In 1967, Bill Walker painted “Wall of Respect,” the iconic South Side mural showcasing Black heroes. Fast forward 50 years, and now he’s the subject of the Hyde Park Art Center’s exhibition Bill Walker: Urban Griot, on display until April 8. Juarez Hawkins, artist, Northwestern alumna and Chicago State University lecturer, talks through the process of curating a space dedicated to Walker’s grittier, lesser-known print works.

Hawkins stands with two of her favorite Walker works. Photo by Alena Prcela / North by Northwestern

NBN: What inspired this undertaking?

Hawkins: I was concerned with the idea that seminal figures [like Walker] could easily just be whitewashed into history. If this were Matisse, there’d be no question of the need to preserve. These guys could die and fade into obscurity and we’d never know they were here. And because he’s not doing work to buy and sell, he’s not necessarily getting in museums. Chicago State had this body of work just sitting in a closet somewhere. It’s like, “You guys, it’s the 50th anniversary of the ‘Wall of Respect.’” What better time to put it out here?

NBN: Why did you decide to relegate photographs of his murals to one small section of the exhibition?

Hawkins: A lot of people only know Bill Walker for the“Wall of Respect.” We didn’t want to beat audiences over the head with that. I did this to give a full sense of how expansive his career was. He’s in here. He’s knee deep. He’s painting murals all over the city, then climbs down off the scaffold and does all this stuff [gesturing to the three print series that make up the rest of the exhibition].

Photo by Alena Prcela / North by Northwestern

NBN: What’s the most interesting thing you learned as you were curating?

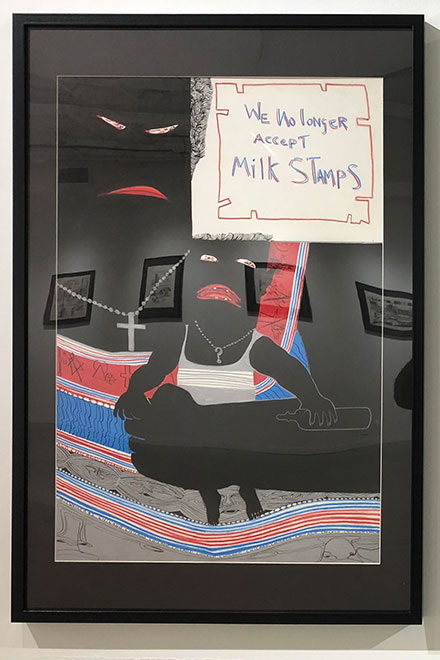

Hawkins: The more and more I look at them, the more and more things pop up. I could probably spend the rest of my life trying to decipher. I started looking for the first time [at “Red, White, and Blue 3,” a piece showing a mother and child]. I’m like, “Wait a minute. There’s a lot of signs here. These are gang symbols.” Well, why was [the mother] wearing gang symbols around her neck? And then on a tour someone said, “In these project environments, if you didn’t have any cash you can maybe go to the local gang leader and hit him up for a loan. If you needed to feed your kid, that was an immediate way to get funds.” I’m just trying to connect the dots and so this young lady schooled me on it.

Photo by Alena Prcela / North by Northwestern

NBN: A lot of Walker’s works focus on Black community. How does that tie into the community programming you developed to accompany the exhibition?

Hawkins: There could be a little something for everybody. If you don’t want to do an academic panel you can come to a film screening or a concert or an art-making day. The mainstay audience are people who had been there, so we’re talking people in their 60s. But we were also able to bring in teachers. And so they can go back to their communities and work up their own curriculum. I had concerns over so many depictions of violence. But the curator in me is like, “Stand by the work, dammit!” Our kids need to see this. I feel like we’ve spread the gospel.

NBN: Now that you’ve done all this, what’s next?

Hawkins: Finding a tour for it. It’s been a great adventure. I want to see if there are other museums who want to take it on.

NBN: How will you continue to carry Walker’s influence with you into your own artwork?

Hawkins: I’m fascinated with what the man can do with a pen. Even if you can’t hang with the violence, stay for the composition. It’s like, “Man! How do you depict a fight? How do you depict a stabbing?” The compositional stuff has got me really juiced up. Keep an eye out because this show will come down and I’m going to pick up my paint again. I’m curious to see what I come up with next.

Photo by Alena Prcela / North by Northwestern

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.