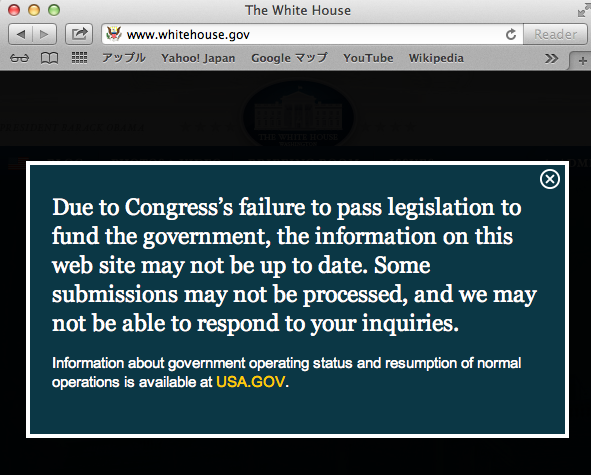

Monday night, Congress did something almost beautiful in its sheer stupidity. Faced with an ongoing battle over Obamacare, neither the Republican-controlled House nor the Democratic Senate proved willing to back down and compromise to reach a continuing resolution (or CR) that would fund the government for another year. Unlike a real budget, a CR merely maintains funding levels at where they were in the previous year. Democrats and Republicans would have to pass a CR and then sit down at the table again to work out a real budget. Instead, they shut down the government.

Democrats refuse to negotiate on the issue, saying that not only is Obamacare Supreme Court-approved and already the law of the land, but that they already offered concessions by agreeing to a CR at sequester levels, which means a smaller budget than Democrats wanted.

For Republicans, the issue is not about debating Democrats, but an intraparty clash. A hardline group of conservatives has managed to pull the entire caucus into a battle it did not yet want to fight. The answer to how and why this happened does not lie in Tea Party insanity or bitterness over Mitt Romney’s defeat, as you might cynically expect. Instead, the ongoing government shutdown has its roots in two recent successes of the Republican Party, those being their surprisingly successful obstruction strategy and their skillful redistricting in 2010.

First, it is important to understand that when Republican legislators are characterized as being the “party of no”, it is not a name that has been applied to them in contradiction of their actual policies. Instead, right-wing legislators set out from the very beginning of the Obama administration to work to counteract every piece of legislation the administration wanted to pass. This tactic was enormously succesful at poisoning the well against Obama's policies and fomenting grassroots support. By the time midterms rolled around in 2010, the billionaire-funded, locally-organized and Republican-affiliated Tea Party movement gained enough momentum and clout to push through a huge slate of candidates. High Tea Party turnout also meant good results for Republicans: The GOP gained control of numerous state legislatures, and consequently, of the decennial redistricting process.

Fast forward to 2012: The Republican Party has given itself a huge number of easily-winnable districts in otherwise shaky states, thanks to successful gerrymandering across the nation. Though Mitt Romney lost the election, and more votes are actually cast overall for Democrats, the GOP’s smart use of the redistricting process enabled it to retain control of the House. Numerous freshman GOP representatives, though, felt stung by the perceived “failure” of the 2012 election. To give the rank-and-file a new goal, Republicans decided on a new strategy: The more junior members of the caucus would fall in line on smaller issues like continuing resolutions and sequestration. Then, with the caucus unified, Republicans could use the upcoming debt-ceiling battle (which comes to a head on Oct. 17) to force the Obama administration to adopt the Paul Ryan budget, which is popular within the Republican caucus but which Democrats loathe.

Then Ted Cruz ruined everything.

Ted Cruz is the junior senator from Texas. Last week, in response to the end of the fiscal year, he wanted to speak about Obamacare, which came into effect this Tuesday. Cruz wanted to use the end of the fiscal year (which comes at the end of September) as an opportunity to revive the fight against Obamacare, by pushing the idea of a CR that would defund Obamacare. To this end, Cruz spoke for 21 hours on the Senate floor in a speech that blocked no actual legislation but brought attention to his issue.

Cruz was proposing two options: either Congress passed a CR that defunded Obamacare or the government shut down. Since Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid had already declared that the Senate would pass no CR that included any caveats about Obamacare, the likely option seemed shutdown.

Cruz got lambasted in the conservative media, and even the Wall Street Journal blasted “General Cruz” for his almost unilateral decision to force a showdown over the CR. Senior Republican senators like John McCain and Lindsey Graham hated it, and even Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell would not back him. Almost all of the criticism revolved around one point: this is a good fight to have, but not right now.

This is where past Republican victories came back to harm them. The first problem was the huge success of Republican obstructionism in 2009 and 2010. A group of roughly 80 Republican representatives, many of them freshmen, believes strongly in the ability of Republican obstructionism to win policy concessions and elections. The group, now dubbed the “suicide caucus”, decided to move ahead on the CR fight. It is easy to understand their gung-ho attitudes: when Republicans have used brinksmanship tactic like this in the past, as in the debt-ceiling talks of 2011 and the fiscal cliff crisis of 2012, Obama has generally backed down and given concessions to Republicans. With that in mind, rank-and-file Republicans pushed for Boehner to not back down on the CR issue, and in so doing, assured a shutdown.

The reason shutdown was assured is that Republicans gerrymandered too well back in 2010. They gave themselves districts that were solidly Republican and becoming less diverse. This is a sure-fire way for Republicans to consistently win a district for the next ten years. However, the deep conservatism has left Republicans open to a threat they were not expecting back in 2010: the potential of being knocked out of their seat by a challenger from the right. Incumbent Republican representatives John Sullivan and Jean Schmidt lost in the Republican primaries to challengers who successfully labeled the incumbents as RINOs, or Republicans In Name Only. Moderate Republicans now fear the possibility of being primaried in this fashion in their home districts, and quickly fell into line on the CR fight for fear of being seen as RINOs.

The rest of the story falls into place from there. If political orthodoxy is what saves Republican congressmen from being taken out in primaries, it is hardly surprising they chose to hold the line on the CR. Even though there were rumblings of a moderate revolt from within the Republican caucus, those plans quickly faltered when Boehner personally made appearances on the House floor to whip votes for the CR fight. Boehner fears a loss of unity within the party ahead of the debt-ceiling battle, and is not afraid to lean on the threat of primaries to bring moderates back in line.

All of this points to a shutdown that could go on for quite some time. At the time of writing, there are 19 Republicans willing to vote in favor of a clean CR, enough that they could reopen the government with support from House Democrats. Nevertheless, Boehner refuses to bring a clean CR to the House floor, for fear that the ensuing chaos in his caucus might endanger his dreams of a grand fiscal bargain. Here at Northwestern the pain of shutdown may not have hit us yet, but if Boehner continues to let the far right control the rest of the Republicans, things could start to look quite different indeed.