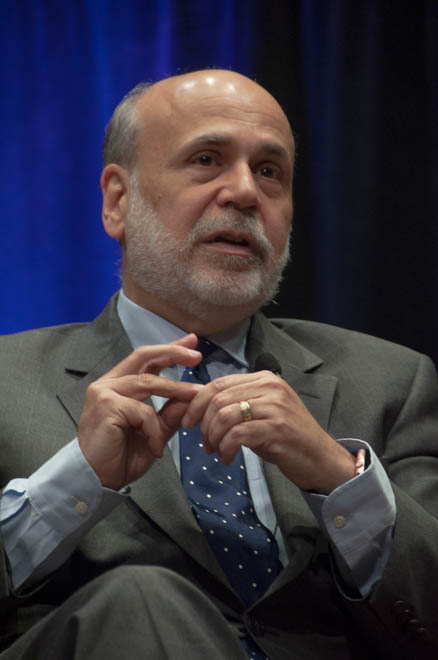

Northwestern students and faculty poured into Leverone Auditorium Tuesday night for the 2016 Susan Bies Lecture on Economics and Public Policy, eager to hear from the man who braved the 2007-2008 financial crisis: former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke.

Bernanke's lecture focused heavily on the Federal Reserve’s response to the Great Recession, as well as looking at the effects of new regulations going forward. Janice Eberly, Kellogg's James R. and Helen D. Russell professor of finance, led the conversation with Bernanke.

To start off the evening, Eberly commented on the event’s massive turnout. Once the seats filled up, attendees sat in the aisles and stood around the entrance. Some guests didn’t even make it inside.

“I think you and I are probably the only people who didn’t have to worry about getting a seat,” she said to Bernanke, drawing a laugh from the tightly packed audience.

However, the conversation did not remain lighthearted for long. Referencing the popularity of The Big Short, a movie critiquing the Wall Street negligence that led to the collapse of the U.S. housing market, Eberly asked Bernanke to explain the greater effect that subprime mortgage loans had on the domestic and international economy.

While they definitely played a role, Bernanke said “they just weren’t big enough by themselves” to be blamed entirely for the financial crisis.

Instead, according to Bernanke, “the subprime mortgages became the trigger for what was essentially an old fashioned banking panic,” like what you might see in movies like It’s a Wonderful Life or Mary Poppins.

When one part of the economy starts to flounder, Bernanke said, it ripples throughout the entire system.

“One of the reasons that panics are so destructive is that everyone kind of hunkers down,” he said. “The system comes to a screeching halt.”

Unlike The Big Short suggests, Bernanke said, it wasn’t that officials weren’t somewhat aware of the housing market’s underlying problems, it’s that they were unsure of how to approach solving them.

“In real time, you don’t know of course how bad ‘bad’ is going to be,” he said. “[We] didn’t want to do too much or too little.”

In order to respond quickly once disaster struck, Bernanke and the Federal Reserve team had to think outside of the box to stop the panic.

“We tried to do what I call ‘blue sky thinking,’” Bernanke said, comparing strategy sessions to scenes on the television show House, where Dr. House brainstorms possible solutions on a whiteboard.

“It was necessary to be creative because we were in a whole new world” relative to the past role of the Federal Reserve, he said. With the staff working 100 hours a week during the peak of the crisis, he said that everyone involved was personally committed to the project.

He compared working through the crisis to trying to control a car that is spinning out of control after hitting a sheet of ice. In that situation, he said, the sole focus is on how to safely stop the car from spinning, nothing else.

“During that time, what we all were doing was focusing all of our minds and attention on that problem,” Bernanke said, referring to the recession.

Although some of the team’s decisions faced backlash, like bailing out big banks, Bernanke said, he felt they were necessary to protect the greater system.

“I was very concerned that if the financial system collapsed, it would bring down the whole economy,” he said. The financial bailout was not “because we were trying to do Wall Street some big favor,” he said.

Looking to the future, Bernanke said it is important to see the bigger picture.

“When something rare happens like a plane crash,” he said, “when you go back and look at it, there’s going to be a lot of factors [that caused it].”

By examining these factors, it is clear that the system needs stricter regulation, Bernanke said. “Nobody was looking at the system as a whole.”

He said he is optimistic about the reforms to the financial district, especially when it comes to increased oversight. While “simply breaking up banks without thinking it through is not a wise thing to do,” Bernanke said, more regulations and requirements make “being big less attractive” and some banks even chose to dissolve themselves.

Now living life on the outside, Bernanke was also able to share a few reflections on his time in Washington, D.C., with the crowd. In such a partisan environment, he said, “Progress is sometimes frustratingly slow.”

“I testified before Congress 80 times,” Bernanke said. Even in the depths of the crisis, lawmakers weren’t always on his side.

With the lecture drawing to a close, Eberly asked how well Bernanke had adjusted back to his normal life.

Naming parking and airport security as newfound dilemmas, Bernanke also said he has some distance from governmental chaos.

“[It’s nice to say] that’s a serious problem. I hope somebody does something about that,” Bernanke said with a smile.

Perhaps due to small jokes like these, Carl Ge, a Weinberg freshman, said afterward that he was surprised to see Bernanke’s human side.

“Before I heard him [speak], I thought he was some kind of guy robot who knew everything about econ,” Ge said. “It was kinda nice to see how relatable it [his experience] was.”