Photo by Karli Goldenberg / North by Northwestern

Students and members of the Northwestern community came together on Tuesday night to hear Women's Center Director Dr. Sekile Nzinga-Johnson speak about the intersection of the first-generation experience and socioeconomic class. The speech, which was part of a broader campaign called "I'm First," celebrates first-generation students “through storytelling and awareness-building,” according to the campaign’s website.

Nzinga-Johnson, who grew up in the housing projects, as both of her parents worked multiple jobs, considers herself “a Head Start kid” and “a free lunch kid.” As a first-generation, working class student, Nzinga-Johnson said she became more observant of middle-class and elite spaces, and more comfortable with protesting against them. One example Nzinga-Johnson gave focused on rules related to the different use of silverware and glasses.

“For me, I was like, there are people in my community that don’t even have forks. I am not about to use all of these different forks, or I don’t care about which forks that I use, so I took these small acts of protest,” Nzinga-Johnson said. “To this day I refuse to use the ‘right’ fork.”

Nzinga-Johnson also pushed against the notion that first-generation students sometimes do not complete their undergraduate degree because they “don’t have an example to show them how to deal with stress or expectations,” prompted by a piece she encountered while doing research.

“It’s this kind of framing that we should be concerned with because it’s not noting the structural and institutional barriers that might make someone not complete their degree,” Nzinga-Johnson said. “To say it’s about this one person not having the tenacity, not having the grit to survive, versus looking at all of the barriers that are in place that would prevent them from doing well is a problematic framing that I want us to throw away.”

Nzinga-Johnson said this type of mindset also contributes to the discussion about students dealing with "imposter syndrome," or feeling like a fraud despite all they've accomplished. She found issue with how the phenomenon portrays the individual as “having trouble adjusting to the environment” instead of something that is “imposed upon” working class and first-generation students.

“It is the host culture that surveils, identifies and labels an imposter when it feels threatened. It is the system that is the syndrome and needs the intervention,” Nzinga-Johnson said.

Despite discussing the ways in which academic institutions tend to burden working class and first-generation students, Nzinga-Johnson said that Northwestern is making progress, relating today’s increasing numbers of working class and first-generation students to the goals of the 1968 Bursar sit-in.

“Today we continue to meet the Black students’ demands of the 1968 Bursar’s takeover, one which was to accept more working class students and support them financially. 16 percent of our students are working class, and 10 are first-generation,” Nzinga-Johnson said. “We are striving to be a better Northwestern.”

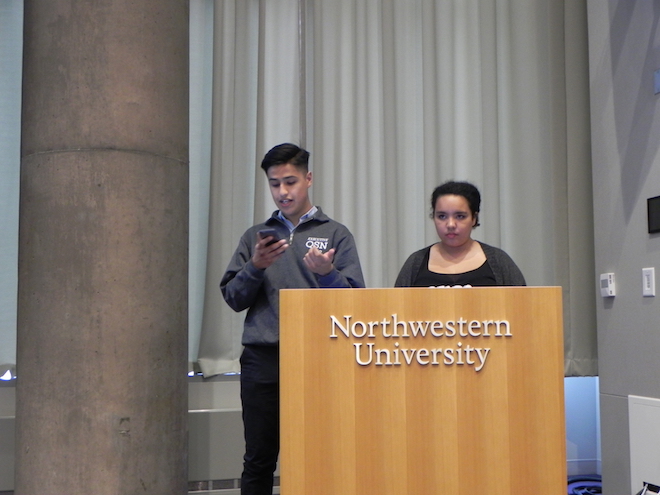

However, Christian Reyes, co-president of the Quest Scholars Network (QSN), an organization that advocates and puts on programming for first-generation and low-income students on campus, focused on the importance of administrative accountability, and expressed frustration that only one administrator showed up to hear Nzinga-Johnson speak.

"I think that that’s kind of unacceptable considering that there are a lot of people that are first-generation that work on campus, and I find it weird that they wouldn’t be here,” the SESP junior said. “I’d like to see some action behind the words. I know that Northwestern is striving from 20 percent [of students be Pell Grant recipients] by 2020. I don’t want them to just say that and not actually support, and show up, and do work with us, so I want to see more administrators at our stuff,” Reyes said.