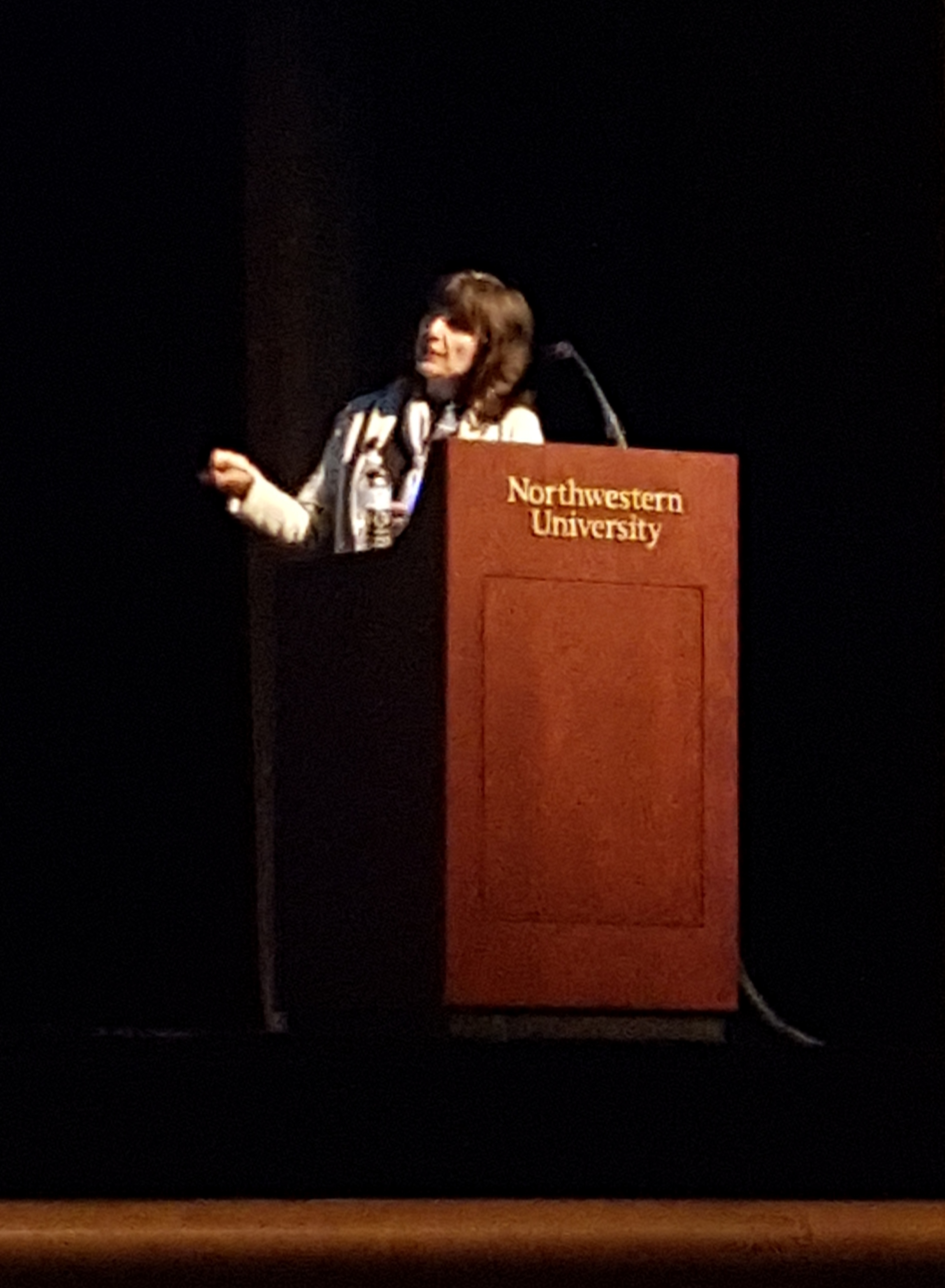

Photo by Carlyn Kranking

University of Chicago Professor and renowned astronomer Wendy Freedman gestures to a slide titled “Theorist’s view of the Universe.” Under the title is a black, empty rectangle. It is supposed to represent dark matter, a theoretical matter that has been confusing scientists for years.

“[This also] reflects our knowledge of dark matter,” Freedman said, eliciting laughs from her audience.

On Oct. 5, Freedman spoke to a crowd of Northwestern students and local astronomy enthusiasts about her work on the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), for which she served as chair of the Board of Directors from 2003 to 2015. Freedman hopes that the GMT will better track the expansion of the universe and the distribution of dark matter, among other things.

“I think dark matter is super interesting,” Medill sophomore Crystal Wall said. “The fact that … it’s such a substantial part of the universe and we have no clue what it’s even made out of...is one of the most interesting parts for me.”

The GMT, which will have 10 times the viewing power of the Hubble Space Telescope, may also observe supernovae and even help in the search for extraterrestrial life by detecting biomarkers such as carbon and ozone on exoplanets.

The GMT is a mega-project valued at over $1 billion, with funding coming from institutions in the U.S., South Korea, Australia and Brazil, as well as from private philanthropists. When completed in the 2020s, it will be 20 million times more sensitive to light than the human eye, and the apparatus will be only a few meters shorter than the height of the Statue of Liberty.

To give some perspective of the capabilities of the GMT, Freedman said that it would be able to resolve a theoretical candle on the Moon from Earth. (This scenario is theoretical, because a match would not be able to light on the Moon without oxygen.) By using comparisons such as this, Freedman was able to turn complex science and engineering concepts into ideas that were easier for people to understand, a practice appreciated by hobby astronomer Michael Sinner. Sinner came from the North Side of Chicago to listen to Freedman’s talk.

“I was afraid it was going to be too technical,” Sinner said. “It was really at a level that I think everybody could follow. … It was kind of like space for dummies. I really appreciated that.”

In addition to discussing her work on the GMT, Freedman talked about the structure and accelerating expansion of the universe. According to Freedman, 95 percent of the composition of the universe is unknown with about two-thirds comprising dark energy, the leading cause of the expansion of the universe, and about a third comprising dark matter, which is theorized to hold galaxies together. Stars make up only 1 percent of the universe and an additional 4 percent is made up of ordinary matter like planets and comets.

“It’s crazy to think of how small of a little piece of the universe we are," Wall said. "We just feel that we are so huge here on Earth when really we’re just this tiny, tiny little fragment of this entire universe, and it’s still growing."

Wall, a Northwestern student, was actually a minority in the audience. Most attendees were adults or families with a passion for astronomy. Evanston resident Ernie Norrman attended the lecture because he has been interested in astronomy since childhood. Norrman grew up in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, the home of the Yerkes Observatory, which is operated by the University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“A lot of my classmates’ fathers were involved in the observatory and were astrophysicists, and my own dad developed tiny equipment for the early space program," Norrman said. "But that’s all archaic now."

Like Norrman, Sinner has had a lifelong interest in outer space, though after traveling to Columbia, Missouri, to view the solar eclipse last summer, he began to follow astronomical developments more closely. Perhaps images from the GMT will rekindle someone’s interest in astronomy, just as the eclipse did for Sinner.

“I’ve always been involved casually with space. I had a telescope when I was a little kid,” Sinner said. “I still have that telescope. It’s still in good condition, and … every once in awhile on a summer night … I’ll bring out that telescope and start looking again.”