When Aniket Panjwani moved 3.3 miles from campus last fall, he absolutely hated driving his old Toyota Camry in rush hour traffic every morning. After a half hour or so behind the wheel, the Ph.D. student in economics would finally arrive at the Kellogg Global Hub. He struggled to find a parking spot, even though he was paying $552 a year for one.

So Panjwani decided to make his own electric bicycle, a.k.a. “e-bike,” to save time and money. Since the new Sheridan bike lane opened at the end of October, he said, it’s more convenient and safer than ever to get to his office. He didn’t need to use his advanced math skills to see that building his own e-bike for under $1,000 would almost pay itself off by avoiding just one year of gas and parking.

On his e-bike, Panjwani cut his travel time down to around 20 minutes. He can ride to the front of cars at red lights and dodge construction.

“To kind of rationalize it in my head, I used this economic thinking, but really, the main reason I’m doing this, even if I didn’t save any money, it’s just so fun to ride,” Panjwani said.

When he took his friends to the Lakefill to test his creation, he said one of them laughed for a full two minutes after hopping off. “Twist on the handlebar, you just suddenly start blasting off and going really fast," Panjwani said. "So it sort of blows your mind the first time."

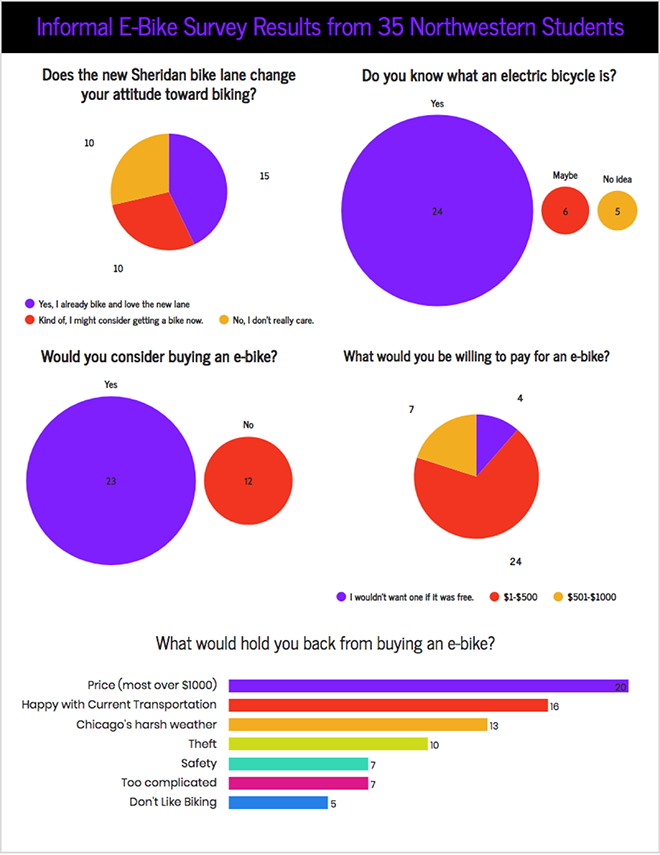

Although Panjwani was one of only two Northwestern e-bike riders I was able to track down, in an informal survey of Northwestern undergraduate friends and acquaintances, 15 of the 35 total respondents said they already use a traditional bicycle and love the new protected lane lane and another 10 said they might consider getting one with the new infrastructure.

While an e-bike looks like a normal bicycle, it acts as a moped or even car replacement, hitting a top speed between 18 and 28 mph. Most e-bikes in the U.S. are pedal-assist, meaning the rider needs to work for the motor to kick-in, but some, such as Panjwani’s creation, include a motorcycle-like throttle.

Ravindra Kempaiah, a nanotechnology Ph.D. student at University of Illinois at Chicago and the Guinness World Record holder for the longest journey on a motorized bicycle, said raising awareness about e-bikes as an alternative mode of transportation motivated him to break the world record. He said that if he can ride 5,100.90 miles in 34 days on a pedal-assist bike, averaging over 150 miles a day, “A 10-mile commute should be easily doable.” With e-bikes, Northwestern students could easily commute to campus from distant apartments rather than waiting to take the shuttle.

"E-Bike Ninja" Ravindra Kempaiah outside Norris after a 16 mile trek from UIC.

Photo by author

The e-bike can also hold cargo. Kempaiah said he can easily carry 50 pounds of groceries on the back of his e-bike, which means that students could easily haul a heavy backpack when scrambling to class or load up at a grocery store. “You’re not looking at a bicycle, you’re looking at a 90 percent car replacement,” he said.

A campus e-bike trend would be in line with the recent worldwide increase in e-bike sales. There are currently 250 million e-bikes in the world, with 1.6 billion projected by 2042, according to the 2017 ExtraEnergy Pedelec and E-Bike Yearbook. Kelly Goldthorpe, director of marketing and rider experience at Divvy, Chicago’s bike share program on campus, said e-bikes are “top of line on their product sheets radar,” as they are constantly trying to get more people riding.

There’s no mention of e-bike restrictions in the City of Evanston Motorized Vehicle Ordinance or the University’s bicycle policy, so following Illinois law, e-bikes would fall under normal bicycle rules aside from sidewalks. Luke Figora, Northwestern Office of Risk Management assistant vice president, said there hasn't been a need for additional e-bike restrictions with so few riders, so the University is relying on existing state and local regulations. Northwestern Deputy Chief of Police Tommye Sutton said the University is “still assessing” the e-bike policy on campus. For now, e-bikers can use the bike lane and asphalt roads around campus, just not the sidewalks.

Only 69 percent of informal survey respondents knew what e-bikes were, but 66 percent said they would consider buying one after a brief description. Jeremy Larkin, a SESP sophomore and running back on Northwestern’s football team, didn’t know about e-bikes when buying his moped. If he had known, he said he “probably would have done an e-bike instead because it’s more efficient and cheaper."

Four Northwestern students with no prior knowledge of e-bikes had differing reactions after trying the same pedal-assist e-bike outside of Norris University Center.

Communication senior Zach Gold said it didn’t feel much different than a normal bicycle after the motor’s initial drive, so he probably wouldn’t consider buying one. But Weinberg freshman Justine Banbury felt like with one push she went three times as far as a normal bicycle.

Weinberg junior Madisen Hursey said if she could buy one today she would, even though she was initially hesitant to try it since she dislikes motorcycles and scooters. Her friend, Weinberg junior Stefani Amick, added that it’s even easier to balance than a normal bicycle because it doesn’t wobble in the beginning on a high gear, it just goes.

“If someone is in front of Norris asking if you want to try an e-bike, yes you do,” Hursey said.

Weinberg sophomore Sarah Nicholson loves relaxing on her $1,000 E-Glide after her cross-country team workouts and still getting to class quickly. Her dad bought the bike online from California, and when it arrived, he was so excited to open it, he slashed his leg with a box cutter and she had to take him to urgent care. “After we got over that, it really only took us about an hour,” Nicholson said about assembling handlebars, seat, tires, pedals and odometer with instruction from the manual and online videos.

Sarah Nicholson after assembling her e-bike before bringing it to campus.

Photo courtesy of Nicholson's father

Nicholson’s first night with the e-bike, she dreamed it was stolen, even with its U-lock, and panicked until she looked out the window and saw it on the rack. She is not alone, as 28.6 percent of the informal survey respondents marked theft as one of the factors holding them back from buying an e-bike. Nicholson said her fear of theft diminished over time, and she thinks many people don’t know they’re looking at an e-bike with expensive parts.

With the safety, health, cost and time benefits, why do more Northwestern students not ride e-bikes? Katherine Knapp, Evanston transportation and mobility coordinator, blames geography. At the annual National Association of City Transportation Officials this year in Chicago, she said a discussion point was that e-bike benefits are not fully realized in Chicago because it’s an exceptionally flat part of the country.

Still, Northwestern students have different buying options, both online and in stores. For a Northwestern student unsure about buying an e-bike online, Joe Marchfield, owner of Volton Bicycles in Skokie, just 6.3 miles from the Arch, said he offers models priced between $1,500 and $2,650.

For a student wanting to buy even closer to home, Wheel & Sprocket on Davis Street sells eight e-bike models between $2,800 to $5,000 in store and even more online. Eric Krzystofiak, general manager of the store, sold eight e-bikes this year — up from just one three years ago — but doesn’t recall selling any to Northwestern students. This could be due to the price point, with not one of the 35 Northwestern survey respondents willing to pay over $1,000 for an e-bike.

Meanwhile, Lenny Mattioli, owner of Crazy Lenny’s E-Bikes in Madison, Wisconsin, sold around 2,000 e-bikes last year. Of the 190 models Mattioli offers, he said most customers buy in “that sweet spot” between $1,200 and $1,700. Mattioli sells the Schwinn Tailwind model for only $400, which might be more reasonable to a Northwestern student with 67 percent of survey respondents willing to buy an e-bike in the $1 to $500 range.

Mattioli is considering opening a location in Evanston or Austin, Texas, in 12 to 24 months. He sees a market in Evanston, since he already has a considerable amount of customers from the greater Chicago area coming to his Madison location.

"If we could get a location near that wonderful bike trail along the shore of Lake Michigan…it’s just a joy.”