Every summer, they think about Ricky Byrdsong.

Each Father’s Day, thousands of runners gather in Evanston for the Ricky Byrdsong Memorial Race Against Hate. This year marks the 15th anniversary of the event started by Byrdsong’s widow, Sherialyn Byrdsong, after her husband was shot and killed in a hate crime near their home in Skokie. The money raised from the event benefits the Ricky Byrdsong Foundation and the YWCA of Evanston, an organization dedicated to eliminating racism and empowering women.

“It really is a gratifying feeling knowing the race has a legacy that is continuing,” Sherialyn says.

Before the race begins, Sherialyn steps up to the microphone to address the thousands of participants in the event she created.

“Normally, I just try to make a connection between what Ricky stood for as a person and why the race is important and that it continues to have relevance because unfortunately, hate crimes continue to happen every day,” Sherialyn says. “So people come to the race for a lot of different reasons. Some come just because they are runners and walkers. Others come because they remember Ricky, they remember the events of that weekend and it’s a way for them to commemorate that and renew their commitment to turn hate into love.”

Trimmy Stamell, the events and grants manager at the YWCA of Evanston, is already planning this year’s race. Her organization took over planning the race in 2009 when Sherialyn moved back to Atlanta with her daughter Kelley. Stamell anticipates a larger draw than the 5,300 participants who attended last June. The race’s goals have broadened to combat hatred in all forms.

“It’s not the most effective money-maker,” Stamell says. “But, it is a fundraiser. It’s a wonderful messaging tool for us. It allows us to speak to the issues that really are embodied in the message of this race.”

The course begins at Long Field at Sheridan Road and Lincoln Street and winds its way through Northwestern’s campus, prompting some students to get involved in the yearly tradition. The race is a reminder of the legacy of its namesake, a bittersweet celebration of the values of the Byrdsong family. It represents the story of the Byrdsongs over the last fifteen years, an emergence from tragedy into proud remembrance, a transition from horrific shock to muted understanding, an annual eulogy for a life taken too soon.

Ricky’s Murder

“I was just fucking horrified,” Ricky Byrdsong Jr. says.

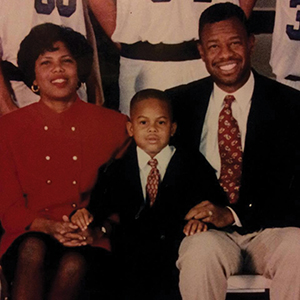

The now 23-year-old Missouri State University student went for a walk with his father and sister Kelley on the night of July 2, 1999 near their home in Skokie.

Byrdsong, the first African-American basketball coach at Northwestern, came home to spend time with his kids as he always did after work, seamlessly transitioning from the pressures of his professional life to his role as the father of three children, Ricky Jr., Kelley and Sabrina. “He was just my dad,” Ricky Jr. says. “He didn’t really talk about work at home. He was just focused on raising us and having fun with us. It wasn’t ever really about the job for him.”

Ricky Jr. says his parents valued school and church, ensuring that they went as a family every Sunday. Other times, he would go to Bulls games with his dad or play at the Northwestern gym. His older sister Kelley made it a weekly tradition to shoot hoops with her dad every week after church.

On July 2, Kelley was playing basketball at her neighbor’s house when Byrdsong wanted to go on one of his nightly walks in the neighborhood around the Skokie-Evanston border near their house. According to Kelley, he had first asked Sherialyn to join him but she needed to run an errand, so Ricky Jr. and Kelley came along instead.

Around the same time, Anya Cordell and her husband had taken sandwiches to eat at the nearby Central Park. Cordell lived on the Byrdsongs’ street but, at that point, had never met the family before. During their picnic dinner, the Cordells recall hearing what sounded like fireworks from local kids pre-emptively striking for the upcoming holiday.

Right by his father’s side, Ricky Jr. heard gunshots, then saw his dad start to go limp and fall. “I just went to the nearest house next to me,” Ricky Jr. says. “I called the police and watched my dad from inside the house in total shock. It seemed like it took forever for the ambulance to get there.”

“It was very scary,” Kelley says. “I had never had that kind of encounter with guns or violence. I didn’t realize what was going on until my dad was yelling, ‘Help, help.’ I rode my bike back home. My sister was in the house and I told her to call the police. I started crying and she called the police. It was just terror.”

Upon returning home from her errand, Sherialyn saw her oldest daughter Sabrina running down the street.

“She was the one who—when I got out the car—told me that Ricky had been shot,” Sherialyn says.

Benjamin Nathaniel Smith, then 21 years old, shot Ricky Byrdsong on the sidewalk at the corner of Hamlin Avenue and Foster Street in front of his two children. Smith was a member of the Creativity Movement, a white-supremacist group classified under the Neo-Nazi label. He had shot and wounded nine Orthodox Jews in Rogers Park before driving his blue Ford Taurus to Skokie. After he shot Byrdsong, Smith went on to wound an African-American minister in Decatur and to kill a Korean doctoral student in Bloomington. Smith took his own life during a police chase days later.

Byrdsong died from gunshot wounds in the hospital just hours after the shooting.

“No 8-year-old was supposed to see something like that,” Ricky Jr. says.

“I just remember being numb,” Sherialyn says. “It seems like the world stands still even though you keep moving. It’s just hard really for your mind to comprehend that. It’s definitely an unforgettable moment.”

Byrdsong’s Legacy

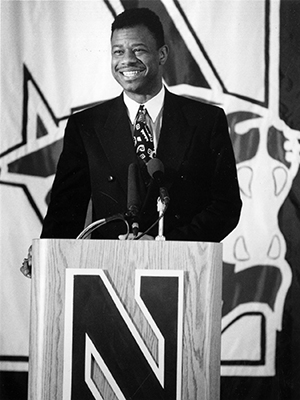

Ricky Byrdsong was the head coach of Northwestern’s basketball team from 1993 until 1997. On the court, Byrdsong had a mixed reputation, struggling to pull wins together for the team and known for a particular day when he let emotions get the best of him.

On February 7, 1994, Northwestern was facing Minnesota away, trying desperately to avoid their eighth consecutive loss. In the midst of impending defeat, Byrdsong grew so frustrated that he marched to the opposite end of the bench and isolated himself from the other coaches. He grew increasingly upset with the way the Wildcats were playing and he walked onto the court to make complaints to the referees numerous times. Byrdsong refused to join the huddle with the players and decided to turn management of the team over to one of his assistant coaches, Paul Swanson. He then walked into the crowd and took a seat in the stands until an usher requested that he move.

“He had told me before that game to make sure that I was listening to the game because he was planning to do something,” Sherialyn says. “He didn’t tell me what he was going to do.”

Sherialyn described Ricky as a risk-taker and says the incident was a coordinated plan to motivate his struggling team.

It was an isolated incident indicative of Byrdsong’s growing frustration with the organization. Aside from his role as Northwestern’s first African-American basketball coach, Byrdsong’s impact extends beyond the confines of the game.

In January 1995, during Byrdsong’s tenure with the basketball team, Henry Bienen took office as the new University president. He got to know Byrdsong as a coach, father and friend.

“Our team was really not a strong team to say the least,” Bienen says. During the 1994-95 season, the Wildcats went 5-22. In the following two years, they were 7-20 and 7-22.

In 1995, Byrdsong asked to extend his contract, but Bienen refused and released him from the position.

“I thought he was a person of dignity and grace,” Bienen says. “It’s not easy to be fired from your job. He understood that these things happen in collegiate athletics.”

Byrdsong took the firing as an opportunity to reprioritize his time, Sherialyn says.

“He just looked at it as a sign and a time to do some other things that he had always wanted to do, which coaching basketball had prevented him from doing,” Sherialyn says. “He had definitely wanted to be in the community more and do more things for high school kids, middle school kids. It really just kind of freed him up to pursue other dreams that he had.”

After Byrdsong was fired, Bienen says the two remained friends. The former president thinks his legacy was equally, or more so, defined by his engagement in the community. Players and students alike remember his dedication and optimism.

“I don’t know how much he influenced me on the court,” former Northwestern basketball player Nate Pomeday (SoC ‘99) told the Daily Northwestern in a story published a week after the murder. “But he was the first person besides my father to teach me to respect everyone I met. He was always putting everything he said into practice.”

After leaving his job at Northwestern, Byrdsong became vice president of affairs at Chicago-based insurance company Aon, where he developed programs for the corporation to participate in community service and reach out to underprivileged children, according to the 1999 story in The Daily. He would often lead tours for grade school children around the corporation’s office. In 1998, he organized 750 Aon employees to participate in a company fundraiser walk for pediatric diabetes research.

Aon’s founder and retired chairman Pat Ryan, who hired Byrdsong after he got fired from the Northwestern basketball coach position, spoke at the First Presbyterian Church memorial service, honoring the man’s values and inspiring ideals.

“Forget the court, forget the playing field,” Ryan had said, according to an August 1999 story in the Chicago Tribune. “You were an impact player in life.”

Healing as a Community

The day after his tragic murder, the Cordells opened their home to begin a neighborhood discussion addressing how everyone could cope with the recent events.

“We sat and we talked about what had happened,” Anya Cordell says. “It was totally shocking for this neighborhood.”

She says the conversation in her living room brought all sorts of different people together that wouldn’t ordinarily have spent time together. The following day, as the media began to swarm their street, Cordell finally met Sherialyn. The two of them discussed their plans, and Byrdsong says she planned on walking in the upcoming July 4 parade. Cordell assured her she would walk with her. There was a moment of silence before the normally jubilant affair began.

Then Cordell decided to start the walks. The nightly walks began at 8 p.m. and anyone in the neighborhood could join.

“It created this opportunity for people who wouldn’t normally connect to connect in a deeper way,” Cordell says. In the summer and fall of that year, two other hate-crime shootings in Los Angeles prompted more residents to participate, with attendance on some nights swelling to about 100.

The group would traverse the very sidewalks where Byrdsong was shot, discussing their feelings and holding silent vigils for the man they lost.

“It was a way to connect with other people who were also in shock, also grieving, also angry,” Sherialyn says.

The walks were emotionally challenging for everyone involved but showed the collective spirit that emerged in the face of tragedy. “I used to go on those with my buddies,” Ricky Jr. says. “I remember. I went on those walks. They were kind of sad.”

Ricky Jr. says it was hard to initially join the neighborhood in its collective mourning for his father, but he acknowledges the walks were healthy for everyone involved.

“I thought it was necessary for everyone to come together and wake up, which unfortunately was at the expense of my dad,” Ricky Jr. says. Currently studying communications at Missouri State, Ricky Jr. appreciates that his father’s legacy is kept alive, even if it means that he has to think about the night he died.

“As I’ve gotten older, I’ve kind of become more numb to the pain,” Ricky Jr. says. “But yeah, I think about it every day. Each year, it’s less painful I guess.”

Kelley, now 24, works as a youth coach and coordinator at the Atlanta-based educational program Create Your Dreams. She says she has coped with the loss of her father through deep faith. Ricky Jr. had left for college at Missouri State, while Sabrina was finishing her undergraduate degree in film and television at Clark Atlanta University.

“I don’t think about the shooting every day,” Kelley says. “I think about my dad every day. I can go a month without thinking about the actual shooting. But I don’t think there’s a day that goes by when I don’t think of my dad. I don’t get sad about it anymore. Eventually, you can use it to help people.”

Kelley says she feels bad for Smith, the man responsible for taking her father’s life.

“My heart breaks for him too,” Kelley says. “It’s like, what made him get to the point where he could take another life? I feel like if my dad maybe had a conversation with Benjamin Smith, he could have changed his life.”

It’s with this same grace that Sherialyn speaks to the crowd at the annual Race Against Hate, which Kelley, Ricky Jr. and Sabrina attend every year. “It’s awesome, because it grows every year and it keeps the legacy alive,” Ricky Jr. says. “It’s just good to see everybody having a good time and smiling. I think it’s awesome.”

This year’s race is a week before graduation, which Stamell hopes will encourage the Northwestern community to get more involved in the yearly Father’s Day tradition. Runners like Lisa Stein, a 47-year-old writer in Evanston, attend each year to join the community in their collective remembrance. Stein remembers the first time she ran in the Race Against Hate.

“For me, I felt like the atmosphere was very emotional,” Stein says. “When his wife spoke, everyone around me had tears in their eyes. And it just felt very important and it felt like the right thing to do.”

Until June comes around again, Kelley and her family keep their father in their thoughts, ensuring the legacy of a man tragically murdered never fades as the years go on.

“Each time there’s an opportunity to share the experience, I think it’s a good thing,” Kelley says. “I appreciate the legacy that my dad left and it just reminds me that we can always ask: What legacy we are leaving?”

Sherialyn lives by an adage she learned from her husband, a turn of phrase that guides her on a daily basis to love and to spread healing.

“His legacy is always about turning around the bad to get the greater good,” Sherialyn says. “He used to say that, ‘life is 10 percent what happens to you and 90 percent how you respond to it.’ And I think the 10 percent is the fact that Ricky was killed but the 90 percent is just the unifying impact it has had on our community.”

The Byrdsongs are continuing to respond, pounding the pavement in a perpetual race against hate.