Graphic by Savannah Christensen / North by Northwestern

Sitting on the curb directly across from this towering building, beside a Publix shopping mall, I am taking notes on my phone. I am backdropped by a violet bruising sky, and little children chasing each other in the turfs of grass. A line is snaking around the block beside the building, where around 60 people are shaded from the wet heat that will inevitably arrive by noon.

“Get in line or get in your car,” a security guard yells at me from across the parking lot.

I am watching the sun rise over an U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement center for the second time in a week. I am not undocumented. I am a natural-born U.S. citizen, but I am told to get in line.

This isn’t an immigration story.

I’ve read those before, and despise most of them. I’ve read enough weak portrayals of immigrants: crying, oppressed and stripped of agency for a lifetime. Every time, I am forced to imagine my parents written into small and fragile versions of themselves. This summer I was pushed into writing one of those immigration stories by my bosses at the publication I worked for. As a Latina student reporter, I always saw my hispanidad as something I inherently knew would affect my career options in the future. That reality felt distant and intangible. Now I can’t seem to shake my summer experiences from my everyday pursuits. Everywhere I go, I am reminded that I am just a Latina reporter.

It started off small.

“Can you help this reporter translate a four-hour interview for her feature because she doesn’t speak Spanish?”

I was happy to help and that might even be an understatement. I was excited to be useful and actually needed in the newsroom. I slipped on my headphones and got to translating. I had no experience with being a translator beyond typing professional emails for my mom, but my fingers flew across the keyboard nonetheless.

I was later asked to accompany another reporter on a trip to translate for their feature. They were covering a primarily Cuban community and needed to communicate. I was terrified to knock on doors and proceed in real-time translation, having never knocked on doors for interviews nor professionally translated. But I agreed and I’m still glad I did, after a day of heavy humidity and tireless walking, I felt accomplished. I never got paid for this work.

Then came the stories.

I pitched stories about the Latinx community because it’s what I know. Being back in my hometown, I was able to hear about Venezuelan journalists fleeing their country for the U.S. through a family friend that was connected to the community. I knew about what was happening in the neighborhoods I grew up in. I could go to rallies and understand what protesters said in Spanish. I could communicate and listen to them. In the cultural hub that is my hometown, you need to deliberately avoid the Latinx community to keep from covering them. There are only so many white people available for stories, yet every quirky white man above the age of 50 was covered at this publication. Whole cover stories were given to these white men that did little more than exist to deserve that kind of coverage.

My stories were looked over. I did them anyway. I expected to be ignored as an intern, brushing off the office’s apathy as something every intern experiences. But as the summer unfolded, I realized the problem was much bigger than that. There was a common thread in the coverage done by this publication: it was whitewashed. No one wanted a Latino on the cover. No one spoke Spanish. If there was a story that primarily involved Spanish speakers, I was told by reporters they simply wouldn’t do it because they had no way to communicate.

“You have to write a big story before you leave,” my editor told me one afternoon. My ears perked up and my mind ran with ideas. I had a little over a month left before my last day.

What if we examined the neighborhood Moonlight was based off of (that was largely forgotten after last year’s Oscars) and the organizations working to make life better for students there? Or how about the shark tagging expeditions university professors take civilians on as part of research? I could go out with them on the boat! How about the roots of santeria in a city where you can find bags of dead chickens on four-corner streets on any given day?

“Let’s make it something Hispanic, since that’s what you’ve been writing about,” he finishes.

Something Hispanic. That’s what I am in their eyes. I am someone Hispanic.

I nodded encouragingly. I’ll write something Hispanic. I’ll write the most damn Hispanic story they’ll ever read if it meant someone would finally pay attention to the stories I was writing. What he failed to realize was I had already written a big story. I spoke to over 10 Venezuelan journalists that escaped their country, fleeing death threats, bombings and kidnappings to pursue reporting in the city. That was big. And it was big because I pushed it to be, but it could’ve been a longer, more in-depth story. I wrote a profile on the first Afro-Cuban woman owned cigar brand. It could’ve been bigger. We could’ve examined Afro-Latinidad and the lack of intersectionality between the Black and Latinx communities in the city.

Later that day my other editor came with the pitch. The immigration story pitch. A lawyer had tipped him off saying the conditions of the undocumented immigrants waiting in the ICE center lines were inhumane. Pregnant women were forced to stand in the rain and heat, causing many to pass out. No one could sit, take breaks or drink water. The lines reached around the block, with lawyers given preferential treatment for parking.

I was appalled. I called all the lawyers I could find, and everyone was corroborating the story. The next day I drove an hour away from my home and two hours away from the office to see it for myself.

The line was short. People were taking water breaks. They were encouraged to take turns in the line to get some air conditioning in their cars. I had waited in a more brutal line for Knaus Berry farm cinnamon rolls on any given day.

When I reported back to the office the following day, I told them it was a nonstory. The story was the abuse and the abuse wasn’t happening. My boss told me to talk to people in the line. We wanted their anecdotes about why they’re there waiting. I told them it was a sensitive topic, too sensitive to just bombard people in a line for, but they insisted. I repeatedly told them it was a nonstory, we don’t need more crying immigrants. They insisted.

Later that afternoon I sobbed in the bathroom stall. I was being forced to write the immigration story I had spent my entire life hating.

I spent the following month driving an hour to the ICE center and two hours back to the office weekly, multiple times a week. I met activists, immigrants and families that had been torn apart. I heard people cry and laugh. I dealt with the ICE officers repeatedly asking to see my papers. I formed a connection with this place.

I was reluctant to push people for stories I knew would hurt them to relive. I have sat through enough dinner conversations where my mother cries over her food, remembering the torture she lived through back in her home country. I don’t want to see my mother in their eyes.

That same month, my boss tells me I am too shy and quiet to be a reporter. All I do is nod.

When it came down to writing the story, my boss mocks the women and children sharing the stories that I didn’t want from them, but he demanded. He mocks their tears and blames it on him being “a cynical motherfucker.” I stare at him in response.

The story is cut down into numbers and statements, not the faces and people I spent a month speaking to. The story is never published. I get emails from lawyers and texts from activists asking when the story will go up and I leave them unanswered because I am too ashamed to admit that I used them. I am too ashamed to admit that I too feel used and left for the abandon.

When I get to school, everyone asks how my summer was. I am torn between lying and burdening people with the truth. I find middle ground.

“It was OK.”

The truth is even now I am ashamed to write this. I could’ve spoken up more. I could’ve been more forceful with my interviewees at the ICE center. I could’ve written more stories that weren’t about the Latinx community. I run through the scenarios in my mind.

I am ashamed that even more than a month past my last day of work, I still think about what happened all the time. I still question all the journalism I do. I still question whether I can do this for the rest of my life. I live for journalism: talking to people, asking questions, writing stories – even the stories we all hate to write. But I cannot imagine muffling my cries in the bathroom stall during my lunch break for the rest of my life.

When my boss told me I was too quiet for this profession, I believed him. I believed them when they implied all I had to offer was my Spanish and hispanidad. I believed them when they pushed aside my stories as trivial.

But I have sat for hours, and gotten people to open up to me about the stories they don’t tell a soul. I listen more than I speak. I know how to get what’s meaningful out of a person. I know my strengths when I see them. And most of all I care, a lot, about everyone and everything. I am compassionate about the stories that I’ve never experienced. I’m learning but I’m a damn good journalist.

I was so ashamed that I wanted to keep quiet. Don’t stir the pot. People suggest I report them. What did they really do to me? People suggest I email them, ask them to publish the story. Everyone has a suggestion, but just the thought of contact sends me 100 steps back in the mental recovery I am making.

I am afraid to write this. I am afraid no one will believe me. I am terrified all of this is an overreaction. But I don’t want to be silent anymore. There is no winning in silence. And maybe being loud and angry won’t bring a victory either, but I do not come from a line of women who keep their mouths shut when they’ve been treated unjustly.

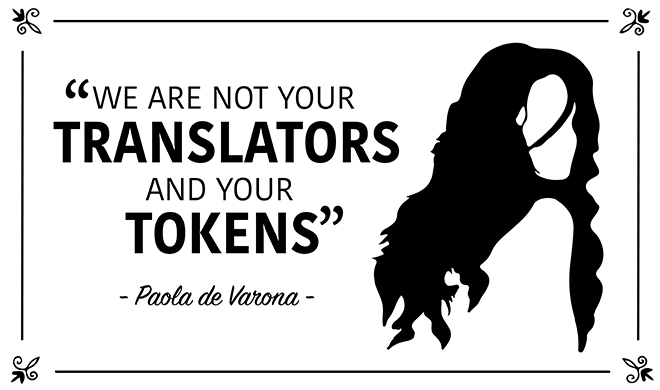

Latinx journalists are not your immigration reporters. We are not your translators and your tokens. Journalists need to do better. It is not our job to educate you. I love writing about the Latinx community, and I love being invited into their homes. I love the warmth that comes with their stories. But I also love writing about a variety of subjects, from the politics of fashion to quirky profiles on interesting individuals. I am trying to learn how to cope in healthy ways with my experience in the summer. How am I simultaneously grateful for the opportunity I was given, which I felt like I didn’t deserve in the first place, while also aware of the horrible ways I was treated? I am tired of feeling like I don’t deserve the opportunities I earned through hard work.

The backlash for writing this is unclear. But every time I doubt whether I should air the ways in which I was unjustly treated as a Latina reporter I think back to my grandmother, Yaya, lying in a hospital bed just days before she died. She was 98. The doctor came into the hospital room and, seeing that my grandma said nothing, turned to my mom asking her whether my grandma talked. My grandma responded:

"¿Si hablo? Hablo, grito, y meto patadas. ¿Se creen que yo estoy boba?"

Well Yaya, I learned from the best.