I interviewed four Northwestern students from across the political spectrum in an attempt to understand ideological diversity on campus and what is lost in our struggle to communicate about political differences.

After the initial shock of the 2016 election, Julia Cohen couldn’t bring herself to continue attending College Republicans meetings.

“I was struggling a lot,” said Cohen, a senior social policy major in SESP who until November had served as the organization’s vice president. “I didn’t know if I even wanted to identify as a Republican anymore.”

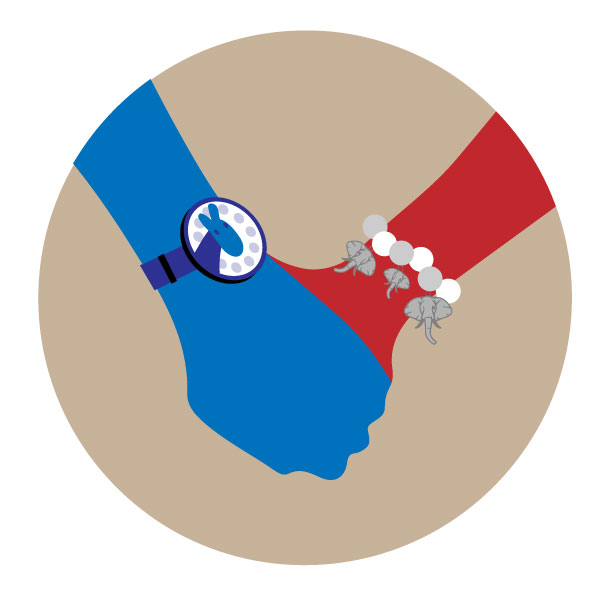

For many students on Northwestern’s campus, the cataclysmic presidential election has led to a heightened awareness of political identities and a struggle to navigate a culture in which political and personal identity are almost inextricably intertwined. For those whose political beliefs diverge from the student body norms, the question of politics and identity is even more urgent due to the social fallout that can result from conflicting views. However, political identities aren't as clear-cut, red and blue, as some people might think. Many political identities are the heavily influenced by family environments, communities and personal life philosophies.

The decision about whether or not to endorse a candidate in the election seemed emblematic of the identity crisis faced by many conservatives after Donald Trump secured the Republican Party’s nomination. Republican student groups at other universities like Harvard had publicly disavowed the candidate in prior months. While NUCR eventually chose not to endorse him, Cohen believes most of the group’s membership voted for Trump.

“They didn’t support him, they didn’t like him, but they did vote for him,” Cohen said. “At least that was my understanding.”

Cohen grew up in a liberal family in New York City and maintained similar liberal beliefs to her family until coming to college. Contrary to the common narrative that young people adopt more left-wing views in college, Cohen found that her studies guided her in a more conservative direction.

“I took econ classes, ” Cohen quipped when asked what triggered her change of heart.

While she comfortably identified as a Republican for several years, the rise of Donald Trump made her question that alignment.

“There’s a quote from an old Barry Goldwater commercial: ‘either he’s a Republican, or I am – but we’re not the same thing,’” Cohen said. “That’s kind of how I see it.”

Cohen now identifies as a libertarian, and has been involved with the Northwestern chapter of Young Americans for Liberty, a libertarian-values organization born from Ron Paul’s 2008 presidential campaign. She said she believes in the importance of limited government, protection of personal freedom and a more conservative economic agenda, finding herself generally aligned with the left on issues such as gay marriage and marijuana legalization, and with the right on issues such as gun ownership and fiscal responsibility. Faced with the prospect of a Trump presidency, she voted for Hillary Clinton without hesitation, who she otherwise would not have supported.

And while the general consensus on campus seems to have leaned overwhelmingly in Clinton’s direction, Cohen said there are a number of students who voted for Trump but are reluctant to admit this outside of like-minded circles due to the social stigma of being an open Trump supporter. Add to the mix those who voted for third party candidates or who didn’t vote at all, and Northwestern’s election tally may in fact tell a story less congruent with the homogenous progressive liberalism with which colleges are often categorized.

Cohen’s retreat from the Republican label is perhaps representative of the identity crises that come with personal and political identities being more intertwined than ever, particularly among young people. Political polarization and tribalism have been widely cited as partially responsible for the contentiousness of the 2016 election and the months and years leading up to it; that polarization is perhaps intensified by the passion and proximity of college campuses.

For Weinberg sophomore Joseph Lamps, the transition to college meant finding himself in the majority-held political belief system for the first time. Lamps grew up outside of Minneapolis, where he attended a conservative Catholic high school. By his junior year of high school, he openly identified as liberal and as an atheist, adopting the role of a firebrand against a cultural backdrop of deeply held conservatism.

But at Northwestern, Lamps’ political leanings fall well within the mainstream of student beliefs. He champions personal freedom and civil liberties as well as a “robust” social safety net, aggressive action on climate change and growing economic inequality, and campaign finance reform. While he considers himself to be quite liberal, he is ambivalent about the ideology of progressive leaders like Bernie Sanders.

“Ideologically, Hillary’s gradualism is how you get policy done,” Lamps said, “even if Bernie’s ideas would be great if they could be implemented, which I don’t know if they could. I’d like them to be. I voted [for Bernie Sanders] knowing that the primary was basically already decided. If I could appoint a president, I wouldn’t appoint Bernie Sanders to the presidency. I’m not sure it was the right choice.”

On the other side of the aisle is Drew Zbihley, a freshman neuroscience major from Pittsburgh. Growing up in the swing state of Pennsylvania, Zbihley said he encountered people of a variety of political beliefs at school as well as within his family. Zbihley identifies as a moderate Republican.

“I wouldn’t say I’m super conservative,” Zbihley said, who voted for Trump in November.

One of the foremost considerations in casting his vote, Zbihley said, was the candidates’ attitudes toward the Hobby Lobby Supreme Court case. For Zbihley, who is also Catholic, issues of religious freedom and exemptions from birth control mandates are a crucial political issue.

Donald Trump, for all of his bluster, vulgarity and womanizing, may seem like an incongruous choice for voters like Zbihley, who champions conservative social values. Trump did indeed lose many such voters in the primary, including Zbihley, to Texas senator Ted Cruz, and Zbihley noted that his vote in November was not without reservation and significant disagreements with Trump. He agrees with Cohen that hiding one’s vote for Trump for fear of backlash is a common phenomenon.

“I’ve hidden the fact [that I voted for Trump],” Zbihley said. “I try not to bring it up, but at the same time, if people are going to ask me, and they really want to have a political discussion civilly, I will gladly engage.”

For sophomore sociology major Nat Vega, far-left politics have been a part of everyday life since childhood. Vega also grew up in Pennsylvania, and was raised by a single mom who became involved in progressive politics and activism when Vega and their sister were young. Vega describes their mother’s involvement and parenting style as an early political influence.

“She wasn’t super strict with me or my sister, she basically let us be our own people, and she let us know that that’s what she wanted for us – to think for ourselves," they said. "And as I began using the internet more, I got into social media and started learning a lot of things from other people, learning more about progressive politics.”

Vega describes themself as a radical and anti-capitalist. While “pro-communist as a concept,” they say that the communist principles in which they see merit are not achievable without focusing on decolonization.

“You can’t take what we have and convert it into communism without realizing that we’re on stolen land, and divvying up power,” Vega said, “Actually recognizing the people whose land this is, and giving them the primary political power.”

Vega’s primary policy concerns include LGBT and race-related issues, environmentalism, anti-capitalism and prison reform. They struggled with the decision of whether or not to vote, knowing that neither major candidate represented their views, but ultimately decided to vote for Hillary Clinton. While they felt torn over the decision, Vega said they would have likely felt more guilty had they not voted at all.

Vega said that coming from a low-income background informed their perspective on economic issues, as they saw the harsh reality of capitalism’s impact on those in poverty first-hand from an early age. They note the emotional impact that students’ lack of perspective towards the experiences of low-income people can often have, recalling a moment in their political science class when a classmate made comments about poor people needing to “just work harder and move up in life”.

In an environment where Facebook is fertile ground for political statements, in which it is typical to know who all your friends voted for, and where the issues that matter to us all feel so urgent and elicit such passion that relationships can falter under the strain of opposing views, being outspoken about one’s political views can lead to a mix of affirmation and stigma. For Zbihley, fear of political backlash was a cause for concern at the beginning of his freshman year; however, he has found the majority of his friend group to be open-minded, despite being mostly liberal.

“I’d say a majority of my friends, we don’t talk about politics that often, but the majority of them are Democrats, actually, and I get along great with them,” Zbihley said. “When I first came to campus, I felt really ostracized for my beliefs, but I’ve kind of opened up to people, not necessarily in a political way, but in a person-to-person way, and I’ve become more comfortable with my position on campus.”

His experience, however, has not been entirely comfortable.

“I’ve been in circles where people openly, without knowing the identities and backgrounds of who’s in the group, will just blatantly talk down on Republicans and Republican thought,” he said, “but there’s also times where people see both sides of the argument, so it really depends on the situation.”

For Cohen, the experience of trying to discuss and debate with those who may disagree with her has been one of disappointed and at times harassment.

“I’ve been told to my face that I don’t matter,” Cohen said. “I was told to my face that my argument is invalid because I’ll be offended when people call me a racist. That I don’t matter, that I shouldn’t exist, that no one should listen to me, that no one has to listen to me…basically, I just get dehumanized a lot.”

Unlike in high school, Lamps said he doesn’t experience social stigma surrounding his political beliefs at Northwestern, which he attributes to his position within the mainstream. But he tries to engage those from across the political spectrum in discussion and debate as often as possible, both in the lobby of his dorm where he spends his evenings chatting and doing homework with friends and at Political Union and Philosophy Club meetings.

Cohen notes that in spite of the criticism of her libertarianism on campus, she has been able to maintain relationships with people across the political spectrum. Groups like College Republicans are intended to be a space for a wide variety of political identities, she said. Outside of their core conservative demographics, liberal students sometimes attend meetings to explore other perspectives, which the group welcomes.

“We didn’t want the implication to be, ‘to be a member of this group, you need to support a particular candidate,'" Cohen said, “because conservatism is so fractured, we want it to be a space for anyone who identifies as any string of conservative.”

Zbihley noted that he invites civil discussion with those on the other side, and that he often understands the anger and frustration that more liberal students feel towards Republicans. “I agree with a lot of what Democrats and the left wants to do,” he said. “I don’t necessarily agree on the means to get there, but I feel like there’s a lot of things and a lot of common ground in between us.”

It is hard to find a single policy issue on which the four are aligned, despite significant overlaps between the opinions of individuals. What they do share is the intertwining of political identity with other segments of identity; Zbihley’s politics are closely intertwined with his Catholic faith, while Vega’s political identity crucially intersects with their race, gender and sexuality. Lamps’s political beliefs are similarly informed by his passion for science and philosophy.

As far back as 1961, scholars have theorized about the important role personal identity plays in determining political ideology. Lucian Pye, a political scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, stated in his paper that "the dynamics of personality development tend to emphasize precisely those theories which are basic to any effectively communicated political ideology." It is clear that, at least for these students, the labels by which we categorize our own and others’ politics present an incomplete picture. Beyond labels, party registrations and cast ballots, these students are simply individuals with greatly varying visions for their country and their society.

Perhaps the common assumption that Northwestern is a politically homogenous campus has merit — or maybe we assume a lack of political difference around us simply because having conversations across those differences is difficult. In the Venn Diagram between Zbihley, Cohen, Lamps and Vega, the willingness and ability to speak openly and honestly about their beliefs at a time when such discussions are unprecedentedly daunting may be the sole thing in the center — but that’s a start.