Photos by Claire Bugos / North by Northwestern

Few phrases have infiltrated American culture more in the past year than "Make America Great Again." Emblazoned on T-shirts, baseball caps and bumper stickers, it is a phrase that rallied 46 percent of America's voters to elect a man as red as a MAGA hat as president.

The power of Make America Great Again is in its ability to rewrite the past and persuade the American public that America, a country founded by colonists who settled on Native land, was ever truly great. To remember this country's past fondly is not just a privilege, but an act of intentional erasure; it is an act that willfully overlooks this country's more shameful histories in favor of a cultural amnesia that flatters our nostalgic sensibilities. However, it is these histories – told by people often relegated to the margins – which constitute this country's past, in all its glory and grotesque.

If You Remember, I'll Remember, the Block Museum's main exhibit for the season, is an exploration of these forgotten histories, rooted deeply in the personal. The show features six artists who use a variety of mediums, themes and historical inspirations. The main event of Saturday's Opening Day Conversation was a panel with four of the six artists, moderated by Janet Dees, the curator of modern and contemporary art in the global context. The discussion centered on the inspiration for the exhibit, the cultural and historical context of the artists' works, and how the exhibit's gravitas has shifted throughout its development.

Glass cases are lined up outside the main gallery. The main exhibit, titled If You Remember, I'll Remember, features contemporary American artists whose art conveys messages about civil rights, war and mourning.

Photo by Claire Bugos / North by Northwestern

Dees began working on the exhibit in 2016, following the national responses to both the white supremacist shooting at a Black church in Charleston, South Carolina and the Supreme Court ruling that legalized same-sex marriage. However, events that have transpired over the past year have given new meaning to the exhibit's vision. "The present is ever-shifting," Dees said at the exhibit's opening. "Moments leave us before we have had the chance to fully apprehend them."

And indeed, walking into the exhibit, there is an undeniable awareness of the new president's administration. It reminds us of the importance of remembering not only the America that was "great," but also the America that has and continues to imprison, forcibly assimilate and discriminate against its own people.

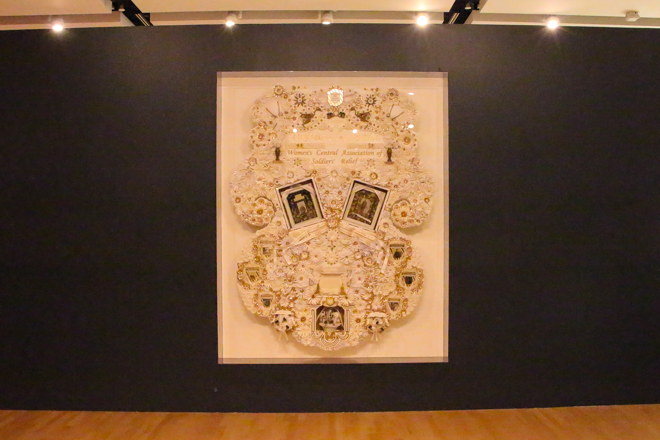

In the entrance of the gallery sits Dario Robleto's "No One Has a Monopoly Over Sorrow." The piece borrows from an oft-forgotten World War II tradition of widows assembling ephemera from the battlefield when bodies of fallen soldiers were so destroyed that they could not be brought back. The piece appears overflowing, dried flowers mixing with flowers made from widow's hair, metal-coated finger bones mixing with rusted wedding rings. The assemblage feels simultaneously futile – a desperate attempt to remember what is no longer there – and full of latent meaning.

This duality – between the pain of arousing a fraught national past and the necessity of remembering in spite of it – is palpable throughout this exhibit. Shan Goshorn's intricate basket weavings include "Prayers for Our Children," which features an image of Native students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (one of many Native American "forced acculturation" boarding schools founded in the late 1800s) literally interwoven with the words of Native healing prayers. Samantha Hill's "Herbarium" is an exploration into the life of the 16th Street Baptist Church, the center of community and civic engagement in Birmingham, Alabama, and also the target of a 1963 bombing by white supremacists. From McCallum & Tarry's "Exchange," a video piece challenging the history of anti-miscegenation, to Marie Watt's "Witness," a blanket embroidery highlighting Native potlatch traditions, the pieces in If You Remember evoke histories of erasure and violence, while also positing the simple act of remembering these histories as a mode of resistance.

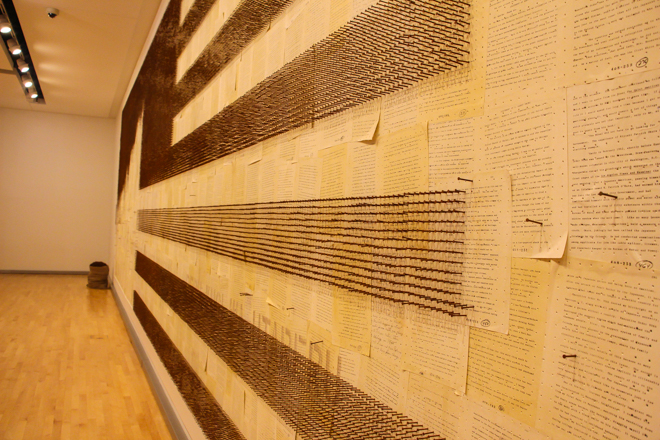

"The Nail that Sticks Up the Farthest Takes the Most Pounding," 2017, by Kristine Aono honors the memory of the 120,313 Japanese who were interned by the U.S. government during World War II. Her piece features 120,313 nails stuck in the wall in the formation of the American flag.

Photo by Claire Bugos / North by Northwestern

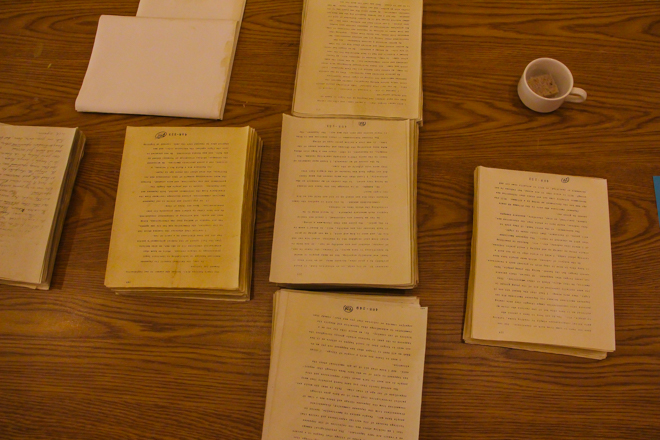

Perhaps the starkest of parallels with the present day arises from Kristine Aono's "The Nail That Sticks Up Farthest Takes the Most Pounding." In an installation that occupies the whole east wall of the gallery, copies of archival documents are wallpapered on a board and covered in 120,313 holes, some filled with nails in an American flag pattern, representing the number of Japanese people interned during World War II. The papers include transcripts from the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings, which included testimonies from those in the camps. "For many people, this was their first time talking about [internment]," Aono said. "It was very catalytic to have all these stories finally come forward."

The title of the piece comes from the phrase "Deru kugi wa utareru." "[It] is a Japanese proverb ... of acting as a group, not being the nail that sticks up the farthest, not calling attention to yourself," Aono said. The interactive aspect, where museum visitors add nails over the course of the exhibit's run, transforms the process of remembrance into a radical and communal act of calling attention to injustice, rather than remaining silent about it.

The proposition of the exhibit's title – If You'll Remember, I'll Remember – further underscores this collective responsibility, connecting "you" and "I" in a collective effort to recall more complex narratives that seem to be forgotten by our nation's highest office. The blatant disregard for history, used to justify discriminatory immigration orders and suppress freedom of the press, is evidence enough that remembering must not be an individual act, but a collective one. America was never great, but if we confront a past that still haunts our present, maybe it can be.