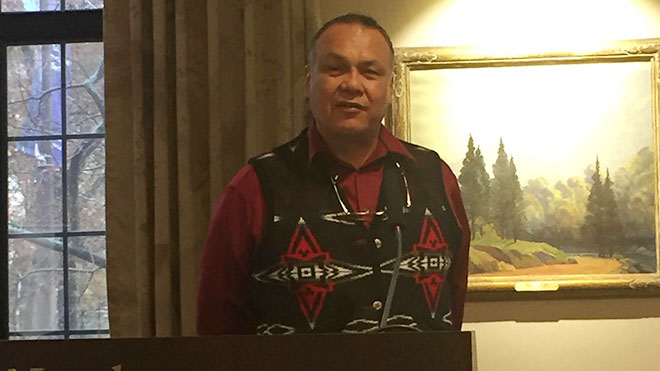

The reception hosted Otto Braided Hair, a Sand Creek Massacre descendant who is Northern Cheyenne and a lead organizer for the annual Sand Creek Massacre Healing Walk and Run, as the keynote speaker.

photo by Karli Goldenberg / North by Northwestern

Following a prayer, Jabbar R. Bennett, associate provost and chief diversity officer at Northwestern, emphasized the importance of recognition.

“The work that we are attempting to do, to acknowledge those who came before all of us who sit here, but also all of us who acknowledge Northwestern’s role in not only the massacre, implicitly and otherwise, but also the role that we have played as an institution that might contribute to things that have been unfair and unjust as well,” Bennett said.

Lesley-Ann Brown-Henderson, executive director of Campus Inclusion and Community and interim director of Multicultural Student Affairs, explained the importance of a petition that former NAISA president Heather Menefee (WCAS '15) started in fall 2012.

“That petition was for the university to do something and acknowledge the participation of John Evans in the Sand Creek Massacre,” Brown-Henderson said. “Here we are five years later. Think about where our campus has come because of the [activist efforts] of those students.”

Sawhney talked about the Norris Social Justice Committee’s efforts to rename the Evans Room (102) to the “Potawatomi Room.”

“We continue to struggle to try to get some of that renaming done,” Sawhney said. “Starting the 29th of November, we will be projecting some of the relevant words surrounding the Sand Creek Massacre in the Evans Room in Norris to get people thinking, ‘Who is this room named after?’ and ‘Why are we commemorating him over those who suffered during Sand Creek and their descendants?’”

John Low, an associate professor at Ohio State University who is a member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, spoke to his roots and the importance of recognizing land as Native.

“There is no doubt that we were the ones at the battle of Fort Dearborn, we were the ones at the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, we were the ones that Simon Pokagon came and spoke before 70,000 people at the Columbian Exposition, we were the ones who sued for the Chicago Lakefront and took the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court in 1917,” Low said. “We know that we walk on the bones of our ancestors and that the land cannot be sold, cannot be given. It also cannot be lost. It's still our land, and yours.”

Gail Ridgely, who is a Northern Arapaho Sand Creek Massacre descendant, spoke about the importance of oral history.

“What history forgets is that our Indian people have oral history," Ridgely said. "Western historians didn’t accept oral histories because to them it wasn’t relevant to today’s society. Our oral histories are very strong."

Ridgely also emphasized the injustice of the congressional hearings following the Sand Creek Massacre.

“It was outright murder – three congressional hearings, no one was found guilty,” Ridgely said. “Arapaho and Cheyenne people are warriors. They’ll never quit. Truth has to come out.”

George Levi, a Sand Creek Massacre descendant who is Southern Cheyenne, connected Sand Creek to the genocide of Native peoples globally.

“History is always told by the conquerors, it’s never told by the [conquered],” Levi said. “The story that’s being told about Sand Creek didn’t just happen to the Cheyenne and Arapaho people, it’s happening all over the United States. It’s happening right now in South America to our people in Brazil. It happened in Canada, it happened in Central America. Genocide – that’s the only way to say it.”