Today, a stereotype of the South Side of Chicago as dangerous, Black and crime ridden persists, and can still be heard on campus and in the national media. But for Thursday night’s Unshackled NU talk, activist and academic Dr. Rashad Shabazz traced the history of mass incarceration to slavery, colonialism, and a war on drugs that became a war on Black people.

“This current mass incarceration drama we’ve seen over the last four decades started in early 20th century...” Shabazz said. “[came] with the evacuation of economic means of production and the belief that punishment and containment is the way you solved social problems.”

Shabazz’s speech marked the last event in Unshackle NU’s week of education on the school to prison pipeline. The group is doing a four-week campaign of seminars to rally support for a forthcoming petition to divest from private prisons. Their second week will focus on the impact of private prisons on immigration detention.

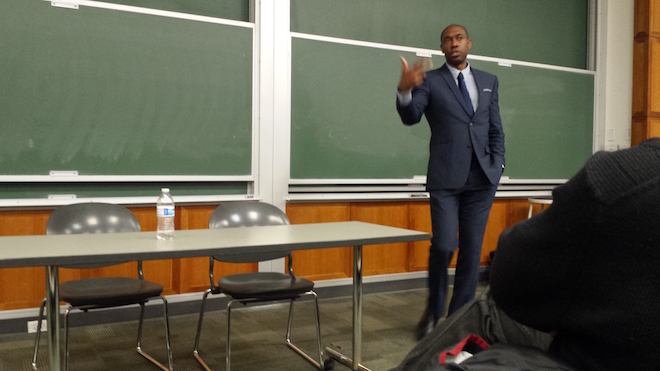

Speaking before a crowded group of students and student-activists in Annenberg Hall, Shabazz focused on dispelling the belief that mass incarceration is simply a matter of modern crime and policies. Since slavery, he said, Western society has learned how to punish through confining Black people.

“Antiblack racism is the landscape upon which the Western prison system was able to produce its punishment,” Shabazz said.

The legacy of racism exists today in the form of the largely Black concentrated areas of poverty.The prison system obtains a majority of its inmates form these areas. These areas don’t emergy by accident, Shabazz argued. Blacks moved north in the first half of the twentieth century to find work in industrializing cities, but racially restrictive housing covenants and threats of violence kept them out of white neighborhoods and cramped in small apartments and later public housing in narrow strips of land. When factories moved overseas in the 1960s, these areas that had relied on them for jobs began to struggle. That, Shabazz said, marked the beginning of mass incarceration.

“Rather than seeing the economic downturn and the forms of instability and responding to it in a way that fostered mobility,” Shabazz said, “Illinois and the federal government decided the best way to deal with the projects was to contain it.”

The federal government funnelled money for maintaining public housing into security, Shabazz said. The state bought up empty rural land and develop prisons on, providing jobs for many unemployed whites. Elevators, basketball courts, and swingsets deteriorated, while the state installed surveillance cameras, bullet proof glass and cages and upped the police force. Successive presidents imposed harsher penalties for drug violations, most of which went to Blacks despite widespread use among whites. In short, Shabazz said, the police state extended from prisons into the communities and schools.

“All those things that made life fun and interesting for young people was stripped away,” Shabazz said. “What became most important was security.”

And this was not for safety purposes, Shabazz said.

“The identification badges, the cages, the on-site courts were about the residents and keeping all the forms of instability that were existing there inside,” Shabazz said.

The result today is a system in which thousands of Black people in Chicago cycle in and out of prison, Shabazz explained. He drew a diagram on the board: a circle labeled “taxes” connected by a line to “state governments” to “prison.” He said it showed how state governments use taxpayer money to finance the prison industry, which profits off of punishing Black people, particularly the poor. Because the prisons fail to rehabilitate, they’ve created a system in which 30,000 people enter Illinois state prison each year, half of whom had just gotten out.

“The recidivism rate is 50 percent, which means shit don’t work,” Shabazz said, “Any institution that can’t maintain a C average is a failure.”

So what can people, particularly Northwestern students, do about it? Shabazz said there are policies that could bridge the gap created by a century of legal racial discrimination, such as a “subsidy to do the opposite” of racial segregation and inequality. It’s similar to the “Case for Reparations” Ta-Nehisi Coates has repeatedly put forward in The Atlantic.

But Shabazz also said people needed to the national ideology around crime from one of containment and punishment to restorative justice model that emphasizes social mobility.

“We have been lulled into believing that if you put up bigger walls and if you put more people that that will create safety,” Shabazz said. “And that’s just not true.”