Yongsung Kim wants to know if his project is “cool.” He’s sitting at his desk in the Delta Lab on the second floor of the Ford Engineering Design Center, where he has just finished describing his still-in-progress mobile crowdsourcing app called CrowdFound.

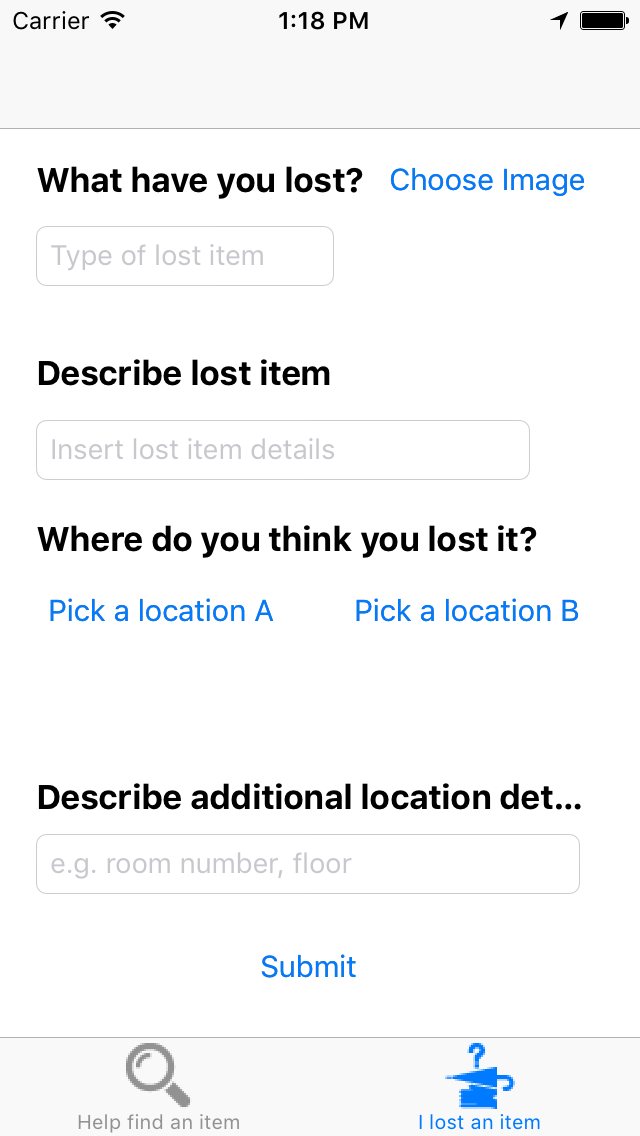

The idea behind the application is to create a system for users to find lost items while on the go through crowdsourcing, which provides a service – say, finding a misplaced belonging – through the help of a large group. In CrowdFound, users input a description of their lost items on a map, and the app notifies other users when they pass by the tagged areas. While testing the app, Kim found that users would go out of their way to find items and were especially willing while exercising.

CrowdFound operates on the principle that people take the same routes at the same time each day – walking, biking, running – and that communal pattern creates a resource Kim hopes to employ to complete minimal tasks.

“There is an opportunity there if we utilize [people’s] routines and then ask each of them to do small tasks with low effort in a small amount of time, then collectively we can reach a way larger goal,” Kim said. “For instance, what if we can ask crowds to find a lost child? That’s a lot more challenging than finding a lost item that is static.”

Kim’s work at Northwestern focuses on crowdsourcing, a term coined in 2006 by Wired writer Jeff Howe that plays on the term “outsourcing.” Drawing from the example of the ultra-cheap image sharing site iStockphoto, Howe defined crowdsourcing as when a company takes a function “once performed by employees” and outsources it “to an undefined (and generally large) network of people in the form of an open call.”

“Everyone has a little different definition, even among researchers,” Kim said. “I would say that [in] crowdsourcing, you request to a crowd, either known or unknown, and then they help you complete [a] task, either with monetary rates or voluntarily.”

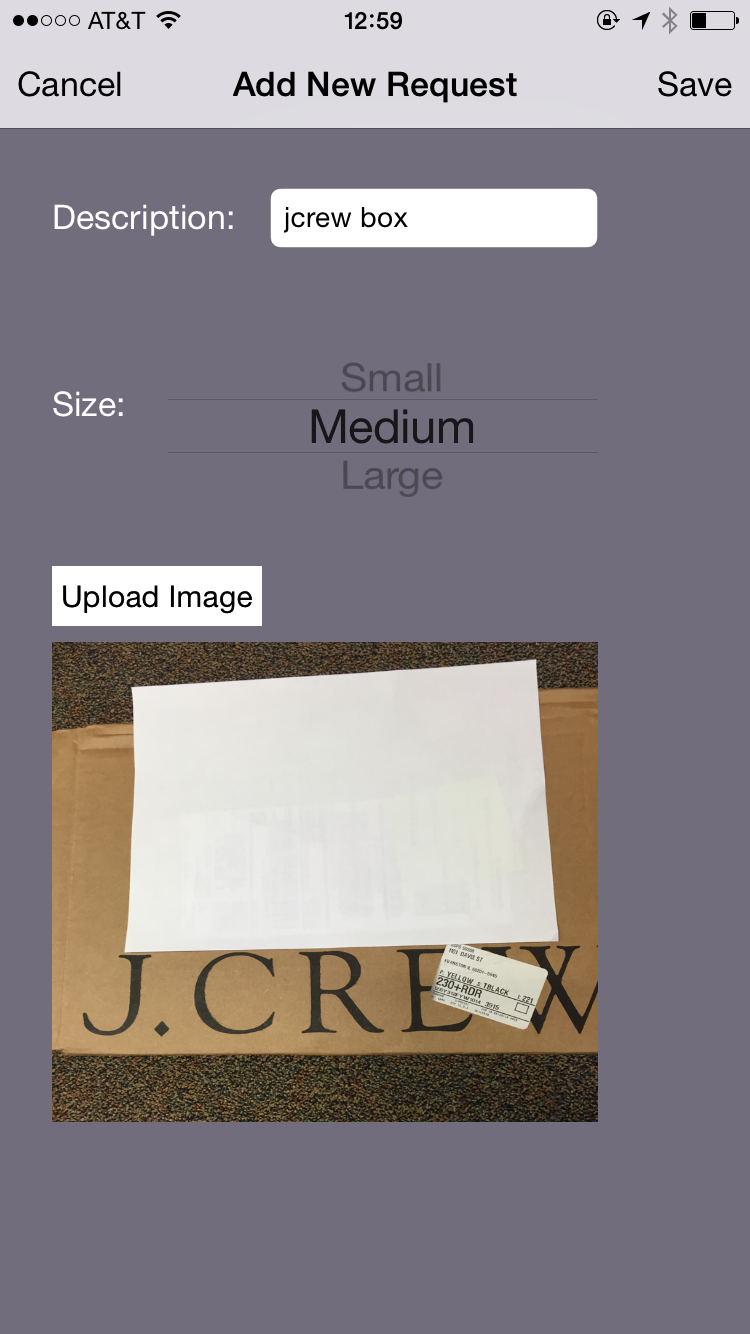

Kim is a second year Ph.D student in the technology and social behavior program, a joint program in McCormick and the School of Communication with a curriculum focused on computer science and communication. He earned computer science degrees at universities in Beijing and Switzerland before coming to Evanston in September 2014. He is developing another on-the-go crowdsourcing app called Libero, which runs on the same idea as CrowdFound: using the collective pattern of people’s daily routes to complete easy tasks. But the apps serve two different purposes. Libero collects package delivery requests from its users and routes those requests to other users who might deliver the package for them.

In a typical scenario, a Libero user will forward a notification email from a package center to the app to request a delivery. Another user, ideally from the same dorm, will receive what Kim calls a “just-in-time” notification when close to the package center. The user can choose to pick up the package by showing the email to the mailroom staff, then drop off the package at the dorm he is already walking back to.

The system relies on a certain degree of trust, which comes in part from reciprocity – you deliver my package, I deliver yours – and strong community ties. But from what Kim found while testing CrowdFound, crowdsourcing apps at Northwestern just might work, even if users have to go a little out of their way.